Dura mater

Dura mater is a thick membrane made of dense irregular connective tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. It is the outermost of the three layers of membrane called the meninges that protect the central nervous system. The other two meningeal layers are the arachnoid mater and the pia mater. The dura surrounds the brain and the spinal cord. It envelops the arachnoid mater, which is responsible for keeping in the cerebrospinal fluid. It is derived primarily from the neural crest cell population, with postnatal contributions of the paraxial mesoderm.[1]

| Dura mater | |

|---|---|

Meninges of the CNS | |

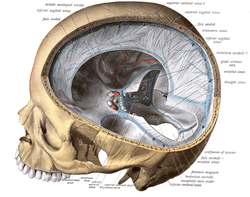

The dura mater extends into the skull cavity as the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli etc. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | UK: /ˈdjʊərə ˈmeɪtər/, US: /- ˈmætər/ |

| Precursor | Neural crest |

| Part of | Meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Dura mater |

| MeSH | D004388 |

| TA | A14.1.01.101 A14.1.01.002 |

| FMA | 9592 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The dura mater has several functions and layers. The dura mater is a membrane that envelops the arachnoid mater. It surrounds and supports the dural sinuses (also called dural venous sinuses, cerebral sinuses, or cranial sinuses) and carries blood from the brain toward the heart.

Cranial dura mater has two layers called lamellae, a superficial layer (also called the periosteal layer), which serves as the skull's inner periosteum, called the endocranium and a deep layer called the meningeal layer. When it covers the spinal cord it is known as the dural sac or thecal sac. Unlike cranial dura mater, spinal dura mater only has one layer, known as the meningeal layer. The potential space between these two layers is known as the epidural space.

Folds and reflections

The dura separates into two layers at dural reflections (also known as dural folds), places where the inner dural layer is reflected as sheet-like protrusions into the cranial cavity. There are two main dural reflections:

- The tentorium cerebelli exists between and separates the cerebellum and brainstem from the occipital lobes of the cerebrum.[2]

- The falx cerebri, which separates the two hemispheres of the brain, is located in the longitudinal cerebral fissure between the hemispheres.[3]

Two other dural infoldings are the cerebellar falx and the sellar diaphragm:

- The cerebellar falx (falx cerebelli) is a vertical dural infolding that lies inferior to the cerebellar tentorium in the posterior part of the posterior cranial fossa. It partially separates the cerebellar hemispheres.

- The sellar diaphragm is the smallest dural infolding and is a circular sheet of dura that is suspended between the clinoid processes, forming a partial roof over the hypophysial fossa. The sellar diaphgram covers the pituitary gland in this fossa and has an aperture for passage of the infundibulum (pituitary stalk) and hypophysial veins.

Blood supply

This depends upon the area of the cranial cavity: in the anterior cranial fossa the anterior meningeal artery (branch from the ethmoidal artery) is responsible for blood supply, in the middle cranial fossa the middle meningeal artery and some accessory arteries are responsible for blood supply, the middle meningeal artery is a direct branch from the maxillary artery and enter the cranial cavity through the foramen spinosum and then divides into anterior (which runs usually in vertical direction across the pterion) and posterior (which runs posteriosuperiorly) branches, while the accessory meningeal arteries (which are branches from the maxillary artery) enter the skull through foramen ovale and supply area between the two foramina, and the in posterior cranial fossa the dura mater has numerous blood supply from different possible arteries:

A. posterior meningeal artery (from the ascending pharyngeal artery through the jugular foramen)

B. meningeal arteries (from the ascending pharyngeal artery through hypoglossal canal)

C. meningeal arteries (from occipital artery through jugular or mastoid foramen)

D. meningeal arteries (from vertebral artery through foramen magnum)

Drainage

The two layers of dura mater run together throughout most of the skull. Where they separate, the gap between them is called a dural venous sinus. These sinuses drain blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain and empty into the internal jugular vein.

Arachnoid villi, which are outgrowths of the arachnoid mater (the middle meningeal layer), extend into the dural venous sinuses to drain CSF. These villi act as one-way valves. Meningeal veins, which course through the dura mater, and bridging veins, which drain the underlying neural tissue and puncture the dura mater, empty into these dural sinuses. A rupture of a bridging vein causes a subdural hematoma.

Nerve supply

The supratentorial dura mater membrane is supplied by small meningeal branches of the trigeminal nerve (V1, V2 and V3).[4] The innervation for the infratentorial dura mater are via upper cervical nerves and the meningeal branch of the vagus nerve.[5]

Clinical significance

Many medical conditions involve the dura mater. A subdural hematoma occurs when there is an abnormal collection of blood between the dura and the arachnoid, usually as a result of torn bridging veins secondary to head trauma. An epidural hematoma is a collection of blood between the dura and the inner surface of the skull, and is usually due to arterial bleeding. Intradural procedures, such as removal of a brain tumour, or treatment of trigeminal neuralgia via a microvascular decompression require that an incision is made to the dura mater. To achieve a watertight repair and avoid potential post-operative complications the dura is typically closed with sutures. In the event that there is a dural deficiency, a dural substitute may be used to replace this membrane. Small gaps in the dura can be covered with a surgical sealant film.

In 2011, researchers discovered a connective tissue bridge from the rectus capitis posterior major to the cervical dura mater. Various clinical manifestations may be linked to this anatomical relationship such as headaches, trigeminal neuralgia and other symptoms that involved the cervical dura.[6] The rectus capitis posterior minor has a similar attachment.[7]

The dura-muscular, dura-ligamentous connections in the upper cervical spine and occipital areas may provide anatomic and physiologic answers to the cause of the cervicogenic headache. This proposal would further explain manipulation's efficacy in the treatment of cervicogenic headache.[8]

The American Red Cross and some other agencies accepting blood donations consider dura mater transplants, along with receipt of pituitary-derived growth hormone, a risk factor due to concerns about Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[9]

Cerebellar tonsillar ectopia, or Chiari, is a condition that was previously thought to be congenital but can be induced by trauma, particularly whiplash trauma.[10] Dural strain may be pulling the cerebellum inferiorly, or skull distortions may be pushing the brain inferiorly.

Dural ectasia is the enlargement of the dura and is common in connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. These conditions are sometimes found in conjunction with Arnold–Chiari malformation.

Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak is the fluid and pressure loss of spinal fluid due to holes in the dura mater.

Etymology

The name dura mater derives from the Latin for tough mother (or hard mother) [11], a loan translation of Arabic أم الدماغ الصفيقة (umm al-dimāgh al-ṣafīqah), literally 'thick mother of the brain', matrix of the brain,[12][13] and is also referred to by the term "pachymeninx" (plural "pachymeninges").[12]

Additional images

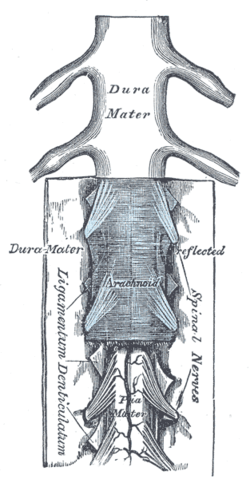

Dura mater (spinal section)

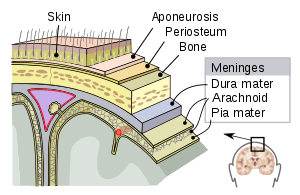

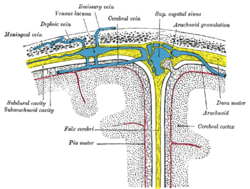

Dura mater (spinal section) Diagrammatic representation of a section across the top of the skull, showing the membranes of the brain, etc.

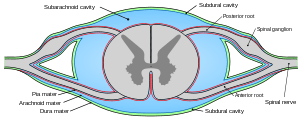

Diagrammatic representation of a section across the top of the skull, showing the membranes of the brain, etc. Diagrammatic transverse section of the medulla spinalis and its membranes.

Diagrammatic transverse section of the medulla spinalis and its membranes.- Spinal cord. Spinal membranes and nerve roots.Deep dissection. Posterior view.

- Spinal cord. Spinal membranes and nerve roots.Deep dissection. Posterior view

Autopsy. Dura mater is retracted by the forceps.

Autopsy. Dura mater is retracted by the forceps.

See also

References

- Gagan, Jeffrey R.; Tholpady, Sunil S.; Ogle, Roy C. (2007). "Cellular dynamics and tissue interactions of the dura mater during head development". Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 81 (4): 297–304. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20104. PMID 18228258.

- Shepherd S. 2004. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com.

- Vinas FC and Pilitsis J. 2004. "Penetrating Head Trauma." Emedicine.com.

- 'Gray's Anatomy for Students' 2005, Drake, Vogl and Mitchell, Elsevier

- Keller, Jeffrey T.; Saunders, Mary C.; Beduk, Altay; Jollis, James G. (1985-01-01). "Innervation of the posterior fossa dura of the cat". Brain Research Bulletin. 14 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(85)90181-9. ISSN 0361-9230. PMID 3872702.

- Frank Scali; Eric S. Marsili; Matt E. Pontell (2011). "Anatomical Connection Between the Rectus Capitis Posterior Major and the Dura Mater". Spine. 36 (25): E1612–E1614. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e31821129df. PMID 21278628. S2CID 31560001.

- Hack, GD (Dec 1, 1995). "Anatomic relation between the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle and the dura mater". Spine. 20 (23): 2484–6. doi:10.1097/00007632-199512000-00003. PMID 8610241.

- Gary D. Hack; Peter Ratiu; John P. Kerr; Gwendolyn F. Dunn; Mi Young Toh. "Visualization of the Muscle-Dural Bridge in the Visible Human Female Data Set". The Visible Human Project, National Library of Medicine.

- International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement - redcross.org

- Freeman, MD (2010). "A case-control study of cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (Chiari) and head/neck trauma (whiplash)". Brain Injury. 24 (7–8): 988–94. doi:10.3109/02699052.2010.490512. PMID 20545453.

- Sakka, Laurent (2019-12-17), "Anatomy of the Spinal Meninges", Spinal Anatomy, Springer International Publishing, pp. 403–419, ISBN 978-3-030-20924-7, retrieved 2020-06-08

- William C. Shiel Jr. "Medical Definition of Dura". Medicine Net.

- "dura mater (n.)". Etymonline. Douglas Harper.

External links

- youtube: exposure of falx cerebri, dura mater & arachnoid