Ornithopter

An ornithopter (from Greek ornithos "bird" and pteron "wing") is an aircraft that flies by flapping its wings. Designers seek to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Though machines may differ in form, they are usually built on the same scale as these flying creatures. Manned ornithopters have also been built, and some have been successful. The machines are of two general types: those with engines, and those powered by the muscles of the pilot.

Early history

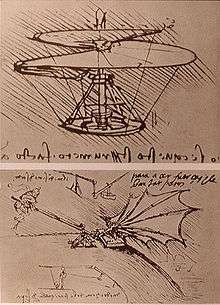

Some early manned flight attempts may have been intended to achieve flapping-wing flight, but probably only a glide was actually achieved. They include the purported flights of the 11th-century monk Eilmer of Malmesbury (recorded in the 12th century) and the 9th-century poet Abbas Ibn Firnas (recorded in the 17th century).[1] Roger Bacon, writing in 1260, was also among the first to consider a technological means of flight. In 1485, Leonardo da Vinci began to study the flight of birds. He grasped that humans are too heavy, and not strong enough, to fly using wings simply attached to the arms. He, therefore, sketched a device in which the aviator lies down on a plank and works two large, membranous wings using hand levers, foot pedals, and a system of pulleys.

In 1841, an ironsmith kalfa (journeyman), Manojlo, who "came to Belgrade from Vojvodina",[2] attempted flying with a device described as an ornithopter ("flapping wings like those of a bird"). Refused by the authorities a permit to take off from the belfry of Saint Michael's Cathedral, he clandestinely climbed to the rooftop of the Dumrukhana (import tax head office) and took off, landing in a heap of snow, and surviving.[3]

The first ornithopters capable of flight were constructed in France. Jobert in 1871 used a rubber band to power a small model bird. Alphonse Pénaud, Abel Hureau de Villeneuve, and Victor Tatin, also made rubber-powered ornithopters during the 1870s.[4] Tatin's ornithopter was perhaps the first to use active torsion of the wings, and apparently it served as the basis for a commercial toy offered by Pichancourt c. 1889. Gustave Trouvé was the first to use internal combustion, and his 1890 model flew a distance of 80 meters in a demonstration for the French Academy of Sciences. The wings were flapped by gunpowder charges activating a Bourdon tube.

From 1884 on, Lawrence Hargrave built scores of ornithopters powered by rubber bands, springs, steam, or compressed air.[5] He introduced the use of small flapping wings providing the thrust for a larger fixed wing; this innovation eliminated the need for gear reduction, thereby simplifying the construction.

E.P. Frost made ornithopters starting in the 1870s; first models were powered by steam engines, then in the 1900s, an internal-combustion craft large enough for a person was built, though it did not fly.[6]

In the 1930s, Alexander Lippisch and the National Socialist Flyers Corps of Nazi Germany constructed and successfully flew a series of internal combustion-powered ornithopters, using Hargrave's concept of small flapping wings, but with aerodynamic improvements resulting from the methodical study.

Erich von Holst, also working in the 1930s, achieved great efficiency and realism in his work with ornithopters powered by rubber bands. He achieved perhaps the first success of an ornithopter with a bending wing, intended to imitate more closely the folding wing action of birds, although it was not a true variable-span wing-like those of birds.[7]

Around 1960, Percival Spencer successfully flew a series of unmanned ornithopters using internal combustion engines ranging from 0.020-to-0.80-cubic-inch (0.33 to 13.11 cm3) displacement, and having wingspans up to 8 feet (2.4 m).[8] In 1961, Percival Spencer and Jack Stephenson flew the first successful engine-powered, remotely piloted ornithopter, known as the Spencer Orniplane.[9] The Orniplane had a 90.7-inch (2,300 mm) wingspan, weighed 7.5 pounds (3.4 kg), and was powered by a 0.35-cubic-inch (5.7 cm3)-displacement two-stroke engine. It had a biplane configuration, to reduce oscillation of the fuselage.[10]

Manned flight

Manned ornithopters fall into two general categories: Those powered by the muscular effort of the pilot (human-powered ornithopters), and those powered by an engine.

Around 1894, Otto Lilienthal, an aviation pioneer, became famous in Germany for his widely publicized and successful glider flights. Lilienthal also studied bird flight and conducted some related experiments. He constructed an ornithopter, although its complete development was prevented by his untimely death on 9 August 1896 in a glider accident.

In 1929, a man-powered ornithopter designed by Alexander Lippisch (designer of the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet) flew a distance of 250 to 300 metres (800–1,000 ft) after tow launch. Since a tow launch was used, some have questioned whether the aircraft was capable of flying on its own. Lippisch asserted that the aircraft was actually flying, not making an extended glide. (Precise measurement of altitude and velocity over time would be necessary to resolve this question.) Most of the subsequent human-powered ornithopters likewise used a tow launch, and flights were brief simply because human muscle power diminishes rapidly over time.

In 1942, Adalbert Schmid made a much longer flight of a human-powered ornithopter at Munich-Laim. It travelled a distance of 900 metres (3,000 ft), maintaining a height of 20 metres (65 ft) throughout most of the flight. Later this same aircraft was fitted with a three-horsepower (2.2 kW) Sachs motorcycle engine. With the engine, it made flights up to 15 minutes in duration. Schmid later constructed a 10-horsepower (7.5 kW) ornithopter, based on the Grunau-Baby IIa sailplane, which was flown in 1947. The second aircraft had flapping outer wing panels.[11]

In 2005, Yves Rousseau was given the Paul Tissandier Diploma, awarded by the FAI for contributions to the field of aviation. Rousseau attempted his first human-muscle-powered flight with flapping wings in 1995. On 20 April 2006, at his 212th attempt, he succeeded in flying a distance of 64 metres (210 ft), observed by officials of the Aero Club de France. On his 213th flight attempt, a gust of wind led to a wing breaking up, causing the pilot to be gravely injured and rendered paraplegic.[12]

A team at the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies, headed by Professor James DeLaurier, worked for several years on an engine-powered, piloted ornithopter. In July 2006, at the Bombardier Airfield at Downsview Park in Toronto, Professor DeLaurier's machine, the UTIAS Ornithopter No.1 made a jet-assisted takeoff and 14-second flight. According to DeLaurier,[13] the jet was necessary for sustained flight, but the flapping wings did most of the work.[14]

On August 2, 2010, Todd Reichert of the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies piloted a human-powered ornithopter named Snowbird. The 32-metre (105 ft) wingspan, 42-kilogram (93 lb) aircraft was constructed from carbon fibre, balsa, and foam. The pilot sat in a small cockpit suspended below the wings and pumped a bar with his feet to operate a system of wires that flapped the wings up and down. Towed by a car until airborne, it then sustained flight for almost 20 seconds. It flew 145 metres (476 ft) with an average speed of 25.6 km/h (15.9 mph).[15] Similar tow-launched flights were made in the past, but improved data collection verified that the ornithopter was capable of self-powered flight once aloft.[16]

Applications for unmanned ornithopters

Practical applications capitalize on the resemblance to birds or insects. Colorado Parks and Wildlife has used these machines to help save the endangered Gunnison sage grouse. An artificial hawk under the control of an operator causes the grouse to remain on the ground so they can be captured for study.

Because ornithopters can be made to resemble birds or insects, they could be used for military applications such as aerial reconnaissance without alerting the enemies that they are under surveillance. Several ornithopters have been flown with video cameras on board, some of which can hover and maneuver in small spaces. In 2011, AeroVironment, Inc. demonstrated a remotely piloted ornithopter resembling a large hummingbird for possible spy missions.

Led by Paul B. MacCready (of Gossamer Albatross), AeroVironment, Inc. developed a half-scale radio-controlled model of the giant pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, for the Smithsonian Institution in the mid-1980s. It was built to star in the IMAX movie On the Wing. The model had a 5.5-metre (18 ft) wingspan and featured a complex computerized autopilot control system, just as the full-sized pterosaur relied on its neuromuscular system to make constant adjustments in flight.[17][18][19]

Researchers hope to eliminate the motors and gears of current designs by more closely imitating animal flight muscles. Georgia Tech Research Institute's Robert C. Michelson is developing a reciprocating chemical muscle for use in microscale flapping-wing aircraft. Michelson uses the term "entomopter" for this type of ornithopter.[20] SRI International is developing polymer artificial muscles that may also be used for flapping-wing flight.

In 2002, Krister Wolff and Peter Nordin of Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, built a flapping-wing robot that learned flight techniques.[21] The balsa-wood design was driven by machine learning software technology known as a steady-state linear evolutionary algorithm. Inspired by natural evolution, the software "evolves" in response to feedback on how well it performs a given task. Although confined to a laboratory apparatus, their ornithopter evolved behavior for maximum sustained lift force and horizontal movement.[22]

Since 2002, Prof. Theo van Holten has been working on an ornithopter that is constructed like a helicopter. The device is called the "ornicopter"[23] and was made by constructing the main rotor so that it would have no reaction torque.

In 2008, Amsterdam Airport Schiphol started using a realistic-looking mechanical hawk designed by falconer Robert Musters. The radio-controlled robot bird is used to scare away birds that could damage the engines of airplanes.[24][25]

In 2012, RoBird (formerly Clear Flight Solutions), a spin-off of the University of Twente, started making artificial birds of prey (called RoBird®) for airports and agricultural and waste-management industries.[26][27]

Adrian Thomas (zoologist) and Alex Caccia founded Animal Dynamics Ltd in 2015, to develop a mechanical analogue of dragonflies to be used as a drone that will outperform quadcopters. The work is funded by the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, the research arm of the British Ministry of Defence, and the United States Air Force.[28]

In 2017, researchers of the University of Illinois made an ornithopter that flies like a bat.[29] The device, called Bat Bot (B2) is intended to be used for construction site inspection. Bat wings are fundamentally different from bird wings, and it’s not just because birds have feathers and bats don’t. Generally, when roboticists design bird-inspired or insect-inspired robots, they use rigid approximations of the wings, or perhaps a few different rigid parts flexibly interconnected. Bat wings don’t work like this at all: The underlying structure of a bat’s wing is made up of “a metamorphic musculoskeletal system that has more than 40 degrees of freedom” and includes bones that actively deform during every wing beat. The wing surface itself is an “anisotropic wing membrane skin with adjustable stiffness.” This level of complexity is what gives bats their unrivaled level of agility, according to the researchers, but it also makes bats wicked hard to turn into robots.[30] The dominant degrees of freedom (DOFs) in the bat flight mechanism are identified and incorporated in B2’s design by means of a series of mechanical constraints. These biologically meaningful DOFs include asynchronous and mediolateral movements of the armwings and dorsoventral movements of the legs. Also, the continuous surface and elastic properties of bat skin under wing morphing are realized by an ultrathin (56 micrometers) membranous skin that covers the skeleton of the morphing wings. We have successfully achieved autonomous flight of B2 using a series of virtual constraints to control the articulated, morphing wings .[31]

Hobby

Hobbyists can build and fly their own ornithopters. These range from light-weight models powered by rubber bands, to larger models with radio control.

The rubber-band-powered model can be fairly simple in design and construction. Hobbyists compete for the longest flight times with these models. An introductory model can be fairly simple in design and construction, but the advanced competition designs are extremely delicate and challenging to build. Roy White holds the United States national record for indoor rubber-powered, with his flight time of 21 minutes, 44 seconds.

Commercial free-flight rubber-band powered toy ornithopters have long been available. The first of these was sold under the name Tim Bird in Paris in 1879.[32] Later models were also sold as Tim Bird (made by G de Ruymbeke, France, since 1969).

Commercial radio-controlled designs stem from Percival Spencer's engine-powered Seagulls, developed circa 1958, and Sean Kinkade's work in the late 1990s to present day. The wings are usually driven by an electric motor. Many hobbyists enjoy experimenting with their own new wing designs and mechanisms. The opportunity to interact with real birds in their own domain also adds great enjoyment to this hobby. Birds are often curious and will follow or investigate the model while it is flying. In a few cases, RC birds have been attacked by birds of prey, crows, and even cats. More recent cheaper models such as the Dragonfly from WowWee have extended the market from dedicated hobbyists to the general toy market.

Some helpful resources for hobbyists include The Ornithopter Design Manual, book written by Nathan Chronister, and The Ornithopter Zone web site, which includes a large amount of information about building and flying these models.

Ornithopters are also of interest as the subject of one of the events in the nationwide Science Olympiad event list. The event ("Flying Bird") entails building a self-propelled ornithopter to exacting specifications, with points awarded for high flight time and low weight. Bonus points are also awarded if the ornithopter happens to look like a real bird.

Aerodynamics

As demonstrated by birds, flapping wings offer potential advantages in maneuverability and energy savings compared with fixed-wing aircraft, as well as potentially vertical take-off and landing. It has been suggested that these advantages are greatest at small sizes and low flying speeds,[33] but the development of comprehensive aerodynamic theory for flapping remains an outstanding problem due to the complex non-linear nature of such unsteady separating flows.[34]

Unlike airplanes and helicopters, the driving airfoils of the ornithopter have a flapping or oscillating motion, instead of rotary. As with helicopters, the wings usually have a combined function of providing both lift and thrust. Theoretically, the flapping wing can be set to zero angle of attack on the upstroke, so it passes easily through the air. Since typically the flapping airfoils produce both lift and thrust, drag-inducing structures are minimized. These two advantages potentially allow a high degree of efficiency.

Wing design

If future manned motorized ornithopters cease to be "exotic", imaginary, unreal aircraft and start to serve humans as junior members of the aircraft family, designers and engineers will need to solve not only wing design problems but many other problems involved in making them safe and reliable aircraft. Some of these problems, such as stability, controllability, and durability, are inherent to all aircraft. Other problems specific to ornithopters will appear; optimizing flapping-wing design is only one of them.

An effective ornithopter must have wings capable of generating both thrust, the force that propels the craft forward, and lift, the force (perpendicular to the direction of flight) that keeps the craft airborne. These forces must be strong enough to counter the effects of drag and the weight of the craft.

Leonardo's ornithopter designs were inspired by his study of birds, and conceived the use of flapping motion to generate thrust and provide the forward motion necessary for aerodynamic lift. However, using materials available at that time the craft would be too heavy and require too much energy to produce sufficient lift or thrust for flight. Alphonse Pénaud introduced the idea of a powered ornithopter in 1874. His design had limited power and was uncontrollable, causing it to be transformed into a toy for children.[35] More recent vehicles, such as the human-powered ornithopters of Lippisch (1929) and Emil Hartman (1959), were capable powered gliders but required a towing vehicle in order to take off and may not have been capable of generating sufficient lift for sustained flight. Hartman's ornithopter lacked the theoretical background of others based on the study of winged flight, but exemplified the idea of an ornithopter as a birdlike machine rather than a machine that directly copies birds' method of flight.[36][37] The 1960s saw powered unmanned ornithopters of various sizes capable of achieving and sustaining flight, providing valuable real-world examples of mechanical winged flight. In 1991, Harris and DeLaurier flew the first successful engine-powered remotely piloted ornithopter in Toronto, Canada. In 1999, a piloted ornithopter based on this design flew, capable of taking off from level pavement and executing sustained flight.[36]

An ornithopter's flapping wings and their motion through the air are designed to maximize the amount of lift generated within limits of weight, material strength and mechanical complexity. A flexible wing material can increase efficiency while keeping the driving mechanism simple. In wing designs with the spar sufficiently forward of the airfoil that the aerodynamic center is aft of the elastic axis of the wing, aeroelastic deformation causes the wing to move in a manner close to its ideal efficiency (in which pitching angles lag plunging displacements by approximately 90 degrees.)[38] Flapping wings increase drag and are not as efficient as propeller-powered aircraft. Some designs achieve increased efficiency by applying more power on the down stroke than on the upstroke, as do most birds.[35]

In order to achieve the desired flexibility and minimum weight, engineers and researchers have experimented with wings that require carbon fiber, plywood, fabric, and ribs, with a stiff, strong trailing edge.[39] Any mass located aft of the empennage reduces the wing's performance, so lightweight materials and empty space are used where possible. To minimize drag and maintain the desired shape, choice of a material for the wing surface is also important. In DeLaurier's experiments, a smooth aerodynamic surface with a double-surface airfoil is more efficient at producing lift than a single-surface airfoil.

Other ornithopters do not necessarily act like birds or bats in flight. Typically birds and bats have thin and cambered wings to produce lift and thrust. Ornithopters with thinner wings have a limited angle of attack but provide optimum minimum-drag performance for a single lift coefficient.[40]

Although hummingbirds fly with fully extended wings, such flight is not feasible for an ornithopter. If an ornithopter wing were to fully extend and twist and flap in small movements it would cause a stall, and if it were to twist and flap in very large motions, it would act like a windmill causing an inefficient flying situation.[41]

A team of engineers and researchers called "Fullwing" has created an ornithopter that has an average lift of over 8 pounds, an average thrust of 0.88 pounds, and a propulsive efficiency of 54%.[42] The wings were tested in a low-speed wind tunnel measuring the aerodynamic performance, showing that the higher the frequency of the wing beat, the higher the average thrust of the ornithopter.

Appearance in fiction

- Dune

- Chicken Run

- The Half-Made World

- The Airborn Trilogy

- Freak The Mighty

- Birdy

- Magic: The Gathering

- The Number Of The Beast

See also

- Gyroplane

- Helicopter

- Human-powered aircraft

- Insectothopter

- Micro air vehicle

- Micromechanical Flying Insect

- Nano Hummingbird

- Rotary-wing aircraft

- STOL/VTOL/STOVL/VSTOL

References

- White, Lynn. "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition." Technology and Culture, Volume 2, Issue 2, 1961, pp. 97–111 (97–99 resp. 100–101).

- инфо, СРБИН (17 November 2014). "ЈЕДАН СРБИН ЈЕ ПОКУШАО ДА ЛЕТИ: Ово је прича о српском Икару, калфи Манојлу". СРБИН.ИНФО.

- "Vremeplov: 100 godina avijacije u Srbiji". Vesti online.

- Chanute, Octave. 1894, reprinted 1998. Progress in Flying Machines. Dover ISBN 0-486-29981-3

- W. Hudson Shaw and Olaf Ruhen. 1977. Lawrence Hargrave: Explorer, Inventor & Aviation Experimenter. Cassell Australia Ltd. pp. 53–160.

- Kelly, Maurice. 2006. Steam in the Air. Ben & Sword Books. Pages 49–55 are about Frost.

- Rubber Band Powered Ornithopters at Ornithopter Zone web site

- The complete book of model aircraft, spacecraft, and rockets − by Louis H. Hertz, Bonanza Books, 1968.

- Video provided by Jack Stephenson: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vS4Yz-VcNes

- RC History Brought Back to Life: Spencer's Ornithopter, by Faye Stilley, Feb 1999 Model Airplane News

- Bruno Lange, Typenhandbuch der deutschen Luftfahrttechnik, Koblenz, 1986. Archived 2007-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- FAI web site. Archived July 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Dr. James DeLaurier's report on the Flapper's Flight July 8, 2006

- University of Toronto ornithopter takes off July 31, 2006

- Human-Powered Ornithoper Flight in Flapping Wings: The Ornithopter Zone Newsletter, Fall 2010.

- "HPO Team News - Human Powered Ornithopter Project -". hpo.ornithopter.net.

- Anderson, Ian (10 October 1985), "Winged lizard takes to the air of California", New Scientist (1477): 31, retrieved 20 October 2010

- MacCready, Paul (November 1985), "The Great Pterodactyl Project" (PDF), Engineering & Science: 18–24, retrieved 20 October 2010

- Schefter, Jim (March 1986), "Look! Up in the sky! It's a bird, it's a plane it's a pterodactyl", Popular Science: 78–79, 124, retrieved 20 October 2010

- "About Robert C. Michelson's Micro Air Vehicle "Entomopter" Project". angel-strike.com.

- Winged robot learns to fly New Scientist, August 2002

- Creation of a learning, flying robot by means of Evolution In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, GECCO 2002 (pp. 1279–1285). New York, 9–13 July 2002. Morgan Kaufmann. Awarded "Best Paper in Evolutionary Robotics" at GECCO 2002.

- Ornicopter project Archived 2006-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Article in Dutch newspaper Trouw, partial translation:..."The so-called 'Horck', an electrical controllable bird is the newest means to scare birds. Because they can cause much damage to airplanes. (...) ...it is a design by Robert Musters, a falconer from Enschede"

- A picture Archived 2009-06-14 at the Wayback Machine of the bird with English description

- "Effective Bird Control — Clear Flight Solutions". clearflightsolutions.com.

- "Hannover Messe Challenge". Universiteit Twente.

- "Animal Dynamics web-site". Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Ramezani, Alireza; Chung, Soon-Jo; Hutchinson, Seth (1 February 2017). "A biomimetic robotic platform to study flight specializations of bats" (PDF). Science Robotics. 2 (3): eaal2505. doi:10.1126/scirobotics.aal2505.

- Ackerman, Evan (1 February 2017). "Bat Robot Offers Safety and Maneuverability in Bioinspired Design". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News.

- Ramezani, Alireza; Chung, Soon-Jo; Hutchinson, Seth (1 February 2017). "A biomimetic robotic platform to study flight specializations of bats" (PDF). Science Robotics. 2 (3): eaal2505. doi:10.1126/scirobotics.aal2505.

- "FLYING HIGH: Bird Man". Scientific American Frontiers Archive. Archived from the original on 2007-02-10. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- T.J. Mueller and J.D. DeLaurier, "An Overview of Micro Air Vehicle Aerodynamics", Fixed and Flapping Wing Aerodynamics for Micro Air Vehicle Applications, Paul Zarchan, Editor-in-Chief, Volume 195, AIAA, 2001

- Buchner, A. J.; Honnery, D.; Soria, J. (2017). "Stability and three-dimensional evolution of a transitional dynamic stall vortex". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 823: 166–197. Bibcode:2017JFM...823..166B. doi:10.1017/jfm.2017.305.

- "An Ornithopter Wing Design" DeLaurier, James D. (1994), 10–18 (accessed November 30, 2010)

- "Aeroelastic Design and Manufacture of an Efficient Ornithopter Wing Archived 2011-03-04 at the Wayback Machine" Benedict, Moble. 3–4.

- "Project Ornithopter - History". www.ornithopter.net.

- "The development of an efficient ornithopter wing" DeLaurier, J.D. (1993), 152–162 (accessed May 27, 2014)

- "The development of an efficient ornithopter wing" DeLaurier, J.D. (1993), 152–162, (accessed May 27, 2014)

- Warrick, Douglas, Bret Tobalske, Donald Powers, and Michael Dickinson. "The Aerodynamics of Hummingbird Flight Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1–5. Web. 30 Nov 2010.

- Liger, Matthieu, Nick Pornsin-Sirirak, Yu-Chong Tai, Steve Ho, and Chih-Ming Ho. "Large-Area Electrostatic-Valved Skins for Adaptive Flow Control on Ornithopter Wings" (2002): 247–250. 30 Nov 2010.

- DeLaurier, James D. "An Ornithopter Wing Design" 40. 1 (1994), 10–18, (accessed November 30, 2010)

Further reading

- Chronister, Nathan. (1999). The Ornithnopter Design Manual. Published by The Ornithopter Zone.

- Mueller, Thomas J. (2001). "Fixed and flapping wing aerodynamics for micro air vehicle applications". Virginia: American Inst. of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1-56347-517-0

- Azuma, Akira (2006). "The Biokinetics of Flying and Swimming". Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2nd Edition. ISBN 1-56347-781-5.

- DeLaurier, James D. "The Development and Testing of a Full-Scale Piloted Ornithopter." Canadian Aeronautics and Space Journal. 45. 2 (1999), 72–82. (accessed November 30, 2010).

- Warrick, Douglas, Bret Tobalske, Donald Powers, and Michael Dickinson. "The Aerodynamics of Hummingbird Flight." American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1–5. Web. 30 Nov 2010.

- Crouch, Tom D. Aircraft of the National Air and Space Museum. Fourth ed. Lilienthal Standard Glider. Smithsonian Institution, 1991.

- Bilstein, Roger E. Flight in America 1900–1983. First ed. Gliders and Airplanes. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984. (pages 8–9)

- Crouch, Tom D. Wings. A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age. First ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2003. (pages 44–53)

- Anderson, John D. A history of aerodynamics and its impact on flying machines. Cambridge: United Kingdom, 1997.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ornithopters. |