Orange Herald

Orange Herald was a British nuclear weapon, tested on 31 May 1957. At the time it was reported as a H-bomb, although in fact it was a large boosted fission weapon.

Technical

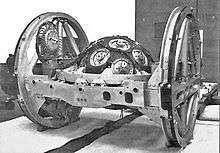

Orange Herald was a fusion boosted British fission nuclear weapon (called a core-boosted device by the British), comprising a U-235 core containing a small amount of lithium deutero tritide (LiD/LiT).[1][2] 'Herald' was suitable for mounting on a missile, utilizing 117 kg of U-235. However, Britain's annual production of U-235 was only 120 kg at this time, which would have made such weapons rare and very expensive.[3]

Two versions were designed - an "Orange Herald Large" with an overall diameter of 39 inches (1.0 m), and an "Orange Herald Small" with overall diameter of 30 inches (0.75 m).[3] The difference between the two was in the size of the high explosives; the fissile cores were similar. Orange Herald Small was intended as a warhead for a ballistic missile. Orange Herald Large was designed as device which would have the most certainty to give a yield in the megaton range. However, due to its size it was not suited as a warhead for the ballistic missile and was more of an insurance which could be used if other devices failed to achieve the desired yield.

The Orange Herald Small version was tested once, yielding 720 kt of explosive power on 31 May 1957, during the Grapple 2/Orange Herald tests on Malden Island in the Pacific.[4] Orange Herald remains the largest fission device ever tested.

It is thought that the fusion boosting failed to increase the yield. A higher compression but smaller fission pit American weapon, the Mark 18 Super Oralloy Bomb, had a yield of 500 kilotons from a pit with slightly over 60 kilograms of highly enriched uranium, around 8 kilotons per kilogram of uranium, about the practical maximum 50% fission yield efficiency for very large or very highly boosted fission weapons. Even with less compression, the larger 117 kg pit of HEU in the Orange Herald Small should have had a roughly similar efficiency, but the observed 720 kiloton yield equals only just over 6 kilotons per kilogram of uranium.

Orange Herald was the first British nuclear device to use an external neutron source.[5]

History

Britain rushed the development of these predicted-megaton class weapons because in 1955 it seemed that atmospheric testing could soon be outlawed by treaty. As a result, the UK wanted to demonstrate its ability to manufacture megaton class weapons by proof-testing them before any legal prohibitions were in place. According to an article in New Scientist, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was also hoping to convince the US to change the McMahon Act, which prohibited sharing information even with the British, by demonstrating that the UK had the technology to make a thermonuclear weapon (an H-bomb), and he put William Penney, a British professor who had worked in the Manhattan Project, in charge of developing this bomb. In this the test of the Orange Herald was successful.[6]

It is believed by some that the large requirements of tritium that Orange Herald needed (actually it contained only a small amount of thermonuclear material [2]) was a major cause of the Windscale fire. It was unpopular with the scientists who worked on the project. One of the workers in the British nuclear program, Dr. Bryan Taylor, is quoted as saying "I thought that Orange Herald was a stupid device. It wasn't elegant, it couldn't be developed any further, it was a dead end design. And it consumed an enormous amount of very expensive fissile material.".[7] This is the thesis of a BBC documentary on the topic of the fire, Windscale: Britain’s Biggest Nuclear Disaster[8].

See also

- Rainbow Code

- Windscale fire

- Mark 18 nuclear bomb

- Ivy King

Notes

- Arnold & Pyne 2001, pp. 87.

- Arnold & Pyne 2001, pp. 261.

- The Real Meaning of the Words: A Very Pedantic Guide to British Nuclear Weapons Codenames

- British Nuclear Testing, Carey Sublette, at nuclearweaponarchive.org. Accessed 2009-04-28

- "Grapple Series Begins at Christmas Island". AWE. Archived from the original on 23 January 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Fred Pearce (Oct 14, 2017). "Atomic Briton who brought home the bomb". New Scientist.

- Windscale. Britain's biggest nuclear disaster (2007, BBC)

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00825mh

External links

References

- Arnold, Lorna; Pyne, Katherine (2001). Britain and the H-bomb. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-230-59977-2. OCLC 753874620.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)