Asimina

Asimina is a genus of small trees or shrubs described as a genus in 1763.[2][3]

| Pawpaw | |

|---|---|

| |

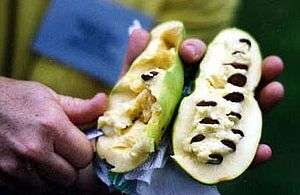

| Asimina triloba (common pawpaw) in fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Annonaceae |

| Genus: | Asimina Adans. |

| Type species | |

| Asimina triloba | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Asimina has large simple leaves and large fruit. It is native to eastern North America and collectively referred to as pawpaw. The genus includes the widespread common pawpaw Asimina triloba, which bears the largest edible fruit indigenous to the continent.[4] Pawpaws are native to 26 states of the U.S. and to Ontario in Canada.[4][5] The common pawpaw is a patch-forming (clonal) understory tree found in well-drained, deep, fertile bottomland and hilly upland habitat. Pawpaws are in the same plant family (Annonaceae) as the custard-apple, cherimoya, sweetsop, soursop, and ylang-ylang;[6] the genus is the only member of that family not confined to the tropics.

Names

.png)

The genus name Asimina was first described and named by Michel Adanson, a French naturalist of Scottish descent. The name is adapted from the Native American name assimin[7] through the French colonial asiminier.[8]

The common name pawpaw, also spelled paw paw, paw-paw, and papaw, probably derives from the Spanish papaya, perhaps because of the superficial similarity of their fruits.[9]

Description

Pawpaws are shrubs or small trees to 2–12 m (6.6–39.4 ft) tall. The northern, cold-tolerant common pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is deciduous, while the southern species are often evergreen.

The leaves are alternate, obovate, entire, 20–35 cm (7.9–13.8 in) long and 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) broad.

The flowers of pawpaws are produced singly or in clusters of up to eight together; they are large, 4–6 cm across, perfect, with six sepals and petals (three large outer petals, three smaller inner petals). The petal color varies from white to purple or red-brown.

The fruit of the common pawpaw is a large edible berry, 5–16 cm (2.0–6.3 in) long and 3–7 cm (1.2–2.8 in) broad, weighing from 20–500 g (0.71–17.64 oz), with numerous seeds; it is green when unripe, maturing to yellow or brown. It has a flavor somewhat similar to both banana and mango, varying significantly by cultivar, and has more protein than most fruits.[4]

Species and their distributions

- Asimina angustifolia Raf. 1840 not A. Gray 1886; Florida, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina[13] Not a valid species [14]

- Asimina incana (W. Bartram) Exell - woolly pawpaw. Florida and Georgia. (Annona incana W. Bartram[15])

- Asimina longifolia Raf. - slimleaf pawpaw. Florida, Georgia, and Alabama.

- Asimina manasota DeLaney - manasota papaw native to two counties in Florida (Manatee + Sarasota); first described in 2010[16] Not a valid species [14]

- Asimina × nashii Kral. - Florida and Georgia.

- Asimina obovata (Willd.) Nash) (Annona obovata Willd.)- flag-pawpaw or bigflower pawpaw - Florida [17][18]

- Asimina parviflora (Michx.) Dunal - smallflower pawpaw. Southern states from Texas to Virginia.

- Asimina pygmaea (W. Bartram) Dunal - dwarf pawpaw. Florida and Georgia.

- Asimina reticulata Shuttlw. ex Chapman - netted pawpaw. Florida and Georgia.

- Asimina spatulata (Kral) D.B.Ward - slim leaf pawpaw. Florida and Alabama[19] Not a valid species [14]

- Asimina tetramera Small - fourpetal pawpaw. Florida (endangered)

- Asimina triloba (L.) Dunal - common pawpaw. Extreme southern Ontario, Canada, and the eastern United States from New York west to southeast Nebraska, and south to northern Florida and eastern Texas. (Annona triloba L.[20])

Ecology

The common pawpaw is native to shady, rich bottom lands, where it often forms a dense undergrowth in the forest, often appearing as a patch or thicket of individual small slender trees.

Pawpaw flowers are insect-pollinated, but fruit production is limited since few if any pollinators are attracted to the flower's faint, or sometimes non-existent scent. The flowers produce an odor similar to that of rotting meat to attract blowflies or carrion beetles for cross pollination.[21] Other insects that are attracted to pawpaw plants include scavenging fruit flies, carrion flies and beetles. Because of difficult pollination, some believe the flowers are self-incompatible.

Pawpaw fruit may be eaten by foxes, opossums, squirrels and raccoons. However, pawpaw leaves and twigs are seldom consumed by rabbits or deer.[22]

The leaves, twigs, and bark of the common pawpaw tree contain natural insecticides known as acetogenins.[23]

Larvae of the zebra swallowtail butterfly feed exclusively on young leaves of the various pawpaw species, but never occur in great numbers on the plants.[24]

The paw paw in considered an evolutionary anachronism, where a now-extinct evolutionary partner, such as a Pleistocene megafauna species, formerly consumed the fruit and assisted in seed dispersal.[25]

Cultivation and uses

Wild-collected fruits of the common pawpaw (Asimina triloba) have long been a favorite treat throughout the tree's extensive native range in eastern North America.[4] Fresh pawpaw fruits are commonly eaten raw; however, they do not store or ship well unless frozen.[4] The fruit pulp is also often used locally in baked dessert recipes, with pawpaw often substituted in many banana-based recipes.

Pawpaws have never been cultivated for fruit on the scale of apples and peaches, but interest in pawpaw cultivation has increased in recent decades.[4] However, only frozen fruit will store or ship well. Other methods of preservation include dehydration, production of jams or jellies, and pressure canning.

The pawpaw is also gaining in popularity among backyard gardeners because of the tree's distinctive growth habit, the appeal of its fresh fruit, and its relatively low maintenance needs once established. The common pawpaw is also of interest in ecological restoration plantings since this tree grows well in wet soil and has a strong tendency to form well-rooted clonal thickets.

The several other species of Asimina have few economic uses.

History

The earliest documentation of pawpaws is in the 1541 report of the Spanish de Soto expedition, who found Native Americans cultivating it east of the Mississippi River. Chilled pawpaw fruit was a favorite dessert of George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson planted it at his home in Virginia, Monticello. The Lewis and Clark Expedition sometimes subsisted on pawpaws during their travels. Daniel Boone was also a consumer and fan of the pawpaw. The common pawpaw was designated as the Ohio state native fruit in 2009.[26][27]

References

- Flora of North America Vol. 3, Pawpaw, Asimina Adanson, Fam. Pl. 2: 365. 1763.

- Adanson, Michel. 1763. Familles des Plantes 2: 365 in French

- Tropicos, Asimina Adans.

- "Pawpaw Description and Nutritional Information". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Flora of North America: Asimina triloba. "Asimina triloba". Flora of North America. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Boning, Charles R. (2006). Florida's Best Fruiting Plants: Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. pp. 172–173. ISBN 1561643726.

- Werthner, William B. (1935). Some American Trees: An intimate study of native Ohio trees. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. xviii + 398 pp.

- Sargent, Charles Sprague (1933). Manual of the trees of North America (exclusive of Mexico). Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company: The Riverside Press Cambridge. pp. xxvi + 910.

- Hormanza, José I. (July 2014). "The Pawpaw, a Forgotten North American Fruit Tree" (PDF). semanticscholar.org.

- The Plant List, search for Asimina

- "Asimina". Flora of North America. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- Biota of North America Program 2013 county distribution maps, Asimina

- Biota of North America Program 2013 county distribution maps, Asimina angustifolia

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-03-12. Retrieved 2014-09-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Annona incana". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- "Asimina manasota - Species Page - ISB: Atlas of Florida Plants".

- US Department of Agriculture plants profile, Asimina obovata (Willd.) Nash, bigflower pawpaw

- "Asimina obovata". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- Alabama Plant Atlas, Asimina spatulata

- "Asimina triloba". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- Guy Hand (October 12, 2011). "In Awe of the Pawpaw". Boise Weekly. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "PAWPAW Fruit Facts".

- Sampson, B.J., J.L. McLaughlin, D.E. Wedge. 2003. PawPaw Extract as a Botanical Insecticide, 2002. Arthropod Management Tests, vol.28, p.L

- California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc. 1996,1999, "Pawpaw: Asimina triloba, Annonaceae"

- Madison J. Boone, Charli N. Davis, Laura Klasek, Jillian F. del Sol, Katherine Roehm, and Matthew D. Moran "A Test of Potential Pleistocene Mammal Seed Dispersal in Anachronistic Fruits using Extant Ecological and Physiological Analogs," Southeastern Naturalist 14(1), 22-32, (1 March 2015). https://doi.org/10.1656/058.014.0109

- Craig Summers Black (February 4, 2009). "America's forgotten fruit: The native pawpaw tastes like banana and grows close to home". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 2009-03-14.

- Ohio Revised Code 5.082

External links

- Flora of North America Asimina

- USDA distribution of Pawpaw

- Pawpaw Information from Kentucky State University

- Asimina Genetic Resources

- Clark's September 18, 1806 journal entry about pawpaws

- Asimina triloba - Brooklyn Botanical Garden

- Asimina Genetic Resources - Pawpaw

- Pawpaw Wines

- Pawpaw Festival, Athens, Ohio

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Asimina. |