Umbri

The Umbri were Italic people of ancient Italy.[1] A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were settled in the 9th-4th centuries BC on easily defensible hilltops. Umbria was bordered by the Tiber and Nar rivers and included the Apennine slopes on the Adriatic. The ancient Umbrian language is a branch of a group called Oscan-Umbrian, which is related to the Latino-Faliscan languages.[2]

Etymology

They are also called Ombrii in some Roman sources. Some Roman writers thought the Umbri to be of Celtic origin; Cornelius Bocchus wrote that they descended from an ancient Gaulish tribe. Plutarch wrote that the name might be a different way of writing the name of the Celto-Germanic tribe Ambrones, which loosely means "King of the Boii." He also suggested that the Insubres, another Gaulish tribe, might be connected; their Celtic name Isombres could possibly mean "Lower Umbrians," or inhabitants of the country below Umbria.[3] Similarly Roman historian Cato the Elder, in his masterpiece Origines, defines the Gauls "the progenitors of the Umbri".[4]

The Ambrones are mentioned, with the Lombards and the Suebi, among the Germanic tribes of Northern Europe in the poem Widsith.[5] Furthermore, according to Roman authors, the Ambrones originated somewhere in Germany or Scandinavia.[6][7] Pliny the Elder wrote concerning the folk-etymology of the name:

The Umbrian people are thought the oldest in Italy; they are believed to have been called Ombrii (here, "the people of the thunderstorm," after ὅμβρος, "thunderstorm") by the Greeks because they survived the deluge (literally "the inundation of the lands by thunderstorms, imbribus). The Etruscans vanquished 300 Umbrian cities.[8]

Religion

During the 6th–4th centuries BC, Umbrian communities constructed rural sanctuaries in which they sacrificed to the gods. Bronze votives shaped as animals or deities were also offered. Umbrian deities include Feronia, Valentia, Minerva Matusia and Clitumnus. The Iguvine Tablets were discovered in 1444 at Gubbio, Italy. Composed during the 2nd or 3rd centuries BC, they describe religious rituals involving animal sacrifice.[9]

Political structure

Two men held the supreme magistracy of uhtur and were responsible for supervising rituals. Other civic offices included the marone, which had a lower status than uhtur, and a religious position named kvestur. The Umbrian social structure was divided into distinct groups probably based upon military rank. During the reign of Augustus, four Umbrian aristocrats became senators. Emperor Nerva’s family was from Umbria.[10]

According to Guy Jolyon Bradley, " The religious sites of the region have been thought to reveal a society dominated by agricultural and pastoral concerns, to which town life came late in comparison to Etruria."[11]

Roman influence

Throughout the 9th-4th centuries BC, imported goods from Greece and Etruria were common, as well as the production of local pottery.

The Romans first made contact with Umbria in 310 BC and settled Latin colonies there in 299 BC, 268 BC and 241 BC. They had completed their conquest of Umbria by approximately 260 BC. Incorporation into the Roman state occurred during the 3rd century BC when some Umbri were given full citizenship or citizenship without the right to vote. Also during the 3rd century BC about 40,000 Romans settled in the region. The Via Flaminia linking areas of Umbria was complete by 220 BC. Cities in Umbria also contributed troops to Rome for its many wars. Umbrians fought under Scipio Africanus in 205 BC during the Second Punic War. The Praetorian Guard recruited from Etruria and Umbria. The Umbri played a minor role in the Social War and as a result were granted citizenship in 90 BC. Roman veterans were settled in Umbria during the reign of Augustus.[12]

Archaeological sites

The Umbrians descend from the culture of Terni, protohistoric facies of southern Umbria. The towns of Chianciano and Clusium (Umbrian: Camars) near modern Arezzo contain traces of Umbrian habitation dating to the 7th or 8th centuries BC. Terni (in Latin: Interamna Nahars) was the first important Umbrian center. Its population was called with the name of Umbri Naharti. They were the largest, organized and belligerent tribe of the Umbrians and populated compactly across the basin of Nera River. This people are quoted for 7 times in the Iguvine Tablets. This is confirmed not only by the Iguvine Tablets, Latin historians and by the important and privileged role played by this city in Roman times, but also by the discovery, at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, of one of the mixed burial necropolis (Urnfield culture and burial fields) larger of Europe, about 3000 tombs (Necropoli delle Acciaierie di Terni).

Assisi, called Asisium by the Romans, was an ancient Umbrian site on a spur of Mount Subasio. Myth relates that the city was founded by Dardanus in 847 BC.

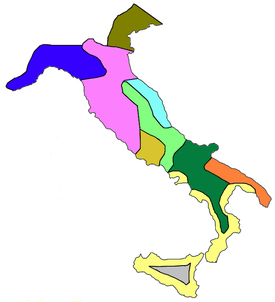

Perugia and Orvieto are not considered of Umbrian but Etruscan origin. According to the geographical distribution of the Umbrian territory, they are located on the left side of the Tiber River, which is part of the ancient Etruria. Umbri were on the opposite side of the river. According to the map of Regio Umbria and Ager Galliucus by Emperor Augustus , the major Umbrian city-state were: Terni, Todi, Amelia and Spoleto (the current part of southern Umbria). While north Umbrian cities such as Gubbio or Città di Castello will be affected by the influence of Etruscan culture (a try are the Iguvine Tablets), they will develop a form of writing that is mix of Umbrian and Etruscan language, while the southern Umbrians (the purest and conservative in terms of tradition, language and culture) will not have.

Prominent Umbri

Gentes of Umbrian origin

Romans of Umbrian ancestry

- Nerva, Roman emperor

- Trajan, Roman emperor

- Seneca the Elder, rhetorician and writer

- Seneca the Younger, Stoic philosopher, statesman and dramatist,

See also

References

- Pliny, Natural History Vol 3, chap. 19.

- Buck, Carl Darling (1904). A grammar of Oscan and Umbrian : with a collection of inscriptions and a glossary. Robarts - University of Toronto. Boston : Ginn.

- Prichard, Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind: In Two Volumes, Volume 2, p. 60

- Troya, Charles (1839). Storia d'Italia del medio-evo e codice diplomatico Longobardo. p. 253.

- Widsith, lines 31-33

- "Ambrones". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Plutarch, The Lives, The Life of Marius.

- Pliny the Elder, Book III, chap. 19, paragraphs 112-113. Also at wikisource latina

- Poultney, 1959

- Bradley, 2000

- Ancient Umbria: State, Culture, and Identity in Central Italy from the Iron Age to the Augustan Era.

- Bradley, 2000

Sources

- Bradley, Guy (2000). Ancient Umbria. State, culture, and identity in central Italy from the Iron Age to the Augustan era. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Domenico, Roy P. (2001). Regions of Italy: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. pp. 367–371.

- Pliny (1961). Natural History with an English translation in ten volumes by H. Rackham. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Poultney, James Wilson (1959). The Bronze Tables of Iguvium. American Philological Association, Number XVIII.