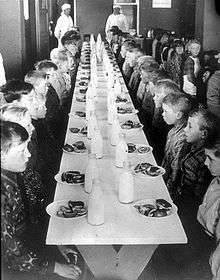

Oslo breakfast

The Oslo breakfast was a type of uncooked school meal developed in the 1920s and rolled out as a free universal provision for Oslo school children in 1932. It typically consisted of bread, cheese, milk, half an apple and half an orange.

The original Norwegian name for the meal was Oslofrokosten ("the Oslo breakfast"). The Oslo Breakfast had been designed by professor Carl Schiøtz to be as healthy as possible, with widely reported studies suggesting it delivered excellent results for the children's long-term health. During the 1930s the Oslo breakfast became famous and was copied by programs in Scandinavia, Europe, and the wider world. Many of these initiatives were small scale however, sometimes restricted to just a single school. By the late 1950s the provision of Oslo breakfasts by schools had largely ceased; sometimes they were replaced by more popular hot meal provision, or sometimes just dropped altogether as rising prosperity meant the provision of free school meals was seen as less necessary.

Ingredients

While there was some variation in the meal, its typical ingredients included:

- Two slices of wholemeal bread (Kneippbrød) spread with margarine

- A slice of cheese

- Half a pint of milk

- Half an apple and half an orange

Extra ingredients might include slices of raw uncooked vegetable, such as carrots or swedes. Between autumn and spring, a dose of cod liver oil could be included.[1][2][3][4]

History

The earliest known modern advocate for school dinners was Count Rumford, who oversaw a program to feed and educate children in late 18th-century Germany.

Oslo, or Christiana as it was then known, began to provide midday hot school meals in 1897. These meals were criticized by food scientists such as Axel Holst from as early as 1909 for not being nutritious. In the 1920s, there was still considerable poverty in Norway, including in Oslo, leading to poor nutrition. Carl Schiøtz designed the Oslo breakfast using the best scientific knowledge available at the time to make it nutritious, and began advocating for it to replace the traditional hot meal from about 1927. He later published results of experiments which found that when fed on the breakfast instead of the hot meal, the often-undernourished Oslo school children would gain more weight. As well as being a professor, Schiøtz was also a senior official in the Oslo municipal authorities, which helped him achieve the practical implementation of his ideas.[2][3][4] By 1932, the city was providing the Oslo breakfast to all primary school children.[5] Later older children were also given the meal. It was provided free of charge to all, to prevent poor children from being stigmatized if they had to apply to get it at no cost.[2][3][4]

The Oslo breakfast was the most famous of a number of similar worldwide developments in the 1920s and 1930s, for governmental and educational authorities to provide school children with more nutritious food. Perhaps the second most famous example was Lord Boyd-Orr's work in Scotland, which showed the benefits of giving school children free milk – this led to universal school milk provision across Scotland and later the whole of Great Britain.

From the 1930s to 1950s, programs based on the Oslo breakfast soon spread to other Norwegian cities, across Scandinavia, the rest of Europe, and to the wider world, including countries like Australia and Canada. As an example of the positive reports from trials of the breakfast, Jack Drummond of London University said that after 130 poor children had been fed on the breakfast, effects had been "remarkable".[4] The children had lost the poor skin conditions common at the time, and had enjoyed a 25% gain in height over those not having the breakfast.[2][3][4][6]

The worldwide popularity of the Oslo breakfast reached its peak around the mid-1950s, and then began to decline. In some areas it had been introduced as a supplementary meal to school lunch, not as a replacement as had originally been the case in Oslo. Schools found that running two meal programs reduced their teaching time, and chose to eliminate the breakfast rather than the more popular lunch. In the late 1950s the Oslo breakfast ceased to be provided in its home country: With Norway now much more prosperous, authorities saw no need to continue to provide any form of free school meal. Norwegian parents took over, providing a packed lunch with similar ingredients to the original breakfast.[2][3]

Other uses

British food writer Marguerite Patten refers to the Oslo breakfast as a light alternative to the traditional cooked breakfast, in a 1955 book aimed at "brides and beginners". In this context it is a meal at home, resembling a savoury Continental breakfast.[7]

See also

- List of breakfast topics

- School breakfast club

- School meals initiative for healthy children

Notes and references

- O B Grimley (1939). The New Norway: A People with the Spirit of Cooperation. John Grundt Tanum. pp. 112–136. ASIN B000KUAQ4A.

- Inger Johanne Lyngø (1998). "The Oslo breakfast : an optimal diet in one meal : on the scientification of everyday life as exemplified by food". Ethnologia scandinavica. 28.

- Astri Andresen and Kari Tove Elvbakken (2007). "From poor law society to the welfare state: school meals in Norway 1890s–1950s". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 61. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.048132. PMC 2465698. PMID 17435200.

- Gordon W. Gunderson (29 January 2013). "History of School dinners". Food and Nutrition Service. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "Skolemåltidets historie" (in Norwegian). Opplysningskontoret for frukt og grønt. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Amy Staples (2006). The Birth of Development: How the World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization, and World Health Organization Changed the World, 1945–1965. Kent State University Press. pp. 64–69. ISBN 0873388496.

- Learning to cook with Marguerite Patten. Phoenix House: London. 1955