Pacific wren

The Pacific wren (Troglodytes pacificus) is a very small North American bird and a member of the mainly New World wren family Troglodytidae. It was once lumped with Troglodytes hiemalis of eastern North America and Troglodytes troglodytes of Eurasia as the winter wren.

| Pacific wren | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Troglodytidae |

| Genus: | Troglodytes (?) |

| Subgenus: | Nannus |

| Species: | T. pacificus |

| Binomial name | |

| Troglodytes pacificus Baird, 1864 | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Nannus pacificus | |

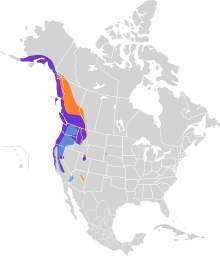

It breeds along the Pacific coast from Alaska to California and inland as far as Wyoming and the Black Hills of South Dakota. It migrates through and winters across the western half of the United States and Canada.

The scientific name is taken from the Greek word "troglodytes" (from "trogle" a hole, and "dyein" to creep), meaning "cave-dweller", and refers to its habit of disappearing into cavities or crevices whilst hunting arthropods or to roost.

Description

Rufous brown above, richly colored below, barred with darker brown and dusky, even on wings and tail. The bill is dark brown, the legs pale brown. Young birds are less distinctly barred.

Taxonomy

By studying the songs and genetics of individuals in an overlap zone between Troglodytes hiemalis and Troglodytes pacificus, Toews and Irwin (2008)[2] found strong evidence of reproductive isolation between the two. It was suggested that the pacificus subspecies be promoted to the species level designation of Troglodytes pacificus with the common name of ‘Pacific wren’. By applying a molecular clock to the amount of mitochondrial DNA sequence divergence between the two,[3] it was estimated that Troglodytes pacificus and Troglodytes troglodytes last shared a common ancestor approximately 4.3 million years ago, long before the glacial cycles of the Pleistocene, thought to have promoted speciation in many avian systems inhabiting the boreal forest of North America.[4]

Ecology

The Pacific wren nests mostly in coniferous forests, especially those of spruce and fir, where it is often identified by its long and exuberant song. Although it is an insectivore, it can remain in moderately cold and even snowy climates by foraging for insects on substrates such as bark and fallen logs.

Its movements as it creeps or climbs are incessant rather than rapid; its short flights swift and direct but not sustained, its tiny round wings whirring as it flies from bush to bush.

At night, usually in winter, it often roosts, true to its scientific name, in dark retreats, snug holes and even old nests. In hard weather it may do so in parties, either consisting of the family or of many individuals gathered together for warmth.

For the most part insects and spiders are its food, but in winter large pupae are taken and some seeds.

Breeding

The male builds a small number of nests. These are called "cock nests" but are never lined until the female chooses one to use.

The normal round nest of grass, moss, lichens or leaves is tucked into a hole in a wall, tree trunk, crack in a rock or corner of a building, but it is often built in bushes, overhanging boughs or the litter which accumulates in branches washed by floods.

Five to eight white or slightly speckled eggs are laid in April, and second broods are reared.

References

- "BirdLife International Species factsheet: Troglodytes troglodytes". BirdLife International. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- Toews, David P. L.; Darren E. Irwin (2008). "Cryptic speciation in a Holarctic passerine revealed by genetic and bioacoustic analyses". Molecular Ecology. 17 (11): 2691–2705. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03769.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 18444983.

- Drovetski, S. V.; R. M. Zink; S. Rohwer; I. V. Fadeev; E. V. Nesterov; I. Karagodin; E. A. Koblik; Y. A. Red'kin (2004). "Complex biogeographic history of a Holarctic passerine" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1538): 545–551. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2638. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1691619. PMID 15129966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-16.

- Weir, J. T.; D. Schluter (2004). "Ice sheets promote speciation in boreal birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1551): 1881–1887. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2803. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1691815. PMID 15347509.