Onufry Zagłoba

Jan Onufry Zagłoba is a fictional character in the Trilogy by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Together with other characters of The Trilogy, Zagłoba engages in various adventures, fighting for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and seeking adventures and glory. Zagłoba is seen as one of Sienkiewicz most popular and significant characters. While he has often been compared to Shakespearean character of Falstaff, he also goes through extensive character development, becoming a jovial and cunning hero.

| Jan Onufry Zagłoba | |

|---|---|

| The Trilogy character | |

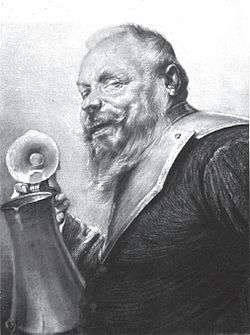

"Pan Zagłoba", by Piotr Stachiewicz | |

| First appearance | With Fire and Sword |

| Last appearance | Fire in the Steppe |

| Created by | Henryk Sienkiewicz |

| Portrayed by | Mieczysław Pawlikowski (Colonel Wolodyjowski)

Kazimierz Wichniarz (The Deluge) Krzysztof Kowalewski (With Fire and Sword) |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Unknown |

| Religion | Christian |

| Nationality | Pole |

Fictional character biography

After meeting another character of the Trilogy, Jan Skrzetuski, Zagłoba, until now living a meaningless life of a lesser noble, trying to survive by exploiting the good faith of others, becomes drawn into the company of hero-like personas, and slowly changes, to become worthy of their trust and friendship.[1][2] Together with them, Zagłoba engages in various adventures, fighting for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and seeking adventures and glory.[3] During a feast, in a rather drunken state, he was the first to call prince Janusz Radziwiłł a traitor.[4] Eventually he becomes a widely known person, treated with respect by powerful magnates and offering counsel to the king.[1] He was balding and half-blind, known for his love of drinking and story-telling (usually glorifying his own exploits), tendency to poke fun at everyone and everything, later also renowned as a cunning tactician.[4]

Significance and literary analysis

Zagłoba appears in Sienkiewicz's The Trilogy series of three books:[3] With Fire and Sword (Ogniem i Mieczem) and The Deluge (Potop), and the last part of the series, Colonel Wolodyjowski (Pan Wołodyjowski).'[4]

Stanisław Kozłowsk notes that Zagłoba is seen as one of Sienkiewicz most popular and significant characters.[1] Roman Dyboski wrote that Zagłoba's humorous persona was one of the most enduring of Sienkiewicz characters.[5] Horst Frenz wrote that Zagłoba "belongs forever to the gallery of immortal comic characters of world literature, and he is thoroughly original."[6]

He has been often compared to the Shakespearean character of Falstaff. This comparison, made by Dyboski[5] and others,[3][7] is often based on his propensity for drinking and partying, sharp tongue and cunning, cowardice, and telling exaggerated tales of his youthful adventures.[1] Unlike Falstaff, he grows to become a more mature character, and this transformation can be observed in the first book, beginning with the moment where he decides to risk his life to protect the proverbial damsel in distress, Helena, in the midst of the ongoing Chmielnicki uprising.[1][2] This transformation is likely the most crucial difference between Zagłoba and Falstaff.[6] Sienkiewicz himself wrote about Zagłoba and Falstaff thus:[7]

"I think Zagłoba is a better character than Falstaff. At heart the old noble was a good fellow. He would fight bravely when it became necessary, where Shakespeare makes Falstaff a coward and a poltroon.

William Lyon Phelps notes that if Zagłoba is a copy of Falstaff, he is as good as the original, a feat he applauds Sienkiewicz for.[8] Edward Bolland Osborn notes he is too complex to be compared to only one character, and has a qualities of many, preferring to describe him as a caricature "of the Polish character in the last days of the chevalerie, when the sabre was still the final argument and [Poland] was the chief bulwark of the Christendom against the vast armies of [the Turks].".[9] In political views, Zagłoba is a model petty Polish noble from the times of sejmik-dominated Polish politics, a rather intolerant Catholic, vocal supporter of sarmatism values such as Golden Freedoms and liberum veto, seeing the noble class as superior to others.[1]

Another character Zagłoba has been compared to is Odysseus (Ulysses), due to their cunning mind, always full of plans and strategies.[1][6][9] He has also been compared to a number of other characters, such as Thersites[9] or the main character of the Roman play Miles Gloriosus (The Swaggering Soldier").[4]

Stanisław Kozłowski notes that the good-natured and light-hearted portrayal of Zagłoba is used by Sienkiewicz to counterbalance the dark setting of the stories, set during the time of war and devastation.[1] He is the symbol of undying optimism and hope, and a strategist who can find his way out of trouble.[2] He is often considered both a comic figure as well as the patriotic hero, even if the latter more often comes from the necessity of the moment.[2] He is respected for his ideas, intelligence and a sharp tongue. For example, when Swedish king Charles X Gustav promised to give Jan Zamoyski Lublin Voivodeship in hereditary possession for opening the gates of Zamość Zagłoba asked Jan to promise in return that he would give the Swedish king the province of Netherlands in exchange which Jan passed in Latin to a Swedish deputy. Everyone who heard that laughed at the Swedish king.

Zagłoba's enduring influence on Polish culture can be seen for example in his appearance in a 2000 Polish television advertisement for the Okocim brewery.[10]

Zagłoba in film and television

- 1914 - Obrona Częstochowy (dir. Edward Puchalski) - portrayed by Aleksander Zelwerowicz

- 1962 - Col ferro e col fuoco (dir. Fernando Cerchio) - portrayed by Akim Tamiroff

- 1969 - Pan Wołodyjowski (dir. J. Hoffman) - portrayed by Mieczysław Pawlikowski

- 1969 - Przygody pana Michała (TV series) (dir. P. Komorowski) - portrayed by Mieczysław Pawlikowski

- 1974 - Potop (dir. J. Hoffman) - portrayed by Kazimierz Wichniarz

- 1999 - Ogniem i mieczem (dir. J. Hoffman) - portrayed by Krzysztof Kowalewski

References

- Stanisław Kozłowski (1892). "Henryk Sienkiewicz jako powieściopisarz historyczny". Biblioteka warszawska. A. Krasiński. pp. 530–535. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Stanisława Grabska (2002). "Between Recklessness and Hope". In Leon Dyczewski (ed.). Values in the Polish Cultural Tradition. CRVP. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-56518-142-7. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- George Weigel (18 September 2003). The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-19-516664-4. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- "ZAGŁOBA JAN ONUFRY herbu Wczele (lit.)". Encyklopedia.interia.pl. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- Roman Dyboski (1971). "Literature, Art and Learning in Poland since 1863". In William Fiddian Reddaway (ed.). The Cambridge History of Poland. CUP Archive. pp. 538–. GGKEY:2G7C1LPZ3RN. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Horst Frenz (1 December 1999). Literature: 1901-1967. World Scientific. p. 39. ISBN 978-981-02-3413-3. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Nevin Otto Winter (1923). The New Poland: The Story of the Resurrection of a Submerged People. Ayer Publishing. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-0-8369-6757-9. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- William Lyon Phelps (30 June 2006). Essays On Modern Novelists. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-4286-3038-3. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Edward Bolland Osborn (1922). Literature and Life: Things Seen, Heard, and Read. Ayer Publishing. p. 45. GGKEY:DY8LJW7A3EW. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Tomasz Pohl. Motywy kulturowe i historyczne w przekazach reklamowych. Tomasz Pohl. p. 10. ISBN 978-83-929374-0-1. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jan Zagłoba. |

- Andrzej Stoff (2006). "Zagłoba sum!": studium postaci literackiej. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika. ISBN 978-83-231-1996-8. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Aleksander Rowiński. Pan Zagłoba. Agencja Wydawnicza Ostroróg. ISBN 978-83-86281-18-3. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Zagłoba (1941). Od zagłoby do Wiecha: humor w literaturze polskiej. A. Wilmot. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Henryk Sienkiewicz (1890). With Fire and Sword: An Historical Novel of Poland and Russia. Little, Brown. Retrieved 21 September 2012. (free public domain text)