Impact factor

The impact factor (IF) or journal impact factor (JIF) of an academic journal is a scientometric index that reflects the yearly average number of citations that articles published in the last two years in a given journal received. It is frequently used as a proxy for the relative importance of a journal within its field; journals with higher impact factors are often deemed to be more important than those with lower ones.

History

The impact factor was devised by Eugene Garfield, the founder of the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI). Impact factors are calculated yearly starting from 1975 for journals listed in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR). ISI was acquired by Thomson Scientific & Healthcare in 1992,[1] and became known as Thomson ISI. In 2018, Thomson ISI was sold to Onex Corporation and Baring Private Equity Asia.[2] They founded a new corporation, Clarivate, which is now the publisher of the JCR.[3]

Calculation

In any given year, the two-year journal impact factor is the ratio between the number of citations received in that year divided by the total number of "citable items" published in that journal during the two preceding years:[4][5]

For example, Nature had an impact factor of 41.577 in 2017:[6]

This means that, on average, its papers published in 2015 and 2016 received roughly 42 citations each in 2017. Note that 2017 impact factors are reported in 2018; they cannot be calculated until all of the 2017 publications have been processed by the indexing agency.

The value of impact factor depends on how to define "citations" and "publications"; the latter are often referred to as "citable items". In current practice, both "citations" and "publications" are defined exclusively by ISI as follows. "Publications" are items that are classed as "article", "review" or "proceedings paper"[7] in the Web of Science (WoS) database; other items like editorials, corrections, notes, retractions and discussions are excluded. WoS is accessible to all registered users, who can independently verify the number of citable items for a given journal. In contrast, the number of citations is extracted not from the WoS database, but from a dedicated JCR database, which is not accessible to general readers. Hence, the commonly used "JCR Impact Factor" is a proprietary value, which is defined and calculated by ISI and can not be verified by external users.[8]

New journals, which are indexed from their first published issue, will receive an impact factor after two years of indexing; in this case, the citations to the year prior to Volume 1, and the number of articles published in the year prior to Volume 1, are known zero values. Journals that are indexed starting with a volume other than the first volume will not get an impact factor until they have been indexed for three years. Occasionally, Journal Citation Reports assigns an impact factor to new journals with less than two years of indexing, based on partial citation data.[9][10] The calculation always uses two complete and known years of item counts, but for new titles one of the known counts is zero. Annuals and other irregular publications sometimes publish no items in a particular year, affecting the count. The impact factor relates to a specific time period; it is possible to calculate it for any desired period. For example, the JCR also includes a five-year impact factor, which is calculated by dividing the number of citations to the journal in a given year by the number of articles published in that journal in the previous five years.[11][12]

Use

The impact factor is used to compare different journals within a certain field. The Web of Science indexes more than 11,500 science and social science journals.[13]

Journal impact factors are often used to evaluate the merit of individual articles and individual researchers.[14] This use of impact factors was summarised by Hoeffel:[15]

Impact Factor is not a perfect tool to measure the quality of articles but there is nothing better and it has the advantage of already being in existence and is, therefore, a good technique for scientific evaluation. Experience has shown that in each specialty the best journals are those in which it is most difficult to have an article accepted, and these are the journals that have a high impact factor. Most of these journals existed long before the impact factor was devised. The use of impact factor as a measure of quality is widespread because it fits well with the opinion we have in each field of the best journals in our specialty....In conclusion, prestigious journals publish papers of high level. Therefore, their impact factor is high, and not the contrary.

As impact factors are a journal-level metric, rather than an article- or individual-level metric, this use is controversial. Garfield agrees with Hoeffel,[16] but warns about the "misuse in evaluating individuals" because there is "a wide variation [of citations] from article to article within a single journal".[17]

Criticism

Numerous critiques have been made regarding the use of impact factors.[18][19][20] A 2007 study noted that the most fundamental flaw is that impact factors present the mean of data that is not normally distributed, and suggested that it would be more appropriate to present the median of these data.[21] There is also a more general debate on the validity of the impact factor as a measure of journal importance and the effect of policies that editors may adopt to boost their impact factor (perhaps to the detriment of readers and writers). Other criticism focuses on the effect of the impact factor on behavior of scholars, editors and other stakeholders.[22] Others have made more general criticisms, arguing that emphasis on impact factor results from negative influence of neoliberal policies on academia claiming that what is needed is not just replacement of the impact factor with more sophisticated metrics for science publications but also discussion on the social value of research assessment and the growing precariousness of scientific careers in higher education.[23][24]

Validity as a measure of importance

It has been stated that impact factors and citation analysis in general are affected by field-dependent factors[25] which may invalidate comparisons not only across disciplines but even within different fields of research of one discipline.[26] The percentage of total citations occurring in the first two years after publication also varies highly among disciplines from 1–3% in the mathematical and physical sciences to 5–8% in the biological sciences.[27] Thus impact factors cannot be used to compare journals across disciplines.

Impact factors are sometimes used to evaluate not only the journals but the papers therein, thereby devaluing papers in certain subjects.[28] The Higher Education Funding Council for England was urged by the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee to remind Research Assessment Exercise panels that they are obliged to assess the quality of the content of individual articles, not the reputation of the journal in which they are published.[29] The effect of outliers can be seen in the case of the article "A short history of SHELX", which included this sentence: "This paper could serve as a general literature citation when one or more of the open-source SHELX programs (and the Bruker AXS version SHELXTL) are employed in the course of a crystal-structure determination". This article received more than 6,600 citations. As a consequence, the impact factor of the journal Acta Crystallographica Section A rose from 2.051 in 2008 to 49.926 in 2009, more than Nature (at 31.434) and Science (at 28.103).[30] The second-most cited article in Acta Crystallographica Section A in 2008 only had 28 citations.[31] Additionally, impact factor is a journal metric and should not be used to assess individual researchers or institutions.[32][33]

Journal rankings constructed based solely on impact factors only moderately correlate with those compiled from the results of expert surveys.[34]

A.E. Cawkell, former Director of Research at the Institute for Scientific Information remarked that the Science Citation Index (SCI), on which the impact factor is based, "would work perfectly if every author meticulously cited only the earlier work related to his theme; if it covered every scientific journal published anywhere in the world; and if it were free from economic constraints."[35]

Editorial policies that affect the impact factor

A journal can adopt editorial policies to increase its impact factor.[36][37] For example, journals may publish a larger percentage of review articles which generally are cited more than research reports.[5]

Journals may also attempt to limit the number of "citable items"—i.e., the denominator of the impact factor equation—either by declining to publish articles that are unlikely to be cited (such as case reports in medical journals) or by altering articles (e.g., by not allowing an abstract or bibliography in hopes that Journal Citation Reports will not deem it a "citable item"). As a result of negotiations over whether items are "citable", impact factor variations of more than 300% have been observed.[38] Items considered to be uncitable—and thus are not incorporated in impact factor calculations—can, if cited, still enter into the numerator part of the equation despite the ease with which such citations could be excluded. This effect is hard to evaluate, for the distinction between editorial comment and short original articles is not always obvious. For example, letters to the editor may refer to either class.

Another less insidious tactic journals employ is to publish a large portion of its papers, or at least the papers expected to be highly cited, early in the calendar year. This gives those papers more time to gather citations. Several methods, not necessarily with nefarious intent, exist for a journal to cite articles in the same journal which will increase the journal's impact factor.[39][40]

Beyond editorial policies that may skew the impact factor, journals can take overt steps to game the system. For example, in 2007, the specialist journal Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, with an impact factor of 0.66, published an editorial that cited all its articles from 2005 to 2006 in a protest against the "absurd scientific situation in some countries" related to use of the impact factor.[41] The large number of citations meant that the impact factor for that journal increased to 1.44. As a result of the increase, the journal was not included in the 2008 and 2009 Journal Citation Reports.[42]

Coercive citation is a practice in which an editor forces an author to add extraneous citations to an article before the journal will agree to publish it, in order to inflate the journal's impact factor. A survey published in 2012 indicates that coercive citation has been experienced by one in five researchers working in economics, sociology, psychology, and multiple business disciplines, and it is more common in business and in journals with a lower impact factor.[43] However, cases of coercive citation have occasionally been reported for other disciplines.[44]

Correlation between impact factor and quality

The journal impact factor (JIF) was originally designed by Eugene Garfield as a metric to help librarians make decisions about which journals were worth subscribing to, as the JIF aggregates the number of citations to articles published in each journal. Since then, the JIF has become associated as a mark of journal "quality", and gained widespread use for evaluation of research and researchers instead, even at the institutional level. It thus has significant impact on steering research practices and behaviours.[45][46]

Already around 2010, national and international research funding institutions have pointed out that numerical indicators such as the JIF should not be referred to as a measure of quality.[note 1] In fact, the JIF is a highly manipulated metric,[47][48][49] and the justification for its continued widespread use beyond its original narrow purpose seems due to its simplicity (easily calculable and comparable number), rather than any actual relationship to research quality.[50][51][52]

Empirical evidence shows that the misuse of the JIF – and journal ranking metrics in general – has a number of negative consequences for the scholarly communication system. These include confusion between outreach of a journal and the quality of individual papers and insufficient coverage of social sciences and humanities as well as research outputs from across Latin America, Africa, and South-East Asia.[53] Additional drawbacks include the marginalization of research in vernacular languages and on locally relevant topics, inducement to unethical authorship and citation practices as well as more generally fostering of a reputation economy in academia based on publishers" prestige rather than actual research qualities such as rigorous methods, replicability and social impact. Using journal prestige and the JIF to cultivate a competition regime in academia has been shown to have deleterious effects on research quality.[54]

JIFs are still regularly used to evaluate research in many countries which is a problem since a number of outstanding issues remain around the opacity of the metric and the fact that it is often negotiated by publishers.[55][56][57] However, these integrity problems appear to have done little to curb its widespread mis-use.

A number of regional focal points and initiatives are now providing and suggesting alternative research assessment systems, including key documents such as the Leiden Manifesto[note 2] and the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA). Recent developments around 'Plan S' call on a broader adoption and implementation of such initiatives alongside fundamental changes in the scholarly communication system.[note 3] Thus, there is little basis for the popular simplification which connects JIFs with any measure of quality, and the ongoing inappropriate association of the two will continue to have deleterious effects. As appropriate measures of quality for authors and research, concepts of research excellence should be remodelled around transparent workflows and accessible research results.[58][59][60]

Negotiated values

The method of calculation of the impact factor by Clarivate is not generally known and the results are therefore not predictable nor reproducible. In particular, the result can change dramatically depending on which items are considered as "citable" and therefore included in the denominator.[61] Publishers routinely discuss with Clarivate how to improve the "accuracy" of their journals' impact factor and therefore get higher scores.[62]

Such discussions routinely produce "negotiated values" which result in dramatic changes in the observed scores for dozens of journals, sometimes after unrelated events like the purchase by one of the big five publishers.[63]

Distribution skewness

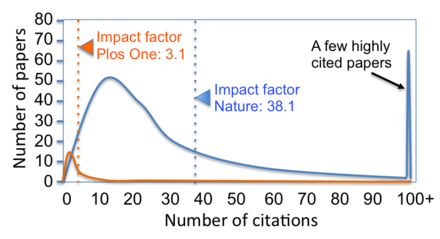

Because citation counts have highly skewed distributions,[65] the mean number of citations is potentially misleading if used to gauge the typical impact of articles in the journal rather than the overall impact of the journal itself.[66] For example, about 90% of Nature's 2004 impact factor was based on only a quarter of its publications, and thus the actual number of citations for a single article in the journal is in most cases much lower than the mean number of citations across articles.[67] Furthermore, the strength of the relationship between impact factors of journals and the citation rates of the papers therein has been steadily decreasing since articles began to be available digitally.[68]

Critics of the JIF state that use of the arithmetic mean in its calculation is problematic because the pattern of citation distribution is skewed. Citation distributions for eight selected journals in,[69] along with their JIFs and the percentage of citable items below the JIF shows that the distributions are clearly skewed, making the arithmetic mean an inappropriate statistic to use to say anything about individual papers within the citation distributions. More informative and readily available article-level metrics can be used instead, such as citation counts or "altmetrics', along with other qualitative and quantitative measures of research "impact'.[60][70]

Université de Montréal, Imperial College London, PLOS, eLife, EMBO Journal, The Royal Society, Nature and Science proposed citation distributions metrics as alternative to impact factors.[71][72][73]

Responses

Because "the impact factor is not always a reliable instrument", in November 2007 the European Association of Science Editors (EASE) issued an official statement recommending "that journal impact factors are used only—and cautiously—for measuring and comparing the influence of entire journals, but not for the assessment of single papers, and certainly not for the assessment of researchers or research programmes".[19]

In July 2008, the International Council for Science (ICSU) Committee on Freedom and Responsibility in the Conduct of Science (CFRS) issued a "statement on publication practices and indices and the role of peer review in research assessment", suggesting many possible solutions—e.g., considering a limit number of publications per year to be taken into consideration for each scientist, or even penalising scientists for an excessive number of publications per year—e.g., more than 20.[74]

In February 2010, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) published new guidelines to evaluate only articles and no bibliometric information on candidates to be evaluated in all decisions concerning "performance-based funding allocations, postdoctoral qualifications, appointments, or reviewing funding proposals, [where] increasing importance has been given to numerical indicators such as the h-index and the impact factor".[75] This decision follows similar ones of the National Science Foundation (US) and the Research Assessment Exercise (UK).

In response to growing concerns over the inappropriate use of journal impact factors in evaluating scientific outputs and scientists themselves, the American Society for Cell Biology together with a group of editors and publishers of scholarly journals created the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA). Released in May 2013, DORA has garnered support from thousands of individuals and hundreds of institutions,[24] including in March 2015 the League of European Research Universities (a consortium of 21 of the most renowned research universities in Europe),[76] who have endorsed the document on the DORA website.

Closely related indices

Some related values, also calculated and published by the same organization, include:

- Cited half-life: the median age of the articles that were cited in Journal Citation Reports each year. For example, if a journal's half-life in 2005 is 5, that means the citations from 2001–2005 are half of all the citations from that journal in 2005, and the other half of the citations precede 2001.[77]

- Aggregate impact factor for a subject category: it is calculated taking into account the number of citations to all journals in the subject category and the number of articles from all the journals in the subject category.

- Immediacy index: the number of citations the articles in a journal receive in a given year divided by the number of articles published.

As with the impact factor, there are some nuances to this: for example, ISI excludes certain article types (such as news items, correspondence, and errata) from the denominator.[78][79][80] [81]

Other measures of impact

Additional journal-level metrics are available from other organizations. For example, CiteScore: is a metric for serial titles in Scopus launched in December 2016 by Elsevier.[82][83] While these metrics apply only to journals, there are also author-level metrics, such as the H-index, that apply to individual researchers. In addition, article-level metrics measure impact at an article level instead of journal level. Other more general alternative metrics, or "altmetrics", may include article views, downloads, or mentions in social media.

Counterfeit

Fake impact factors or bogus impact factors are produced by companies or individuals not affiliated with the Journal Citation Reports (JCR).[84] According to an article published in the United States National Library of Medicine, these include Global Impact Factor (GIF), Citefactor, and Universal Impact Factor (UIF).[85] Jeffrey Beall maintained a list of such misleading metrics.[86][87] Another deceitful practice is reporting "alternative impact factors", calculated as the average number of citations per article using citation indices other than JCR, even if based on reputable sources such as Google Scholar (e.g., "Google-based Journal Impact Factor").[88]

False impact factors are often used by predatory publishers.[89] Consulting Journal Citation Reports' master journal list can confirm if a publication is indexed by Journal Citation Reports.[90] The use of fake impact metrics is considered a "red flag".[91]

See also

Notes

- ""Quality not Quantity" – DFG Adopts Rules to Counter the Flood of Publications in Research".. DFG Press Release No. 7 (2010)

- "The Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics". 2015.

- "Plan S implementation guidelines"., February 2019.

References

- "Thomson Corporation acquired ISI". Online. July 1992. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Acquisition of the Thomson Reuters Intellectual Property and Science Business by Onex and Baring Asia Completed".

- "Journal Citation Reports". Web of Science Group. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "Web of Science Group". Web of Science Group. 6 August 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Garfield, Eugene (20 June 1994). "The Thomson Reuters Impact Factor". Thomson Reuters. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Nature". 2017 Journal Citation Reports. Web of Science (Science ed.). Thomson Reuters. 2018.

- McVeigh, M. E.; Mann, S. J. (2009). "The Journal Impact Factor Denominator". JAMA. 302 (10): 1107–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1301. PMID 19738096.

- Hubbard, S. C.; McVeigh, M. E. (2011). "Casting a wide net: The Journal Impact Factor numerator". Learned Publishing. 24 (2): 133–137. doi:10.1087/20110208.

- "RSC Advances receives its first partial impact factor". RSC Advances Blog. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Our first (partial) impact factor and our continuing (full) story". news.cell.com. 30 July 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- "JCR with Eigenfactor". Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- "ISI 5-Year Impact Factor". APA. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "Every journal has a story to tell". Journal Citation Reports. Clarivate Analytics. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- McKiernan, Erin C; Schimanski, Lesley A; Muñoz Nieves, Carol; Matthias, Lisa; Niles, Meredith T; Alperin, Juan P (31 July 2019). "Use of the Journal Impact Factor in academic review, promotion, and tenure evaluations". eLife. 8. doi:10.7554/eLife.47338. PMC 6668985. PMID 31364991.

- Hoeffel, C. (1998). "Journal impact factors". Allergy. 53 (12): 1225. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb03848.x. PMID 9930604.

- Garfield, Eugene (2006). "The History and Meaning of the Journal Impact Factor" (PDF). JAMA. 295 (1): 90–3. Bibcode:2006JAMA..295...90G. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.90. PMID 16391221.

- Garfield, Eugene (June 1998). "The Impact Factor and Using It Correctly". Der Unfallchirurg. 101 (6): 413–414. PMID 9677838.

- "Time to remodel the journal impact factor". Nature. 535 (466): 466. 2016. Bibcode:2016Natur.535..466.. doi:10.1038/535466a. PMID 27466089.

- "European Association of Science Editors (EASE) Statement on Inappropriate Use of Impact Factors". Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Callaway, Ewen (2016). "Beat it, impact factor! Publishing elite turns against controversial metric". Nature. 535 (7611): 210–211. Bibcode:2016Natur.535..210C. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.20224. PMID 27411614.

- Rossner, M.; Van Epps, H.; Hill, E. (17 December 2007). "Show me the data". Journal of Cell Biology. 179 (6): 1091–2. doi:10.1083/jcb.200711140. PMC 2140038. PMID 18086910.

- Wesel, M. van (2016). "Evaluation by Citation: Trends in Publication Behavior, Evaluation Criteria, and the Strive for High Impact Publications". Science and Engineering Ethics. 22 (1): 199–225. doi:10.1007/s11948-015-9638-0. PMC 4750571. PMID 25742806.

- Kansa, Eric (27 January 2014). "It's the Neoliberalism, Stupid: Why instrumentalist arguments for Open Access, Open Data, and Open Science are not enough". LSE Impact Blog. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Cabello, F.; Rascón, M.T. (2015). "The Index and the Moon. Mortgaging Scientific Evaluation". International Journal of Communication. 9: 1880–1887.

- Bornmann, L.; Daniel, H. D. (2008). "What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior". Journal of Documentation. 64 (1): 45–80. doi:10.1108/00220410810844150.

- Anauati, Maria Victoria; Galiani, Sebastian; Gálvez, Ramiro H. (11 November 2014). "Quantifying the Life Cycle of Scholarly Articles Across Fields of Economic Research". SSRN 2523078. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - van Nierop, Erjen (2009). "Why Do Statistics Journals Have Low Impact Factors?". Statistica Neerlandica. 63 (1): 52–62. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9574.2008.00408.x.

- Bohannon, John (2016). "Hate journal impact factors? New study gives you one more reason". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aag0643.

- "House of Commons – Science and Technology – Tenth Report". 7 July 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- Grant, Bob (21 June 2010). "New impact factors yield surprises". The Scientist. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- mmcveigh (17 June 2010). "What does it mean to be #2 in Impact?". Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Seglen, P. O. (1997). "Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research". BMJ. 314 (7079): 498–502. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7079.497. PMC 2126010. PMID 9056804.

- "EASE Statement on Inappropriate Use of Impact Factors". European Association of Science Editors. November 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Serenko, A.; Dohan, M. (2011). "Comparing the expert survey and citation impact journal ranking methods: Example from the field of Artificial Intelligence" (PDF). Journal of Informetrics. 5 (4): 629–648. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2011.06.002.

- Cawkell, Anthony E. (1977). "Science perceived through the Science Citation Index". Endeavour. 1 (2): 57–62. doi:10.1016/0160-9327(77)90107-7. PMID 71986.

- Monastersky, Richard (14 October 2005). "The Number That's Devouring Science". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Arnold, Douglas N.; Fowler, Kristine K. (2011). "Nefarious Numbers". Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 58 (3): 434–437. arXiv:1010.0278. Bibcode:2010arXiv1010.0278A.

- PLoS Medicine Editors (6 June 2006). "The Impact Factor Game". PLOS Medicine. 3 (6): e291. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030291. PMC 1475651. PMID 16749869.

- Agrawal, A. (2005). "Corruption of Journal Impact Factors" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 20 (4): 157. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.002. PMID 16701362. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2010.

- Fassoulaki, A.; Papilas, K.; Paraskeva, A.; Patris, K. (2002). "Impact factor bias and proposed adjustments for its determination". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 46 (7): 902–5. doi:10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460723.x. PMID 12139549.

- Schuttea, H. K.; Svec, J. G. (2007). "Reaction of Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica on the Current Trend of Impact Factor Measures". Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 59 (6): 281–285. doi:10.1159/000108334. PMID 17965570.

- "Journal Citation Reports – Notices". Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Wilhite, A. W.; Fong, E. A. (2012). "Coercive Citation in Academic Publishing". Science. 335 (6068): 542–3. Bibcode:2012Sci...335..542W. doi:10.1126/science.1212540. PMID 22301307.

- Smith, Richard (1997). "Journal accused of manipulating impact factor". BMJ. 314 (7079): 463. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7079.461d. PMC 2125988. PMID 9056791.

- Gargouri, Yassine; Hajjem, Chawki; Lariviere, Vincent; Gingras, Yves; Carr, Les; Brody, Tim; Harnad, Stevan (2018). "The Journal Impact Factor: A Brief History, Critique, and Discussion of Adverse Effects". arXiv:1801.08992. Bibcode:2018arXiv180108992L. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Curry, Stephen (2018). "Let's Move beyond the Rhetoric: It's Time to Change How We Judge Research". Nature. 554 (7691): 147. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..147C. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-01642-w. PMID 29420505.

- Falagas, Matthew E.; Alexiou, Vangelis G. (2008). "The Top-Ten in Journal Impact Factor Manipulation". Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 56 (4): 223–226. doi:10.1007/s00005-008-0024-5. PMID 18661263.

- Tort, Adriano B. L.; Targino, Zé H.; Amaral, Olavo B. (2012). "Rising Publication Delays Inflate Journal Impact Factors". PLOS One. 7 (12): e53374. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...753374T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053374. PMC 3534064. PMID 23300920.

- Fong, Eric A.; Wilhite, Allen W. (2017). "Authorship and Citation Manipulation in Academic Research". PLOS One. 12 (12): e0187394. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1287394F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187394. PMC 5718422. PMID 29211744.

- "Citation Statistics". A Report from the Joint.

- Brembs, B. (2018). "Prestigious Science Journals Struggle to Reach Even Average Reliability". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 12: 37. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00037. PMC 5826185. PMID 29515380.

- Gargouri, Yassine; Hajjem, Chawki; Lariviere, Vincent; Gingras, Yves; Carr, Les; Brody, Tim; Harnad, Stevan (2009). "The Impact Factor's Matthew Effect: A Natural Experiment in Bibliometrics". arXiv:0908.3177. Bibcode:2009arXiv0908.3177L. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Brembs, Björn; Button, Katherine; Munafò, Marcus (2013). "Deep impact: Unintended consequences of journal rank". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 7: 291. arXiv:1301.3748. Bibcode:2013arXiv1301.3748B. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00291. PMC 3690355. PMID 23805088.

- Vessuri, Hebe; Guédon, Jean-Claude; Cetto, Ana María (2014). "Excellence or Quality? Impact of the Current Competition Regime on Science and Scientific Publishing in Latin America and Its Implications for Development" (PDF). Current Sociology. 62 (5): 647–665. doi:10.1177/0011392113512839.

- "Open Access and the Divide between 'Mainstream" and "peripheral". Como Gerir e Qualificar Revistas Científicas: 1–25.

- McKiernan, Erin C.; Niles, Meredith T.; Fischman, Gustavo E.; Schimanski, Lesley; Nieves, Carol Muñoz; Alperin, Juan Pablo (2019). "How Significant Are the Public Dimensions of Faculty Work in Review, Promotion, and Tenure Documents?". eLife. 8. doi:10.7554/eLife.42254. PMC 6391063. PMID 30747708.

- Rossner, Mike; Van Epps, Heather; Hill, Emma (2007). "Show Me the Data". The Journal of Cell Biology. 179 (6): 1091–1092. doi:10.1083/jcb.200711140. PMC 2140038. PMID 18086910.

- Moore, Samuel; Neylon, Cameron; Paul Eve, Martin; Paul o'Donnell, Daniel; Pattinson, Damian (2017). "'Excellence R Us': University Research and the Fetishisation of Excellence". Palgrave Communications. 3. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2016.105.

- Owen, R.; MacNaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. (2012). "Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society". Science and Public Policy. 39 (6): 751–760. doi:10.1093/scipol/scs093.

- Hicks, Diana; Wouters, Paul; Waltman, Ludo; De Rijcke, Sarah; Rafols, Ismael (2015). "Bibliometrics: The Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics". Nature. 520 (7548): 429–431. Bibcode:2015Natur.520..429H. doi:10.1038/520429a. PMID 25903611.

- Adam, David. "The counting house". Nature. 415 (6873): 726–729. doi:10.1038/415726a.

- The PLoS Medicine Editors (6 June 2006). "The Impact Factor Game". PLoS Medicine. 3 (6): e291. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030291. PMC 1475651. PMID 16749869.

- Björn Brembs (8 January 2016). "Just how widespread are impact factor negotiations?". Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Callaway, E. (2016). "Beat it, impact factor! Publishing elite turns against controversial metric". Nature. 535 (7611): 210–211. Bibcode:2016Natur.535..210C. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.20224. PMID 27411614.

- Callaway, Ewen (14 July 2016). "Beat it, impact factor! Publishing elite turns against controversial metric". Nature. 535 (7611): 210–211. Bibcode:2016Natur.535..210C. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.20224. PMID 27411614.

- Joint Committee on Quantitative Assessment of Research (12 June 2008). "Citation Statistics" (PDF). International Mathematical Union.

- "Not-so-deep impact". Nature. 435 (7045): 1003–1004. 23 June 2005. doi:10.1038/4351003b. PMID 15973362.

- Lozano, George A.; Larivière, Vincent; Gingras, Yves (2012). "The weakening relationship between the impact factor and papers' citations in the digital age". Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 63 (11): 2140–2145. arXiv:1205.4328. Bibcode:2012arXiv1205.4328L. doi:10.1002/asi.22731.

- Larivière, Vincent; Kiermer, Véronique; MacCallum, Catriona J.; McNutt, Marcia; Patterson, Mark; Pulverer, Bernd; Swaminathan, Sowmya; Taylor, Stuart; Curry, Stephen (2016). "A Simple Proposal for the Publication of Journal Citation Distributions". doi:10.1101/062109. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Altmetrics: A Manifesto".

- Kiermer, Veronique (2016). "Measuring Up: Impact Factors Do Not Reflect Article Citation Rates". PLOS.

- "Ditching Impact Factors for Deeper Data". The Scientist. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Corneliussen, Steven T. (2016). "Bad summer for the journal impact factor". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.5.8183.

- "International Council for Science statement". Icsu.org. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Quality not Quantity: DFG Adopts Rules to Counter the Flood of Publications in Research". Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. 23 February 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Not everything that can be counted counts …". League of European Research Universities. 16 March 2015. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- "Impact Factor, Immediacy Index, Cited Half-life". Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

-

"Bibliometrics (journal measures)". Elsevier. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

a measure of the speed at which content in a particular journal is picked up and referred to

- "Glossary of Thomson Scientific Terminology". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

-

"Journal Citation Reports Contents – Immediacy Index" ((online)). Clarivate Analytics. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

The Immediacy Index is the average number of times an article is cited in the year it is published. The journal Immediacy Index indicates how quickly articles in a journal are cited. The aggregate Immediacy Index indicates how quickly articles in a subject category are cited.

- McVeigh, Marie E.; Mann, Stephen J. (2009). "The Journal Impact Factor Denominator". JAMA. 302 (10): 1107. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1301. ISSN 0098-7484.

- Elsevier. "Metrics – Features – Scopus – Solutions | Elsevier". www.elsevier.com. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Van Noorden, Richard (2016). "Controversial impact factor gets a heavyweight rival". Nature. 540 (7633): 325–326. Bibcode:2016Natur.540..325V. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.21131. PMID 27974784.

- Jalalian M (2015). "The story of fake impact factor companies and how we detected them". Electronic Physician. 7 (2): 1069–72. doi:10.14661/2015.1069-1072. PMC 4477767. PMID 26120416.

- Jalalian, M (2015). "The story of fake impact factor companies and how we detected them". Electronic Physician. 7 (2): 1069–72. doi:10.14661/2015.1069-1072. PMC 4477767. PMID 26120416.

- Misleading Metrics Archived 2017-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Misleading Metrics – Beall's List".

- Xia, Jingfeng; Smith, Megan P. (2018). "Alternative journal impact factors in open access publishing". Learned Publishing. 31 (4): 403–411. doi:10.1002/leap.1200. ISSN 0953-1513.

- Beall, Jeffrey. "Scholarly Open-Access – Fake impact factors". Archived from the original on 21 March 2016.

- "Thomson Reuters Intellectual Property & Science Master Journal List".

- Ebrahimzadeh, Mohammad H. (April 2016). "Validated Measures of Publication Quality: Guide for Novice Researchers to Choose an Appropriate Journal for Paper Submission". Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery. 4 (2): 94–96. PMC 4852052. PMID 27200383.

Further reading

- Garfield, E (1999). "Journal impact factor: a brief review". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 161 (8): 979–980. PMC 1230709. PMID 10551195.

- Gilbert, Natasha (2010). "UK science will be judged on impact". Nature. 468 (7322): 357. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..357G. doi:10.1038/468357a. PMID 21085146.

- Groesser, Stefan N. (2012). "Dynamics of Journal Impact Factors". Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 29 (6): 624–644. doi:10.1002/sres.2142.

- Marcus, Adam; Oransky, Ivan (22 May 2015). "What's Behind Big Science Frauds?". Opinion. The New York Times.

- Lariviere, Vincent; Sugimoto, Cassidy R (2018). "The Journal Impact Factor: A brief history, critique, and discussion of adverse effects". arXiv:1801.08992 [cs.DL].

External links

- Does the 'Impact Factor' Impact Decisions on Where to Publish?, American Physical Society. Accessed: 2010-07-10.

- Scimago Journal & Country Rank: Rankings by Scopus and Scimago Lab, Scopus and Scimago Lab. Accessed: 2018-10-23.