PubMed

PubMed is a free search engine accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of Health maintain the database as part of the Entrez system of information retrieval.[1]

| |

|---|---|

| Contact | |

| Research center | United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) |

| Release date | January 1996 |

| Access | |

| Website | pubmed |

From 1971 to 1997, online access to the MEDLINE database had been primarily through institutional facilities, such as university libraries. PubMed, first released in January 1996, ushered in the era of private, free, home- and office-based MEDLINE searching.[2] The PubMed system was offered free to the public starting in June 1997.[3]

Content

In addition to MEDLINE, PubMed provides access to:

- older references from the print version of Index Medicus, back to 1951 and earlier

- references to some journals before they were indexed in Index Medicus and MEDLINE, for instance Science, BMJ, and Annals of Surgery

- very recent entries to records for an article before it is indexed with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and added to MEDLINE

- a collection of books available full-text and other subsets of NLM records [4]

- PMC citations

- NCBI Bookshelf

Many PubMed records contain links to full text articles, some of which are freely available, often in PubMed Central[5] and local mirrors, such as Europe PubMed Central.[6]

Information about the journals indexed in MEDLINE, and available through PubMed, is found in the NLM Catalog.[7]

As of 27 January 2020, PubMed has more than 30 million citations and abstracts dating back to 1966, selectively to the year 1865, and very selectively to 1809. As of the same date, 20 million of PubMed's records are listed with their abstracts, and 21.5 million records have links to full-text versions (of which 7.5 million articles are available, full-text for free).[8] Over the last 10 years (ending 31 December 2019), an average of nearly 1 million new records were added each year. Approximately 12% of the records in PubMed correspond to cancer-related entries, which have grown from 6% in the 1950s to 16% in 2016.[9] Other significant proportion of records correspond to "chemistry" (8.69%), "therapy" (8.39%), and "infection" (5%).

In 2016, NLM changed the indexing system so that publishers are able to directly correct typos and errors in PubMed indexed articles.[10]

PubMed has been reported to include some articles published in predatory journals. MEDLINE and PubMed policies for the selection of journals for database inclusion are slightly different. Weaknesses in the criteria and procedures for indexing journals in PubMed Central may allow publications from predatory journals to leak into PubMed.[11]

Characteristics

Website design

A new PubMed interface was launched in October 2009 and encouraged the use of such quick, Google-like search formulations; they have also been described as 'telegram' searches.[12] By default the results are sorted by Most Recent, but this can be changed to Best Match, Publication Date, First Author, Last Author, Journal, or Title.[13]

The PubMed website design and domain was updated in January 2020 and became default on May 15, 2020, with the updated and new features.[14] There was a critical reaction from many researchers who frequently use the site.[15]

PubMed for handhelds/mobiles

PubMed/MEDLINE can be accessed via handheld devices, using for instance the "PICO" option (for focused clinical questions) created by the NLM.[16] A "PubMed Mobile" option, providing access to a mobile friendly, simplified PubMed version, is also available.[17]

Search

Standard search

Simple searches on PubMed can be carried out by entering key aspects of a subject into PubMed's search window.

PubMed translates this initial search formulation and automatically adds field names, relevant MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms, synonyms, Boolean operators, and 'nests' the resulting terms appropriately, enhancing the search formulation significantly, in particular by routinely combining (using the OR operator) textwords and MeSH terms.

The examples given in a PubMed tutorial[18] demonstrate how this automatic process works:

Causes Sleep Walking is translated as ("etiology"[Subheading] OR "etiology"[All Fields] OR "causes"[All Fields] OR "causality"[MeSH Terms] OR "causality"[All Fields]) AND ("somnambulism"[MeSH Terms] OR "somnambulism"[All Fields] OR ("sleep"[All Fields] AND "walking"[All Fields]) OR "sleep walking"[All Fields])

Likewise,

soft Attack Aspirin Prevention is translated as ("myocardial infarction"[MeSH Terms] OR ("myocardial"[All Fields] AND "infarction"[All Fields]) OR "myocardial infarction"[All Fields] OR ("heart"[All Fields] AND "attack"[All Fields]) OR "heart attack"[All Fields]) AND ("aspirin"[MeSH Terms] OR "aspirin"[All Fields]) AND ("prevention and control"[Subheading] OR ("prevention"[All Fields] AND "control"[All Fields]) OR "prevention and control"[All Fields] OR "prevention"[All Fields])

Comprehensive search

For optimal searches in PubMed, it is necessary to understand its core component, MEDLINE, and especially of the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) controlled vocabulary used to index MEDLINE articles. They may also require complex search strategies, use of field names (tags), proper use of limits and other features; reference librarians and search specialists offer search services.[19][20]

The search into PubMed's search window is only recommended for the search of unequivocal topics or new interventions that do not yet have a MeSH heading created, as well as for the search for commercial brands of medicines and proper nouns. It is also useful when there is no suitable heading or the descriptor represents a partial aspect. The search using the thesaurus MeSH is more accurate and will give fewer irrelevant results. In addition, it saves the disadvantage of the free text search in which the spelling, singular/plural or abbreviated differences have to be taken into consideration. On the other side, articles more recently incorporated into the database to which descriptors have not yet been assigned will not be found. Therefore, to guarantee an exhaustive search, a combination of controlled language headings and free text terms must be used.[21]

Journal article parameters

When a journal article is indexed, numerous article parameters are extracted and stored as structured information. Such parameters are: Article Type (MeSH terms, e.g., "Clinical Trial"), Secondary identifiers, (MeSH terms), Language, Country of the Journal or publication history (e-publication date, print journal publication date).

Publication Type: Clinical queries/systematic reviews

Publication type parameter allows searching by the type of publication, including reports of various kinds of clinical research.[22]

Secondary ID

Since July 2005, the MEDLINE article indexing process extracts identifiers from the article abstract and puts those in a field called Secondary Identifier (SI). The secondary identifier field is to store accession numbers to various databases of molecular sequence data, gene expression or chemical compounds and clinical trial IDs. For clinical trials, PubMed extracts trial IDs for the two largest trial registries: ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT identifier) and the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register (IRCTN identifier).[23]

See also

A reference which is judged particularly relevant can be marked and "related articles" can be identified. If relevant, several studies can be selected and related articles to all of them can be generated (on PubMed or any of the other NCBI Entrez databases) using the 'Find related data' option. The related articles are then listed in order of "relatedness". To create these lists of related articles, PubMed compares words from the title and abstract of each citation, as well as the MeSH headings assigned, using a powerful word-weighted algorithm.[24] The 'related articles' function has been judged to be so precise that the authors of a paper suggested it can be used instead of a full search.[25]

Mapping to MeSH

PubMed automatically links to MeSH terms and subheadings. Examples would be: "bad breath" links to (and includes in the search) "halitosis", "heart attack" to "myocardial infarction", "breast cancer" to "breast neoplasms". Where appropriate, these MeSH terms are automatically "expanded", that is, include more specific terms. Terms like "nursing" are automatically linked to "Nursing [MeSH]" or "Nursing [Subheading]". This feature is called Auto Term Mapping and is enacted, by default, in free text searching but not exact phrase searching (i.e. enclosing the search query with double quotes).[26] This feature makes PubMed searches more sensitive and avoids false-negative (missed) hits by compensating for the diversity of medical terminology.[26]

PubMed does not apply automatic mapping of the term in the following circumstances: by writing the quoted phrase (e.g., "kidney allograft"), when truncated on the asterisk (e.g., kidney allograft*), and when looking with field labels (e.g., Cancer [ti]).[21]

My NCBI

The PubMed optional facility "My NCBI" (with free registration) provides tools for

- saving searches

- filtering search results

- setting up automatic updates sent by e-mail

- saving sets of references retrieved as part of a PubMed search

- configuring display formats or highlighting search terms

and a wide range of other options.[27] The "My NCBI" area can be accessed from any computer with web-access. An earlier version of "My NCBI" was called "PubMed Cubby".[28]

LinkOut

LinkOut, a NLM facility to link (and make available full-text) local journal holdings.[29] Some 3,200 sites (mainly academic institutions) participate in this NLM facility (as of March 2010), from Aalborg University in Denmark to ZymoGenetics in Seattle.[30] Users at these institutions see their institution's logo within the PubMed search result (if the journal is held at that institution) and can access the full-text. Link out is being consolidated with Outside Tool as of the major platform update coming in the Summer of 2019.[31]

PubMed Commons

In 2016, PubMed allows authors of articles to comment on articles indexed by PubMed. This feature was initially tested in a pilot mode (since 2013) and was made permanent in 2016.[32] In February 2018, PubMed Commons was discontinued due to the fact that "usage has remained minimal".[33][34]

askMEDLINE

askMEDLINE, a free-text, natural language query tool for MEDLINE/PubMed, developed by the NLM, also suitable for handhelds.[35]

PubMed identifier

A PMID (PubMed identifier or PubMed unique identifier)[36] is a unique integer value, starting at 1, assigned to each PubMed record. A PMID is not the same as a PMCID (PubMed Central identifier) which is the identifier for all works published in the free-to-access PubMed Central.[37]

The assignment of a PMID or PMCID to a publication tells the reader nothing about the type or quality of the content. PMIDs are assigned to letters to the editor, editorial opinions, op-ed columns, and any other piece that the editor chooses to include in the journal, as well as peer-reviewed papers. The existence of the identification number is also not proof that the papers have not been retracted for fraud, incompetence, or misconduct. The announcement about any corrections to original papers may be assigned a PMID.

Each number that is entered in the PubMed search window is treated by default as if it were a PMID. Therefore, any reference in PubMed can be located using the PMID.

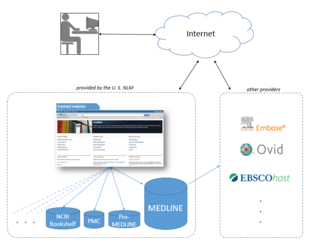

Alternative interfaces

The National Library of Medicine leases the MEDLINE information to a number of private vendors such as Embase, Ovid, Dialog, EBSCO, Knowledge Finder and many other commercial, non-commercial, and academic providers.[38] As of October 2008, more than 500 licenses had been issued, more than 200 of them to providers outside the United States. As licenses to use MEDLINE data are available for free, the NLM in effect provides a free testing ground for a wide range[39] of alternative interfaces and 3rd party additions to PubMed, one of a very few large, professionally curated databases which offers this option.

Lu[39] identifies a sample of 28 current and free Web-based PubMed versions, requiring no installation or registration, which are grouped into four categories:

- Ranking search results, for instance: eTBLAST; MedlineRanker;[40] MiSearch;[41]

- Clustering results by topics, authors, journals etc., for instance: Anne O'Tate;[42] ClusterMed;[43]

- Enhancing semantics and visualization, for instance: EBIMed;[44] MedEvi.[45]

- Improved search interface and retrieval experience, for instance, askMEDLINE[46][47] BabelMeSH;[48] and PubCrawler.[49]

As most of these and other alternatives rely essentially on PubMed/MEDLINE data leased under license from the NLM/PubMed, the term "PubMed derivatives" has been suggested.[39] Without the need to store about 90 GB of original PubMed Datasets, anybody can write PubMed applications using the eutils-application program interface as described in "The E-utilities In-Depth: Parameters, Syntax and More", by Eric Sayers, PhD.[50] Various citation format generators, taking PMID numbers as input, are examples of web applications making use of the eutils-application program interface. Sample web pages include Citation Generator - Mick Schroeder, Pubmed Citation Generator - Ultrasound of the Week, PMID2cite, and Cite this for me.

Data mining of PubMed

Alternative methods to mine the data in PubMed use programming environments such as Matlab, Python or R. In these cases, queries of PubMed are written as lines of code and passed to PubMed and the response is then processed directly in the programming environment. Code can be automated to systematically queries with different keywords such as disease, year, organs, etc. A recent publication (2017) found that the proportion of cancer-related entries in PubMed has risen from 6% in the 1950s to 16% in 2016.[9]

The data accessible by PubMed can be mirrored locally using an unofficial tool such as MEDOC.[51]

Millions of PubMed records augment various open data datasets about open access, like Unpaywall. Data analysis tools like Unpaywall Journals are used by libraries to assist with big deal cancellations: libraries can avoid subscriptions for materials already served by instant open access via open archives like PubMed Central.[52]

References

- "PubMed".

- "PubMed Celebrates its 10th Anniversary". Technical Bulletin. United States National Library of Medicine. 5 October 2006. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Lindberg DA (2000). "Internet access to the National Library of Medicine" (PDF). Effective Clinical Practice. 3 (5): 256–60. PMID 11185333. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013.

- "PubMed: MEDLINE Retrieval on the World Wide Web". Fact Sheet. United States National Library of Medicine. 7 June 2002. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Roberts RJ (January 2001). "PubMed Central: The GenBank of the published literature". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (2): 381–2. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..381R. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.2.381. PMC 33354. PMID 11209037.

- McEntyre JR, Ananiadou S, Andrews S, Black WJ, Boulderstone R, Buttery P, et al. (January 2011). "UKPMC: a full text article resource for the life sciences". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database issue): D58-65. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1063. PMC 3013671. PMID 21062818.

- "NLM Catalogue: Journals referenced in the NCBI Databases". NCBI. 2011.

- (Note: To see the current size of the database simply type "1800:2100[dp]" into the search bar at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ and click "search".)

- Reyes-Aldasoro CC (2017). "The proportion of cancer-related entries in PubMed has increased considerably; is cancer truly "The Emperor of All Maladies"?". PLOS One. 12 (3): e0173671. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1273671R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173671. PMC 5345838. PMID 28282418.

- "MEDLINE/PubMed Production Improvements Underway". NLM Technical Bulletin (411): e1. July–August 2016.

- Manca A, Moher D, Cugusi L, Dvir Z, Deriu F (September 2018). "How predatory journals leak into PubMed". CMAJ. 190 (35): E1042–E1045. doi:10.1503/cmaj.180154. PMC 6148641. PMID 30181150.

- Clarke J, Wentz R (September 2000). "Pragmatic approach is effective in evidence based health care". BMJ. 321 (7260): 566–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7260.566/a. PMC 1118450. PMID 10968827.

- Fatehi F, Gray LC, Wootton R (January 2014). "How to improve your PubMed/MEDLINE searches: 2. display settings, complex search queries and topic searching". Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 20 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1177/1357633X13517067. PMID 24352897.

- Trawick, Bart (21 January 2020). "A New and Improved PubMed®". NLM Musings From the Mezzanine.

- Price, Michael (22 May 2020). "They redesigned PubMed, a beloved website. It hasn't gone over well". Science.

- "PubMed via handhelds (PICO)". Technical Bulletin. United States National Library of Medicine. 2004.

- "PubMed Mobile Beta". Technical Bulletin. United States National Library of Medicine. 2011.

- "Simple Subject Search with Quiz". NCBI. 2010.

- Jadad AR, McQuay HJ (July 1993). "Searching the literature. Be systematic in your searching". BMJ. 307 (6895): 66. doi:10.1136/bmj.307.6895.66-a. PMC 1678459. PMID 8343701.

- Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Weissman NW, Carter J, Centor RM (Spring 1999). "The art and science of searching MEDLINE to answer clinical questions. Finding the right number of articles". International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 15 (2): 281–96. doi:10.1017/S0266462399015214. PMID 10507188.

- Campos-Asensio C (2018). "Cómo elaborar una estrategia de búsqueda bibliográfica". Enfermería Intensiva (in Spanish). 29 (4): 182–186. doi:10.1016/j.enfi.2018.09.001. PMID 30291015.

- Clinical Queries Filter Terms explained. NCBI. 2010.

- Huser V, Cimino JJ (June 2013). "Evaluating adherence to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors' policy of mandatory, timely clinical trial registration". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 20 (e1): e169-74. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001501. PMC 3715364. PMID 23396544.

- "Computation of Related Articles explained". NCBI.

- Chang AA, Heskett KM, Davidson TM (February 2006). "Searching the literature using medical subject headings versus text word with PubMed". The Laryngoscope. 116 (2): 336–40. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000195371.72887.a2. PMID 16467730.

- Fatehi F, Gray LC, Wootton R (March 2014). "How to improve your PubMed/MEDLINE searches: 3. advanced searching, MeSH and My NCBI". Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 20 (2): 102–12. doi:10.1177/1357633X13519036. PMID 24614997.

- My NCBI explained. NCBI. 13 December 2010.

- "PubMed Cubby". Technical Bulletin. United States National Library of Medicine. 2000.

- "LinkOut Overview". NCBI. 2010.

- "LinkOut Participants 2011". NCBI. 2011.

- "An Updated PubMed is on its Way".

- PubMed Commons Team (17 December 2015). "Commenting on PubMed: A Successful Pilot".

- "PubMed Commons to be Discontinued". NCBI Insights. 1 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "PubMed shuts down its comments feature, PubMed Commons". Retraction Watch. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "askMedline". NCBI. 2005.

- "Search Field Descriptions and Tags". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Keener M. "PMID vs. PMCID: What's the difference?" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- "Leasing journal citations from PubMed/Medline". NLM. 2011.

- Lu Z (2011). "PubMed and beyond: a survey of web tools for searching biomedical literature". Database. 2011: baq036. doi:10.1093/database/baq036. PMC 3025693. PMID 21245076.

- Fontaine JF, Barbosa-Silva A, Schaefer M, Huska MR, Muro EM, Andrade-Navarro MA (July 2009). "MedlineRanker: flexible ranking of biomedical literature". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (Web Server issue): W141-6. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp353. PMC 2703945. PMID 19429696.

- States DJ, Ade AS, Wright ZC, Bookvich AV, Athey BD (April 2009). "MiSearch adaptive pubMed search tool". Bioinformatics. 25 (7): 974–6. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn033. PMC 2660869. PMID 18326507.

- Smalheiser NR, Zhou W, Torvik VI (February 2008). "Anne O'Tate: A tool to support user-driven summarization, drill-down and browsing of PubMed search results". Journal of Biomedical Discovery and Collaboration. 3: 2. doi:10.1186/1747-5333-3-2. PMC 2276193. PMID 18279519.

- "ClusterMed". Vivisimo Clustering Engine. 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- Rebholz-Schuhmann D, Kirsch H, Arregui M, Gaudan S, Riethoven M, Stoehr P (January 2007). "EBIMed--text crunching to gather facts for proteins from Medline". Bioinformatics. 23 (2): e237-44. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl302. PMID 17237098.

- Kim JJ, Pezik P, Rebholz-Schuhmann D (June 2008). "MedEvi: retrieving textual evidence of relations between biomedical concepts from Medline". Bioinformatics. 24 (11): 1410–2. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn117. PMC 2387223. PMID 18400773.

- Fontelo P, Liu F, Ackerman M, Schardt CM, Keitz SA (2006). "askMEDLINE: a report on a year-long experience". AMIA ... Annual Symposium Proceedings. AMIA Symposium. 2006: 923. PMC 1839379. PMID 17238542.

- Fontelo P, Liu F, Ackerman M (2005). "MeSH Speller + askMEDLINE: auto-completes MeSH terms then searches MEDLINE/PubMed via free-text, natural language queries". AMIA ... Annual Symposium Proceedings. AMIA Symposium. 2005: 957. PMC 1513542. PMID 16779244.

- Fontelo P, Liu F, Leon S, Anne A, Ackerman M (2007). "PICO Linguist and BabelMeSH: development and partial evaluation of evidence-based multilanguage search tools for MEDLINE/PubMed". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 129 (Pt 1): 817–21. PMID 17911830.

- Hokamp K, Wolfe KH (July 2004). "PubCrawler: keeping up comfortably with PubMed and GenBank". Nucleic Acids Research. 32 (Web Server issue): W16-9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh453. PMC 441591. PMID 15215341.

- Eric Sayers, PhD (24 October 2018). The E-utilities In-Depth: Parameters, Syntax and More. NCBI.

- "MEDOC (MEdline DOwnloading Contrivance)". 2017.

- Denise Wolfe (7 April 2020). "SUNY Negotiates New, Modified Agreement with Elsevier - Libraries News Center University at Buffalo Libraries". library.buffalo.edu. University at Buffalo. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

External links

Wikidata has the property:

|

- Official website

- PubMed legacy, the previous interface