Peripheral myelin protein 22

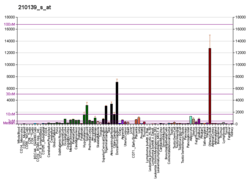

Growth arrest-specific protein 3 (GAS-3), also called peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22), is a protein which in humans is encoded by the PMP22 gene.

PMP22 is a 22 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein made up of 160 amino acids, and is mainly expressed in the Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system. Schwann cells show high expression of PMP22, where it can constitute 2-5% of total protein content in compact myelin. Compact myelin is the bulk of the peripheral neuron's myelin sheath, a protective fatty layer that provides electrical insulation for the neuronal axon.[5] The level of PMP22 expression is relatively low in the central nervous system of adults.[6]

Like other membrane proteins, newly translated PMP22 protein is temporarily sequestered to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus for post-translational modifications. PMP22 protein is glycosylated with an N terminus-linked sugar and co-localized with the chaperone protein calnexin in the ER.[7] . After the protein is transported to the Golgi apparatus it can then become incorporated in the plasma membrane of the cell.[5]

Structure and function

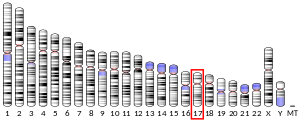

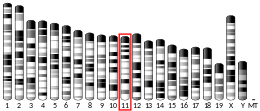

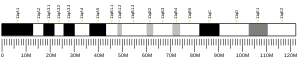

In humans, the PMP22 gene is located on chromosome 17p11.2 and spans approximately 40kb. The gene contains six exons conserved in both humans and rodents, two of which are 5’ untranslated exons (1a and 1b) and result in two different RNA transcripts with identical coding sequences. The two transcripts differ in their 5' untranslated regions and have their own promoter regulating expression. The remaining exons (2 to 5) include the coding region of the PMP22 gene, and are joined together after post-transcriptional modification (i.e. alternative splicing).[6] The PMP22 protein is characterized by four transmembrane domains, two extracellular loops (ECL1 and ECL2), and one intracellular loop.[8] ECL1 has been suggested to mediate a homophilic interaction between two PMP22 proteins, whereas ECL2 has been shown to mediate a heterophilic interaction between PMP22 protein and Myelin protein zero (MPZ).[6]

Although the PMP22 mechanism of action in myelinating Schwann cells is not fully known, it plays an essential role in the formation and maintenance of compact myelin.[5] When Schwann cells come into contact with a neuronal axon, expression of PMP22 is significantly up-regulated,[6] whereas PMP22 is down-regulated during axonal degeneration or transection.[5] PMP22 has shown association with zonula-occludens 1 and occludin, proteins that are involved in adhesion with other cells and the extracellular matrix, and also support functioning of myelin.[5] Along with cell adhesion function, PMP22 is also up-regulated during Schwann cell proliferation, suggesting a role in cell-cycle regulation. PMP22 is detectable in non-neural tissues, where its expression has been shown to serve as growth-arrest-specific (gas-3) function.[5]

Gene-dosage

Improper gene dosage of the PMP22 gene can cause aberrant protein synthesis and function of myelin sheath. Since the components of myelin are stoichiometrically set, any irregular expression of a component can cause destabilization of myelin and neuropathic disorders.[5] Alterations of PMP22 gene expression are associated with a variety of neuropathies, such as Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 1A (CMT1A), Dejerine–Sottas disease, and Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsy (HNPP). Too much PMP22 (e.g. caused by gene duplication) results in CMT1A, and too little PMP22 (e.g. caused by gene deletion) results in HNPP.[9] Gene duplication of PMP22 is the most common genetic cause of CMT[10][11] where the overproduction of PMP22 results in defects in multiple signalling pathways and dysfunction of transcriptional factors like KNOX20, SOX10 and EGR2.[5]

Interactions

Peripheral myelin protein 22 has been shown to interact with myelin protein zero.[12]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000109099 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000018217 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Watila MM, Balarabe SA (2015). "Molecular and clinical features of inherited neuropathies due to PMP22 duplication". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 355 (1–2): 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.037. PMID 26076881.

- Li J, Parker B, Martyn C, Natarajan C, Guo J (2013). "The PMP22 gene and its related diseases". Molecular Neurobiology. 47 (2): 673–98. doi:10.1007/s12035-012-8370-x. PMC 3594637. PMID 23224996.

- Dickson KM, Bergeron JJ, Shames I, Colby J, Nguyen DT, Chevet E, Thomas DY, Snipes GJ (July 2002). "Association of calnexin with mutant peripheral myelin protein-22 ex vivo: a basis for "gain-of-function" ER diseases". PNAS USA. 99 (15): 9852–857. doi:10.1073/pnas.152621799. PMC 125041. PMID 12119418.

- Nelis E, Haites N, Van Broeckhoven C (1999). "Mutations in the peripheral myelin genes and associated genes in inherited peripheral neuropathies". Human Mutation. 13 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:1<11::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 9888385.

- Brennan KM, Bai Y, Shy ME (2015). "Demyelinating CMT--what's known, what's new and what's in store?". Neuroscience Letters. 596: 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.059. PMID 25625223.

- Al-Thihli K, Rudkin T, Carson N, Poulin C, Melançon S, Der Kaloustian VM (2008). "Compound heterozygous deletions of PMP22 causing severe Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease of the Dejerine-Sottas disease phenotype". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 146A (18): 2412–6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32456. PMID 18698610.

- Berger P, Young P, Suter U (2002). "Molecular cell biology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease". Neurogenetics. 4 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10048-002-0130-z. PMID 12030326.

- D'Urso D, Ehrhardt P, Müller HW (May 1999). "Peripheral myelin protein 22 and protein zero: a novel association in peripheral nervous system myelin". The Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience. 19 (9): 3396–403. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03396.1999. PMID 10212299.

Further reading

- Patel PI, Lupski JR (Apr 1994). "Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: a new paradigm for the mechanism of inherited disease". Trends in Genetics. 10 (4): 128–33. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(94)90214-3. PMID 7518101.

- Roa BB, Lupski JR (1995). "Molecular genetics of Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy". Advances in Human Genetics. 22: 117–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-9062-7_3. ISBN 978-1-4757-9064-1. PMID 7762451.

- Nelis E, Haites N, Van Broeckhoven C (1999). "Mutations in the peripheral myelin genes and associated genes in inherited peripheral neuropathies". Human Mutation. 13 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:1<11::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 9888385.

- Jetten AM, Suter U (2000). "The peripheral myelin protein 22 and epithelial membrane protein family". Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. 64: 97–129. doi:10.1016/S0079-6603(00)64003-5. ISBN 9780125400640. PMID 10697408.