King Kong vs. Godzilla

King Kong vs. Godzilla (キングコング対ゴジラ, Kingu Kongu tai Gojira) is a 1962 Japanese kaiju monster film directed by Ishirō Honda, with special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya. Produced and distributed by Toho Studios, it is the third film in the Godzilla franchise, and the first of two Toho-produced films featuring King Kong. It is also the first time that both characters appeared on film in color and widescreen.[6] The film stars Tadao Takashima, Kenji Sahara, Yū Fujiki, Ichirō Arishima, and Mie Hama, with Shoichi Hirose as King Kong and Haruo Nakajima as Godzilla. In the film, as Godzilla is reawakened by an American submarine, a pharmaceutical company captures King Kong for promotional uses, which culminates into a battle on Mount Fuji.

| King Kong vs. Godzilla | |

|---|---|

Japanese Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ishirō Honda |

| Produced by | Tomoyuki Tanaka |

| Written by | Shinichi Sekizawa |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Akira Ifukube |

| Cinematography | Hajime Koizumi |

| Edited by | Reiko Kaneko |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese English |

| Budget | $620,000[lower-alpha 1] |

| Box office | $10 million (est.)[lower-alpha 2] |

The project began with a story outline that featured King Kong battling a giant Frankenstein monster, written by Willis H. O'Brien. O'Brien handed the outline to producer John Beck for development. Behind O'Brien's back and without his knowledge, Beck would eventually take the project to Toho to produce the film, replacing the Frankenstein monster with Godzilla and scrapping O'Brien's story.[7]

King Kong vs. Godzilla was released theatrically in Japan on August 11, 1962. The film remains the most attended Godzilla film in Japan to date,[8] and is credited with encouraging Toho to prioritize the continuation of the Godzilla series after seven years of dormancy. A heavily edited version was released by Universal International Inc. theatrically in the United States on June 26, 1963.

Plot

Mr. Tako, head of Pacific Pharmaceuticals, is frustrated with the television shows his company is sponsoring and wants something to boost his ratings. When a doctor tells Tako about a giant monster he discovered on the small Faro Island, Tako believes that it would be a brilliant idea to use the monster to gain publicity. Tako immediately sends two men, Sakurai and Kinsaburo, to find and bring back the monster. Meanwhile, the American submarine Seahawk gets caught in an iceberg. The iceberg collapses, unleashing Godzilla (who, in the Japanese version, had been trapped within since 1955), who then destroys the submarine and a nearby Arctic military base.

On Faro Island, a gigantic octopus crawls ashore and attacks the native village. The mysterious Faro monster, revealed to be King Kong, arrives and defeats the octopus. Kong then drinks some red berry juice that immediately puts him to sleep. Sakurai and Kinsaburo place Kong on a large raft and begin to transport him back to Japan. Mr. Tako arrives on the ship transporting Kong, but a JSDF ship stops them and orders them to return Kong to Faro Island. Meanwhile, Godzilla arrives in Japan and begins terrorizing the countryside. Kong wakes up and breaks free from the raft. Reaching the mainland, Kong confronts Godzilla and proceeds to throw giant rocks at Godzilla. Godzilla is not fazed by King Kong's rock attack and uses its atomic breath to burn him. Kong retreats after realizing that he is not yet ready to take on Godzilla and his atomic breath.

The JSDF digs a large pit laden with explosives and poison gas and lures Godzilla into it, but Godzilla is unharmed. They next string up a barrier of power lines around the city filled with 1,000,000 volts of electricity (50,000 volts were tried in the first film, but failed to turn the monster back), which prove effective against Godzilla. Kong then approaches Tokyo and tears through the power lines, feeding off the electricity, which seems to make him stronger. Kong then enters Tokyo and captures Fumiko, Sakurai's sister. The JSDF launches capsules full of the Faro Island berry juice in gas form, which puts Kong to sleep, and are able to rescue Fumiko. The JSDF then decides to transport Kong via balloons to Godzilla, in hopes that they will kill each other.

The next morning, Kong is dropped next to Godzilla at the summit of Mount Fuji and the two engage in a final battle. Godzilla initially has the advantage due to his atomic breath and nearly kills Kong. After knocking Kong out with a devastating dropkick and tail smacks to the head, Godzilla begins burning the foliage around Kong trying to cremate him. Suddenly a bolt of lightning from thunder clouds strike King Kong reviving him and charging him up. The monsters resume their fight, making their way towards the coastline and destroying Atami Castle before falling off a cliff together into the Pacific Ocean. After an underwater battle, only Kong resurfaces from the water, and he begins to swim back towards his island home. There is no sign of Godzilla, but the JSDF speculates that it is possible that he survived.

Cast

- Tadao Takashima as Osamu Sakurai

- Kenji Sahara as Kazuo Fujita

- Yū Fujiki as Kinsaburo Furue

- Ichirō Arishima as Mr. Tako

- Mie Hama as Fumiko Sakurai

- Jun Tazaki as General Masami Shinzo

- Akiko Wakabayashi as Tamie

- Akihiko Hirata as Shigesawa, Doctor

- Somesho Matsumoto as Onuki, Doctor

- Akemi Negishi as Chikiro's Mother, Faro Island Native

- Senkichi Omura as Konno, TTV Translator

- Sachio Sakai as Obayashi, Mr. Tako's Assistant

- Haruya Kato as Obayashi's Assistant

- Nadao Kirino as General's Aide

- Yoshio Kosugi as Faro Island Chief

- Shin Otomo as Ship Captain

- Harold Conway as Scientist on Submarine

- Shoichi Hirose as King Kong[9]

- Haruo Nakajima as Godzilla[9]

Production

Conception

The film had its roots in an earlier concept for a new King Kong feature developed by Willis O'Brien, animator of the original stop-motion Kong. Around 1960, O'Brien came up with a proposed treatment, King Kong Meets Frankenstein,[10] where Kong would fight against a giant Frankenstein Monster in San Francisco.[11] O'Brien took the project (which consisted of some concept art[12] and a screenplay treatment) to RKO to secure permission to use the King Kong character. During this time, the story was renamed King Kong vs. the Ginko[13] when it was believed that Universal had the rights to the Frankenstein name (it actually only had the rights to the monster's makeup design by Jack Pierce). O'Brien was introduced to producer John Beck, who promised to find a studio to make the film (at this point in time, RKO was no longer a production company). Beck took the story treatment and had George Worthing Yates flesh it out into a screenplay. The story was slightly altered and the title changed to King Kong vs. Prometheus, returning the name to the original Frankenstein concept (The Modern Prometheus was the alternate title of the original novel). Unfortunately, the cost of stop-motion animation discouraged potential studios from putting the film into production. After shopping the script around overseas, Beck eventually attracted the interest of the Japanese studio Toho, which had long wanted to make a King Kong film.[lower-alpha 3] After purchasing the script, they decided to replace the Frankenstein creature with Godzilla to be King Kong's opponent and would have Shinichi Sekizawa rewrite Yates's script. The studio thought that it would be the perfect way to celebrate its 30th year in production.[15] It was one of five big banner releases for the company to celebrate the anniversary alongside Sanjuro, 47 Samurai, Lonely Lane, and Born in Sin.[16] John Beck's dealings with Willis O'Brien's project were done behind his back, and O'Brien was never credited for his idea.[17] Merian C. Cooper was bitterly opposed to the project, stating in a letter addressed to his friend Douglas Burden, "I was indignant when some Japanese company made a belittling thing, to a creative mind, called King Kong vs. Godzilla. I believe they even stooped so low as to use a man in a gorilla suit, which I have spoken out against so often in the early days of King Kong".[18] In 1963, he filed a lawsuit to enjoin distribution of the movie against John Beck, as well as Toho and Universal (the film's U.S. copyright holder) claiming that he outright owned the King Kong character, but the lawsuit never went through, as it turned out he was not Kong's sole legal owner as he had previously believed.[19]

Themes

Ishiro Honda wanted the theme of the movie to be a satire of the television industry in Japan. In April 1962, TV networks and their various sponsors started producing outrageous programming and publicity stunts to grab audiences attention after two elderly viewers reportedly died at home while watching a violent wrestling match on TV.[20] The various rating wars between the networks and banal programming that followed this event caused widespread debate over how TV would effect Japanese culture with Soichi Oya stating TV was creating "a nation of 100 million idiots".[21] Honda stated "People were making a big deal out of ratings, but my own view of TV shows was that they did not take the viewer seriously, that they took the audience for granted....so I decided to show that through my movie"[20] and "the reason I showed the monster battle through the prism of a ratings war was to depict the reality of the times".[22] Honda addressed this by having a pharmaceutical company sponsor a TV show and going to extremes for a publicity stunt for ratings by capturing a giant monster stating "All a medicine company would have to do is just produce good medicines you know? But the company doesn't think that way. They think they will get ahead of their competitors if they use a monster to promote their product.".[23] Honda would work with screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa on developing the story stating that "Back then Sekizawa was working on pop songs and TV shows so he really had a clear insight into television".[24]

Filming

Special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya was planning on working on other projects at this point in time such as a new version of a fairy tale film script called Kaguyahime (Princess Kaguya), but he postponed those to work on this project with Toho instead since he was such a huge fan of King Kong.[25] He stated in an early 1960s interview with the Mainichi Newspaper, "But my movie company has produced a very interesting script that combined King Kong and Godzilla, so I couldn't help working on this instead of my other fantasy films. The script is special to me; it makes me emotional because it was King Kong that got me interested in the world of special photographic techniques when I saw it in 1933."[26]

Eiji Tsuburaya had a stated intention to move the Godzilla series in a lighter direction. This approach was not favoured by most of the effects crew, who "couldn't believe" some of the things Tsuburaya asked them to do, such as Kong and Godzilla volleying a giant boulder back and forth. But Tsuburaya wanted to appeal to children's sensibilities and broaden the genre's audience.[27] This approach was favoured by Toho and to this end, King Kong vs. Godzilla has a much lighter tone than the previous two Godzilla films and contains a great deal of humor within the action sequences. With the exception of the next film, Mothra vs. Godzilla, this film began the trend to portray Godzilla and the monsters with more and more anthropomorphism as the series progressed, to appeal more to younger children. Ishirō Honda was not a fan of the dumbing down of the monsters.[23] Years later, Honda stated in an interview. "I don't think a monster should ever be a comical character." "The public is more entertained when the great King Kong strikes fear into the hearts of the little characters."[1][28] The decision was also taken to shoot the film in a (2.35:1) scope ratio (Tohoscope) and to film in color (Eastman Color), marking both monsters' first widescreen and color portrayals.[29] Additionally, the theatrical release was accompanied by both a true 4.0 stereophonic soundtrack, and a regular monaural mix.

Toho had planned to shoot this film on location in Sri Lanka, but had to forgo that (and scale back on production costs) because it ended up paying RKO roughly ¥80 million ($220,000) for the rights to the King Kong character.[16] The bulk of the film was shot on Izu Ōshima (an island near Japan) instead.[30] The movie's production budget came out to ¥150 million[1][2] ($420,000).[3]

Suit actors Shoichi Hirose (King Kong) and Haruo Nakajima (Godzilla) were given mostly free rein by Eiji Tsuburaya to choreograph their own moves. The men would rehearse for hours and would base their moves on that from professional wrestling (a sport that was growing in popularity in Japan),[31] in particular the movies of Toyonobori.[32]

During pre-production, Eiji Tsuburaya had toyed with the idea of using Willis O'Brien's stop-motion technique instead of the suitmation process used in the first two Godzilla films, but budgetary concerns prevented him from using the process, and the more cost efficient suitmation was used instead. However, some brief stop motion was used in a couple of quick sequences. One of these sequences was animated by Koichi Takano[33] who was a member of Eiji Tsuburaya's crew.

A brand new Godzilla suit was designed for this film and some slight alterations were done to its overall appearance. These alterations included the removal of its tiny ears, three toes on each foot rather than four, enlarged central dorsal fins and a bulkier body. These new features gave Godzilla a more reptilian/dinosaurian appearance.[34] Outside of the suit, a meter high model and a small puppet were also built. Another puppet (from the waist up) was also designed that had a nozzle in the mouth to spray out liquid mist simulating Godzilla's atomic breath. However the shots in the film where this prop was employed (far away shots of Godzilla breathing its atomic breath during its attack on the Arctic Military base) were ultimately cut from the film.[35] These cut scenes can be seen in the Japanese theatrical trailer.[36] Finally, a separate prop of Godzilla's tail was also built for close up practical shots when its tail would be used (such as the scene where Godzilla trips Kong with its tail). The tail prop would be swung offscreen by a stage hand.[35]

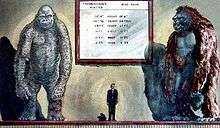

Sadamasa Arikawa (who worked with Eiji Tsuburaya) said that the sculptors had a hard time coming up with a King Kong suit that appeased Tsuburaya.[27] The first suit was rejected for being too fat with long legs giving Kong what the crew considered an almost cute look.[27] A few other designs were done before Tsuburaya would approve the final look that was ultimately used in the film. The suit's body design was a team effort by brothers Koei Yagi and Kanji Yagi and was covered with expensive yak hair, which Eizo Kaimai hand-dyed brown.[37] Because RKO instructed that the face must be different from the original's design, sculptor Teizo Toshimitsu based Kong's face on the Japanese macaque rather than a gorilla, and designed two separate masks.[37] As well, two separate pairs of arms were also created. One pair were extended arms that were operated by poles inside the suit to better give Kong a gorilla-like illusion, while the other pair were at normal arms length and featured gloves that were used for scenes that required Kong to grab items and wrestle with Godzilla.[38] Suit actor Hirose had to be sewn into the suit in order to hide the zipper. This would force him to be trapped inside the suit for large amounts of time and would cause him much physical discomfort. In the scene where Kong drinks the berry juice and falls asleep, he was trapped in the suit for three hours. Hirose stated in an interview "Sweat came pouring out like a flood and it got into my eyes too. When I came out, I was pale all over".[39] Besides the suit with the two separate arm attachments, a meter high model and a puppet of Kong (used for closeups) were also built.[40][41] As well, a huge prop of Kong's hand was built for the scene where he grabs Mie Hama (Fumiko) and carries her off.[42][43]

For the attack of the giant octopus, four live octopuses were used. They were forced to move among the miniature huts by having hot air blown onto them. After the filming of that scene was finished, three of the four octopuses were released. The fourth became special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya's dinner. These sequences were filmed on a miniature set outdoors on the Miura Coast.[44] Along with the live animals, two rubber octopus props were built, with the larger one being covered with plastic wrap to simulate mucous. Some stop-motion tentacles were also created for the scene where the octopus grabs a native and tosses him.[45] These sequences were shot indoors at Toho Studios.[44]

Since King Kong was seen as the bigger draw[46] and since Godzilla was still a villain at this point in the series, the decision was made to not only give King Kong top billing but also to present him as the winner of the climactic fight. While the ending of the film does look somewhat ambiguous, Toho confirmed that King Kong was indeed the winner in their 1962–63 English-language film program Toho Films Vol. 8,[47] which states in the film's plot synopsis, A spectacular duel is arranged on the summit of Mt. Fuji and King Kong is victorious. But after he has won...[48]

English version

When John Beck sold the King Kong vs. Prometheus script to Toho (which became King Kong vs. Godzilla), he was given exclusive rights to produce a version of the film for release in non-Asian territories. He was able to line up a couple of potential distributors in Warner Bros. and Universal-International even before the film began production. Beck, accompanied by two Warner Bros. representatives, attended at least two private screenings of the film on the Toho Studios lot before it was released in Japan.[4]

John Beck enlisted the help of two Hollywood writers, Paul Mason and Bruce Howard, to write a new screenplay. After discussions with Beck, the two wrote the American version and worked with editor Peter Zinner to remove scenes, recut others, and change the sequence of several events. To give the film more of an American feel, Mason and Howard decided to insert new footage that would convey the impression that the film was actually a newscast. The television actor Michael Keith played newscaster Eric Carter, a United Nations reporter who spends much of the time commenting on the action from the U.N. Headquarters via an International Communications Satellite (ICS) broadcast. Harry Holcombe was cast as Dr. Arnold Johnson, the head of the Museum of Natural History in New York City, who tries to explain Godzilla's origin and his and Kong's motivations.[49][50] The new footage, directed by Thomas Montgomery, was shot in three days.[51]

Beck and his crew were able to obtain library music from a host of older films (music tracks that had been composed by Henry Mancini, Hans J. Salter, and even a track from Heinz Roemheld). These films include Creature from the Black Lagoon, Bend of the River, Untamed Frontier, The Golden Horde, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, Man Made Monster, Thunder on the Hill, While the City Sleeps, Against All Flags, The Monster That Challenged the World, The Deerslayer and music from the TV series Wichita Town. Cues from these scores were used to almost completely replace the original Japanese score by Akira Ifukube and give the film a more Western sound.[52] They also obtained stock footage from the film The Mysterians from RKO (the film's US copyright holder at the time) which was used to not only represent the ICS, but which was also utilized during the film's climax.[53] Stock footage of a massive earthquake from The Mysterians was employed to make the earthquake caused by Kong and Godzilla's plummet into the ocean much more violent than the tame tremor seen in the Japanese version. This added footage features massive tidal waves, flooded valleys, and the ground splitting open swallowing up various huts.[53]

Beck spent roughly $15,500 making his English version and sold the film to Universal-International for roughly $200,000 on April 29, 1963.[4] The film opened in New York on June 26 of that year.[4]

Starting in 1963, Toho's international sales booklets began advertising an English dub of King Kong vs. Godzilla alongside Toho-commissioned, uncut international dubs of movies such as Giant Monster Varan and The Last War. By association, it is thought that this King Kong vs. Godzilla dub is an uncut, English-language international version not known to have been released on home video.[54]

Release

Theatrical

.png)

In Japan, the film first released on August 11, 1962.[55] The film was re-released twice as part of the Champion Matsuri (東宝チャンピオンまつり),[56] a film festival that ran from 1969 through 1978 that featured numerous films packaged together and aimed at children, first in 1970,[57] and then again in 1977,[58] to coincide with the Japanese release of King Kong.[59]

After its theatrical re-releases, the film was screened two more times at specialty festivals. In 1979, to celebrate Godzilla's 25th anniversary, the film was reissued as part of a triple bill festival known as The Godzilla Movie Collection (Gojira Eiga Zenshu). It played alongside Invasion of Astro-Monster and Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla.[60] This release is known among fans for its exciting and dynamic movie poster featuring all the main kaiju from these three films engaged in battle.[61] Then in 1983, the film was screened as part of The Godzilla Resurrection Festival (Gojira no Fukkatsu). This large festival featured 10 Godzilla/kaiju films in all (Godzilla, King Kong vs. Godzilla, Mothra vs. Godzilla, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, Invasion of Astro-Monster, Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, Rodan, Mothra, Atragon, and King Kong Escapes).[62]

In North America, King Kong vs. Godzilla premiered in New York City on June 26, 1963.[5] The film was also released in many international markets. In Germany, it was known as Die Rückkehr des King Kong ("The Return of King Kong") and in Italy as Il trionfo di King Kong ("The triumph of King Kong").[63][64] In France, it was released as King Kong contre Godzilla (analogous to the English-language title) in 1976.[65]

Home media

The Japanese version of this film was released numerous times through the years by Toho on different home video formats.[66] The film was first released on VHS in 1985 and again in 1991. It was released on LaserDisc in 1986 and 1991, and then again in 1992 in its truncated 74-minute form as part of a laserdisc box set called the Godzilla Toho Champion Matsuri. Toho then released the film on DVD in 2001. They released it again in 2005 as part of the Godzilla Final Box DVD set,[67] and again in 2010 as part of the Toho Tokusatsu DVD Collection. This release was volume #8 of the series and came packaged with a collectible magazine that featured stills, behind the scenes photos, interviews, and more. In the summer of 2014, the film was released for the first time on Blu-ray as part of the company releasing the entire series on the Blu-Ray format for Godzilla's 60th anniversary.[68]

The American version was released on VHS by GoodTimes Entertainment (which acquired the license of some of Universal's film catalogue) in 1987, and then on DVD to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the film's U.S release in 1998. Both of these releases were full frame. Universal Pictures released the English-language version of the film on DVD in widescreen as part of a two-pack bundle with King Kong Escapes in 2005,[67] and then on its own as an individual release on September 15, 2009. They then re-released the film on Blu-Ray on April 1, 2014, along with King Kong Escapes.[69] This release sold $749,747 worth of Blu-Rays.[70] FYE released an exclusive Limited Edition Steelbook version of this Blu-ray on September 10, 2019.

In 2019, the Japanese and American versions were included in a Blu-ray box set released by the Criterion Collection, which included all 15 films from the franchise's Shōwa era.[71]

Box office

In Japan, this film has the highest box office attendance figures of all of the Godzilla films to date. It sold 11.2 million tickets during its initial theatrical run, accumulating ¥352 million in distribution rental earnings.[72][2] The film was the fourth highest-grossing film in Japan that year behind The Great Wall (Shin no shikōtei), Sanjuro, and 47 Samurai and was Toho's second biggest moneymaker.[73] At an average 1962 Japanese ticket price, 11.2 million ticket sales were equivalent to estimated gross receipts of approximately ¥1.29 billion[74] ($3.58 million).[3]

Including re-releases, the film accumulated a lifetime figure of 12.6 million tickets sold in Japan,[75] with distribution rental earnings of ¥430 million.[76][77] The 1970 re-release sold 870,000 tickets,[55] equivalent to estimated gross receipts of approximately ¥280 million[74] ($780,000).[3] The 1977 re-release sold 480,000 tickets,[55] equivalent to estimated gross receipts of approximately ¥440 million[74] ($1.64 million).[3] This adds up to total estimated Japanese gross receipts of approximately ¥2 billion ($6 million).

In the United States, the film grossed $2.7 million,[5] accumulating a profit (via rentals) of $1.25 million.[78] In France, where it released in 1976, the film sold 554,695 tickets,[65] equivalent to estimated gross receipts of approximately €1,497,680[79] ($1,667,650).[80] This adds up to total estimated gross receipts of approximately $10,367,650 worldwide.

Adjusted for inflation, 12.6 million Japanese ticket sales are equivalent to $223 million at an average 2014 Japanese ticket price, while 554,695 French ticket sales are equivalent to $6.8 million at an average 2014 French ticket price.[81] $2.7 million at 1963 US ticket prices are equivalent to $30 million at an average 2020 US ticket price.[82] This adds up to an estimated inflation-adjusted gross of approximately $260 million worldwide.

Preservation

The original Japanese version of King Kong vs. Godzilla is infamous for being one of the most poorly-preserved tokusatsu films. In 1970, director Ishiro Honda prepared an edited version of the film for the Toho Champion Festival, a children's matinee program that showcased edited re-releases of older kaiju films along with cartoons and then-new kaiju films. Honda cut 24 minutes from the film's original negative and, as a result, the highest quality source for the cut footage was lost. For years, all that was thought to remain of the uncut 1962 version was a faded, heavily damaged 16mm element from which rental prints had been made. 1980s restorations for home video integrated the 16mm deleted scenes into the 35mm Champion cut, resulting in wildly inconsistent picture quality.[83]

In 1991, Toho issued a restored laserdisc incorporating the rediscovery of a reel of 35mm trims of the deleted footage. The resultant quality was far superior to previous reconstructions, but not perfect; an abrupt cut caused by missing frames at the beginning or end of a trim is evident whenever the master switches between the Champion cut and a 35mm trim within the same shot. This laserdisc master was utilized for Toho's 2001 DVD release with few changes.[67]

In 2014, Toho released a new restoration of the film on Blu-Ray, which utilized the 35mm edits once again, but only those available for reels 2-7 of the film were able to be located. The remainder of video for the deleted portions was sourced from the earlier Blu-Ray of the U.S. version, in addition to the previous 480i 1991 laserdisc master.[67] On July 14, 2016, a 4K restoration of a completely 35mm sourced version of the film aired on The Godzilla First Impact,[84][85] a series of 4K broadcasts of Godzilla films on the Nihon Eiga Senmon Channel.[86]

Legacy

Due to the film's great box office success, Toho planned to produce a sequel almost immediately. The sequel was simply called Continuation: King Kong vs. Godzilla.[87][88] However the project was ultimately cancelled.[89]

Also due to the great box office success of this film, Toho was convinced to build a franchise around the character of Godzilla and started producing sequels on a yearly basis.[90] The next project was to pit Godzilla against another famous movie monster icon: a giant Frankenstein Monster. In 1963, Kaoru Mabuchi (a.k.a. Takeshi Kimura) wrote a script called Frankenshutain tai Gojira.[91] Ultimately, Toho rejected the script and the next year pitted Mothra against Godzilla instead in the 1964 film Mothra vs. Godzilla. This began an intra-company style crossover where kaiju from other Toho kaiju films would be brought into the Godzilla series.

Toho was eager to build a series around their version of King Kong, but were refused by RKO.[92] They worked with the character again in 1967 though, when they helped Rankin/Bass co produce their film King Kong Escapes (which was loosely based on a cartoon series R/B had produced). That film, however, was not a sequel to King Kong vs. Godzilla.

Henry G. Saperstein (whose company UPA co-produced the 1965 film Frankenstein vs. Baragon (a.k.a. Frankenstein Conquers the World in the U.S.) and the 1966 sequel film The War of the Gargantuas with Toho) was so impressed with the octopus sequence[93] that he requested the creature to appear in these two productions. The giant octopus appeared in an alternate ending in Frankenstein Conquers the World that was intended specifically for the American market, but was ultimately never used.[91] The creature did reappear at the beginning of the film's sequel The War of the Gargantuas this time being retained in the finished film.[94]

Even though it was only featured in this one film (although it was used for a couple of brief shots in Mothra vs. Godzilla[95]), this Godzilla suit was always one of the more popular designs among fans from both sides of the Pacific. It formed the basis for some early merchandise in the U.S. in the 1960s, such as a popular model kit by Aurora Plastics Corporation, and a popular board game by Ideal Toys.[96] This game was released alongside a King Kong game in 1963[97] to coincide with the U.S. theatrical release of the film.

The King Kong suit from this film was redressed into the giant monkey Goro for episode 2 (GORO and Goro) of the television show Ultra Q.[98] Afterwards, it was reused for the water scenes (although it was given a new mask/head) for King Kong Escapes.[99] Scenes of the giant octopus attack were reused in black and white for episode 23 (Fury of the South Seas) of Ultra Q.[98]

In 1992 (to coincide with the company's 60th anniversary), Toho wanted to remake this film as Godzilla vs. King Kong [100] as part of the Heisei series of Godzilla films. However, according to the late Tomoyuki Tanaka, it proved to be difficult to obtain permission to use King Kong.[101] Next, Toho thought to make Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong[102] but, (according to Koichi Kawakita), it was discovered that obtaining permission even to use the likeness of King Kong would be difficult.[103][104] Mechani-Kong was replaced by Mechagodzilla, and the project eventually evolved into Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II in 1993.

In making Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, the special effects crew was instructed to watch the giant octopus scene to get reference for the Kraken.[105]

Through the years, the film has been referenced in various songs, advertising, television shows and comic books. It was referenced in Da Lench Mob's 1992 single "Guerillas in tha Mist".[106] It was spoofed in advertising for a Bembos burger commercial from Peru,[107] for Ridsect Lizard Repellant,[108] and for the board game Connect 4.[109] It was paid homage to in comic books by DC Comics,[110] Bongo Comics,[111] and Disney Comics.[112] It was even spoofed in The Simpsons episode "Wedding for Disaster".

In 2015, Legendary Entertainment announced plans for a Godzilla vs. Kong film of their own (unrelated to Toho's version), to be released on May 21, 2021.[113]

Dual ending myth

For many years, a popular myth has persisted that in the Japanese version of this film, Godzilla emerges as the winner. The myth originated in the pages of Spacemen magazine, a 1960s sister magazine to the influential publication Famous Monsters of Filmland. In an article about the film, it is incorrectly stated that there were two endings and "If you see King Kong vs Godzilla in Japan, Hong Kong or some Oriental sector of the world, Godzilla wins!"[114] The article was reprinted in various issues of Famous Monsters of Filmland in the years following, such as in issues #51 and #114. This misinformation would be accepted as fact[115] and persist for decades. For example, a question in the "Genus III" edition of the popular board game Trivial Pursuit asked, "Who wins in the Japanese version of King Kong vs. Godzilla?" and stated that the correct answer was "Godzilla". Various media have repeated this falsehood,[116] including the Los Angeles Times.[4]

But with the rise of home video, Westerners have increasingly been able to view the original version and the myth has been dispelled. The only differences between the two endings of the film are minor:

- In the Japanese version, as Kong and Godzilla are fighting underwater, a very small earthquake occurs. In the American version, producer John Beck used stock footage of a violent earthquake from the 1957 Toho film The Mysterians to make the climactic earthquake seem far more violent and destructive.

- The dialogue is slightly different. In the Japanese version, onlookers are wondering if Godzilla might be dead or not as they watch Kong swim home and speculate that it is possible he survived. In the American version, onlookers simply say, "Godzilla has disappeared without a trace" and newly shot scenes of reporter Eric Carter have him watching Kong swim home on a view screen and wishing him luck on his long journey home.

- As the film ends and the screen fades to black, "Owari" ("The End") appears onscreen. Godzilla's roar, followed by Kong's, is on the Japanese soundtrack. This was akin to the monsters' taking a bow or saying goodbye to the audience, as at this point the film is over. In the American version, only Kong's roar is present on the soundtrack.

In 1993, comic book artist Arthur Adams wrote and drew a one-page story that appeared in the anthology Urban Legends #1, published by Dark Horse Comics, which dispels the popular misconception about the two versions of King Kong vs. Godzilla.[117]

See also

Notes

- The Japanese version cost ¥150 million[1][2] ($420,000).[3] The American version cost a further $200,000.[4]

- Estimated box office gross receipts (including re-releases) were approximately $6 million in Japan and $1,667,650 in France (see Box office section). In the United States, it grossed $2.7 million during its theatrical run.[5] This adds up to an estimated total gross of approximately $10,367,650 worldwide.

- According to Teruyoshi Nakano, Tomoyuki Tanaka and Eiji Tsuburaya wanted to make a King Kong film for Toho as early as 1954 because he was "world famous".[14]

References

- Brothers 2009, pp. 47–48.

- Takeuchi Hiroshi. The Complete Works of Ishiro Honda (本多猪四郎全仕事). Asahi Sonorama. 2000. Pgs. 27-28

- "Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average) - Japan". World Bank. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Ryfle 1998, pp. 87–90.

- Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 191.

- Twenty-five Years with Godzilla by Ed Godziszewski. Fangoria #1. O'Quinn Studios Inc., 1979. Pg. 35

- Ryfle 1998, p. 80-81.

- "King Kong vs Godzilla from Nihon-Eiga" (in Japanese). Nihon Eiga Broadcasting Corp. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 353.

- Cotta Vaz 2005, p. 361.

- Steve Archer. Willis O'Brien: Special Effects Genius. Mcfarland, 1993. pp. 80–83.

- "The 13 Faces of Frankenstein" by Forrest J Ackerman. Famous Monsters of Filmland #39. Warren Publishing. 1966. Pgs. 58-60

- Donald F. Glut. The Frankenstein Legend: A Tribute to Mary Shelley and Boris Karloff. Scarecrow Press, 1973. Pgs. 242-244

- Information Explosion. Teruyoshi Nakano talks of Godzilla past, present, and future. G-Fan #71. Daikaiju Enterprises, 2005. Pgs. 53-54

- Paul A. Woods. King Kong Cometh! Plexus Publishing Limited, 2005. Pg. 119

- Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 186.

- Willis O'Brien-Creator of the Impossible by Don Shay. Cinefex #7 R.B Graphics. 1982. Pgs. 69-70

- L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Brigham Young University. Cooper Papers. Box MSS 2008 Box 8 Folder 6

- Cotta Vaz 2005, pp. 361–363.

- Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 185.

- Jayson Makoto Chun. A Nation of a Hundred Million Idiots?: A Social History of Japanese Television, 1953 - 1973. Routlegde. 2006

- Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 187.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 82.

- Toho Company Limited. King Kong vs. Godzilla / Earth Defense Army (Toho SF Sci-Fi Film Series (Vol.5)) (東宝 東宝SF特撮映画シリーズ 5 キングコング対ゴジラ/地球防衛). Toho Publishing Company Limited. 1986

- Kobayashi Tatsuyoshi & Nomoto Samurai.Eiji Tsuburaya: The Film Director Who Made Ultraman(円谷英二 : ウルトラマンをつくった映画監督).Shogakkan Publishing.1996. Pgs.48-53.

- A Walk Through Monster Films of the Past by Hiroshi Takeuchi. Markalite-The Magazine of Japanese Fantasy #3. Pacific Rim Publishing Company. 1991. Pgs. 56-57

- Kabushiki 1993, pp. 115–123.

- Ishiro Honda & Yoshikazu Masuda. Ishiro Honda-Godzilla And My Movie Life (「ゴジラ」とわが映画人生). Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha. 1994. Pgs. 62-63

- We Love Godzilla Everytime (僕たちの愛した怪獣ゴジラ). Gakken Graphic Books. 1996. Pgs. 24-25

- Stuart Galbraith IV. Monsters are Attacking Tokyo! Feral House, 1998. Pgs. 83-84

- Ragone 2014, p. 70.

- Japan's Kong-Nection How O'Brien's Eighth Wonder of the World inspired Tsuburaya's Kingdom of Giant Monsters by Jim Cirronella. Famous Monsters of Filmland #267. Movieland Classics LLC. May/Jun 2013. Pg.68

- "Koichi Takano memoriam on SciFiJapan".

- Sho Motoyama & Rieko Tsuchiya. Godzilla Museum Book. ASCII Publishing, 1994.

- Kaneko & Nakajima 1983, p. 103.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 84.

- Toho Company Limited. Toho Special Effects Movie Complete Works (東宝特撮映画大全集 Tōhō Tokusatsu Eiga Taizenshū). Village Books. 2012. Pgs. 66-69.

- Masami Yamada. The Pictorial Book of Godzilla Vol. 2. Hobby Japan Co, Ltd. 1995. Pgs. 46-47

- Guy Mariner Tucker. Age of the Gods: A history of the Japanese fantasy film. Daikaiju Publishing, 1996.

- Kaneko & Nakajima 1983, p. 67.

- Kishikawa 1994, p. 62.

- Kishikawa 1994, p. 63.

- We Love Godzilla Everytime Encyclopedia. Gakken Graphic Books. 1996. Pg. 25.

- Osamu Kishikawa. Toho SFX Movies Authentic Visual Book Vol.51 Giant Octopus (1962-1966)(東宝特撮 公式ヴィジュアル・ブック Vol. 51 大ダコ1962-1966 Tōhō Tokusatsu Kōshiki Vijuaru Bukku Vol.51 Ōdako 1962-1966). Dai Nippon Printing. 2020. p.2

- Masami Yamada. Pg. 48

- When We Were Kings by Steve Ryfle. Famous Monsters of Filmland #287. Movieland Classics LLC, 2016. Pg. 36

- "Toho Films Vol 8".

- "Toho Company Limited. Toho Films Vol.8. Toho Publishing Co. Ltd, 1963. Pg. 9".

- The Legend of Godzilla-Part One by August Ragone and Guy Tucker. Markalite: The Magazine of Japanese Fantasy #3. Pacific Rim Publishing Company, 1991. Pg. 27

- "Interview: KING KONG VS GODZILLA Screenwriter Paul Mason".

- "Kaijuphile Movie Reviews : King Kong vs. Godzilla". Kaijuphile.com. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- War of the Titans (Liner notes) by David Hirsch. King Kong vs Godzilla: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. La-La Land Records, 2005. Pgs. 4-9

- Ryfle 1998, p. 90.

- "Toho Films Vol. 8, 1963, Pg. 62".

- "King Kong vs Godzilla Box Office". Toho Kingdom. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- "Toho Champion Festival".

- 様々な著者Godzilla Toho Champion Matsuri Perfection (ゴジラが「僕らのヒーロー」だった時代!). ASCII Media Works/Dengeki Hobby Books. 2014. Pgs.32-33

- ゴジラが「僕らのヒーロー」だった時代! Pgs.63-64

- Closeup: Far East Report by Greg Shoemaker. Japanese Fantasy Film Journal #12. JFFJ Publishing. 1979. Pg.23

- "Gojira Eiga Zenshu".

- "Gojira Eiga Zenshu film poster" (PDF).

- "Gojira no Fukkatsu Retrospective".

- Godzilla Abroad by J.D Lees. G-Fan #22. Daikaiju Enterprises, 1996. Pgs. 20-21

- "Scans of King Kong vs Godzilla theatrical posters".

- "King Kong vs Godzilla (1976)". JP's Box-Office. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- "King Kong vs Godzilla detailed history of home release formats". Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- "Complete list of home video releases for King Kong vs Godzilla" (in Japanese). LD DVD & Blu-ray. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017.

- "60th Anniversary Edition Godzilla series on Blu-Ray". Archived from the original on March 6, 2014.

- "King Kong vs. Godzilla and King Kong Escapes on Blu-ray from Universal".

- "Kingu Kongu tai Gojira (1962) Home Market Performance". The-Numbers. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Patches, Matt (July 25, 2019). "Criterion reveals the collection's 1000th disc: the ultimate Godzilla set". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Brothers 2009, p. 14.

- Galbraith IV 2008, p. 194.

- "Statistics of Film Industry in Japan". Eiren. Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Goozner, Merrill (August 28, 1994). "Fire-Breathing Godzilla Blowing Out 40 Candles". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "「キングコング対ゴジラ」 KING KONG VS. GODZILLA". G本情報 - ゴジラ王国. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- Candelaria, Matthew (February 11, 2020). "Godzilla Vs Kong: 10 Gonzo Facts About The Original". Screen Rant. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "Top Rental Features of 1963", Variety, January 8, 1964 p 71.

- "Cinema market". Cinema, TV and radio in the EU: Statistics on audiovisual services (Data 1980-2002). Europa (2003 ed.). Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 2003. pp. 31–64 (61). ISBN 92-894-5709-0. ISSN 1725-4515. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Historical currency converter with official exchange rates (EUR)". fxtop.com. December 31, 1978. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Cinema ticket price". NationMaster. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Box Office Mojo by IMDbPro FAQ (How are grosses adjusted for ticket price inflation?)". IMDb. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 86.

- "Nihon Eiga Senmon Schedule". nihon-eiga.com. May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ""King Kong vs Godzilla" 4K advertisement". Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- "4K Remastering Of "King Kong vs. Godzilla" Premiering During Satellite Cable Retrospective". May 3, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "Continuation King Kong vs Godzilla Story Translation".

- ゴジラ 東宝特撮未発表資料アーカイヴ プロデューサー・田中友幸とその時代(Godzilla Toho Special Effects Unpublished Material Archive: Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka and His Era), Kadokawa Group Publishing. 2010.

- The Monsterous History of King Kong vs Godzilla by Insha Fitzpatrick. Birth.Movies.Death Giant Monsters Commemorative Issue, Alamo Drafthouse. 2017. Pg.62

- "Giving Thanks for King Kong vs. Godzilla (You're Welcome)". TCM.

- "Frankenstein vs. the Giant Devilfish".

- Ray Morton, King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon, Applause Theater and Cinema Books. 2005. Pgs. 134-135

- Memories of Ishiro Honda: Twenty years after the passing of Godzilla's famed director by Hajime Ishida. Famous Monsters of Filmland #269, Movieland Classics, LLC. Sept/Oct 2013. Pg. 21

- Katusnobu Higashino. Toho Kaijuu Gurafitii (Toho Monster Graffiti), Kindai Eigasha. 1991. Pgs. 35-37

- "Evolution of Godzilla". Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- "Board Game Geek Godzilla".

- "Board Game Geek King Kong".

- "The Q-Files". Archived from the original on May 16, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- Ragone 2014, p. 165.

- "Godzilla vs. King Kong". Archived from the original on November 21, 2006.

- Toho Company Limited, Toho Sf Special Effects Movie Series Vol 8: Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla, Toho Publishing Products Division, 1993

- "Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong". Archived from the original on November 21, 2006.

- Koichi Kawakita interview by David Milner, Cult Movies #14, Wack "O" Publishing, 1995

- "Koichi Kawakita Interview". Archived from the original on July 26, 2011.

- "Behind the Scenes of the Pirates of the Caribbean Movies".

- "Rapgenius".

- "King Kong and Godzilla Bembos Burger Commercial".

- "Raja Kong vs Lidzilla Ridsect Lizard Repellant Commercial".

- "1990's Connect Four Commercial".

- "Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen #84".

- "Simpsons Comics Presents Bart Simpson #61".

- "Comic Zone #2".

- McClintock, Pamela (June 12, 2020). "'Godzilla vs. Kong' Shifts to 2021; 'Matrix 4' Moves Nearly a Year to 2022". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Return of Kong by Forrest J Ackerman. Spacemen #7. Warren Publishing, 1963. Pgs. 52-56

- Ian Thorne. Godzilla. Crestwood House, 1977. Pg.31

- "Bob Costas misreporting dual ending myth".

- "Arthur Adams Urban Legends".

Bibliography

- Brothers, Peter H. (2009). Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. Author House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cotta Vaz, Mark (2005). Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong. Villiard. ISBN 9781400062768.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461673743.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kabushiki, Gaisha (1993). Gojira Eiga 40-Nenshi, Gojira Deizu (Godzilla Days: 40 years of Godzilla Movies). Shueisha.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaneko, Masumi; Nakajima, Shinsuke (1983). Gojira Mook (Godzilla Graph Book). Kondansya Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kishikawa, Osamu (1994). Godzilla Second 1962-1964. Dai Nippon Kaiga Co, Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ragone, August (2014). Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6078-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-348-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2017). Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819570871.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: King Kong vs. Godzilla |

- キングコング対ゴジラ - Toho's official page for the film

- King Kong vs. Godzilla on IMDb

- King Kong vs. Godzilla at Rotten Tomatoes

- King Kong vs. Godzilla at Movie-Censorship - Detailed comparison between the Japanese and American versions of the film.

- Archer, Eugene. "King Kong vs. Godzilla" (film review) The New York Times. June 27, 1963.

- "キングコング対ゴジラ (Kingu Kongu tai Gojira)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved July 16, 2007.