Okemah, Oklahoma

Okemah (/ˌoʊˈkimə/ or /ˈʌkimə/)[5] is the largest city in and the county seat of Okfuskee County, Oklahoma, United States.[6] It is the birthplace of folk music legend Woody Guthrie. Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, a federally recognized Muscogee Indian tribe, is headquartered in Okemah. The population was 3,223 at the 2010 census, a 6.1 percent increase from 3,038 in 2000. In that census, about 26.6 percent of the residents identified themselves as Native American.[7]

Okemah, Oklahoma | |

|---|---|

City | |

West Broadway, Downtown | |

| Motto(s): " Home Of Woody Guthrie And The Woody Guthrie Folk Festival " | |

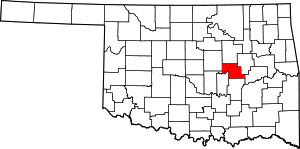

Location of Okemah, Oklahoma | |

| Coordinates: 35°25′52″N 96°18′20″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oklahoma |

| County | Okfuskee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.62 sq mi (6.78 km2) |

| • Land | 2.53 sq mi (6.55 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.24 km2) |

| Elevation | 909 ft (277 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,223 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 3,132 |

| • Density | 1,238.92/sq mi (478.38/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 74859 |

| Area code(s) | 539/918 |

| FIPS code | 40-54200[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1096198[4] |

| Website | okemahok.org |

History

Historically occupied by the Osage and Quapaw, who ceded their lands to the United States by 1825, the area was assigned to the Creek Nation and specifically the Thlopthlocco Tribal Town after Indian Removal of tribes from the Southeast United States in the 1830s.

Okemah was named after a Kickapoo Indian chief. In March 1902, Chief Okemah built a bark house in his tribe's traditional fashion. He had come to await the opening of the townsite, which took his name on April 22, 1902. In the Kickapoo language, okemah means "things up high," such as highly placed person or town or high ground.

In preparation for Oklahoma's statehood, the Dawes Commission was authorized in 1896 to work with the Five Civilized Tribes to enroll their members for allotments of tribal land to individual households. Registration of tribal members lasted from 1898 to 1906. After allotment, the government was going to declare the remaining tribal lands "surplus" and sell them to European-American settlers.

Okemah was platted by a group of Shawnee residents in March 1902 on land belonging to Mahala and Nocus Fixico, full-blood Creek. The Fixicos had no legal right at the time to sell their holding, as enrollment of tribal members on the Dawes Roll continued until 1906, and no land sales were to take place by Indians until it was completed. That did not appear to affect the promoters or the development of the town.

On April 22, 1902, the formal opening launched the town. A post office opened on May 16,[8] and the town was incorporated in 1903. In the spring of 1904, Commission restrictions on the sale of townsite lots were removed. The Department of the Interior trustees of land held by American Indians paid the Fixicos $50 an acre for their land, and gave legal deeds to the purchasers who claimed title.

In the town's first week, the following stores were established: four general merchandise, two hardware, one 5 & 10 cent store, three drugstores, four groceries, three wagon yards, four lumberyards, three cafes, one bakery, two millineries, four livery barns, three blacksmiths, two dairies, two cotton gins and two weekly newspapers. Eight doctors settled there, four lawyers, two walnut log buyers, and one Chinese laundryman. Two hotels were quickly put up, including the three-story Broadway hotel, which set the city apart as an important town in early Oklahoma.

Okfuskee County had been organized at the time of statehood in 1907. Okemah was chosen as county seat in a county election held August 27, 1908.

Firsts

The townsite was selected by two railroad surveyors, Perry Rodkey and H.R. Dexter. Dexter is credited with choosing the town name. They picked the site believing that two railroads, the Fort Smith and Western Railroad and the Ozark and Cherokee Central Railway (later the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway) would intersect there. While the former did build a line through the site, the latter never did.[8]

The town's first state-chartered bank began business the day of the opening, April 22, 1902, in a tent on the northwest corner of the present Fifth and Broadway (now City Hall). C. J. Benson was president. W. H. Dill was vice president and served as cashier. It became the First National Bank[9] in 1903, but was liquidated in 1939, having failed due to the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression.

J. E. Galloway was the first mayor; Perry Rodkey, first postman; E. D. Dexter, first hotel operator; Dill ran the first telephone company; John D. Richards had the first hardware store; McGee Brothers put in the first cotton gin; and E. E. Shook established the first lumberyard. The first church in the city was the North Methodist, at Sixth and Ash, but the first church service Baptist, presided over by the Rev. Black. The editor Charles Barnclaw published the first newspaper.

Lynching

Although a police force was organized in the town soon after its founding (a Mr. Franklin wore the first city policeman's badge), vigilantes were active during Okemah's early years. Law enforcement and justices of the peace were located some distance away. The vigilantes appeared to have had almost complete freedom of action.

In 1911, a black woman, 35-year-old Laura Nelson, and her teenage son, L. D., were lynched by a mob of white men. Accused of killing a police officer in an altercation at their home near Paden, they were kidnapped from the Okemah county jail and hanged from a suspension bridge over the North Canadian River.[10]

Geography

Okemah is located at 35°25′52″N 96°18′20″W (35.430987, -96.305500).[11] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.7 square miles (7.0 km2), of which 2.6 square miles (6.7 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (2.63%) is water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 1,389 | — | |

| 1920 | 2,162 | 55.7% | |

| 1930 | 4,002 | 85.1% | |

| 1940 | 3,811 | −4.8% | |

| 1950 | 3,454 | −9.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,836 | −17.9% | |

| 1970 | 2,913 | 2.7% | |

| 1980 | 3,381 | 16.1% | |

| 1990 | 3,085 | −8.8% | |

| 2000 | 3,038 | −1.5% | |

| 2010 | 3,223 | 6.1% | |

| Est. 2019 | 3,132 | [2] | −2.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 3,038 people, 1,242 households, and 763 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,170.5 people per square mile (451.1/km2). There were 1,506 housing units at an average density of 580.3 per square mile (223.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 69.09% White, 2.37% African American, 22.84% Native American, 0.10% Asian, 0.46% from other races, and 5.13% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.94% of the population.

There were 1,242 households out of which 29.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.8% were married couples living together, 15.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.5% were non-families. 35.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 18.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 3.04.

In the city, the population was spread out with 27.4% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 23.3% from 25 to 44, 19.9% from 45 to 64, and 20.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $21,306, and the median income for a family was $26,659. Males had a median income of $21,905 versus $15,375 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,645. About 19.5% of families and 25.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 38.6% of those under age 18 and 16.6% of those age 65 or over.

Education

History

S. L. O'Bannon was the teacher in the first school, which opened in 1902 with funds gained by subscribers. Classes were held in a store building. The first school building was built in 1902. It was later replaced by the Wilson School on the same site. The first public school was opened with Dr. Z. Cheatwood as superintendent in 1904.

A store building housed one of the first public schools, and the other was held in a building where the American Legion building now stands. Noble School, completed in 1907, was named for Miss Mae Noble. Okemah High School gained accreditation in 1912. It met in the old Noble School building until the building of 1918 was erected. In the high school complex, the band shop building was erected 1941 and a vocational building in 1948.

Parks, recreation and events

Okemah Lake, north of town, is a city lake that features swimming, boating, hunting, fishing, and camping.[13]

Okemah’s Municipal Park at Ash St. and S. 2nd St., now with picnic tables and playground equipment, was originally constructed by the WPA in 1935.[14]

Pioneer Days in Okemah are the last weekend in April annually.[15]

The Woody Guthrie Folk Festival, also known as WoodyFest, occurs annually in July.[16]

Transportation

Okemah is at the intersection of Interstate 40 and State Highway 56.[17]

Okemah Airport (FAA Identifier: F81), two miles south of town, features a 3,400-foot runway.[18]

Notable people

- Larry Coker - Football coach

- Evan Felker - Lead singer for country music band Turnpike Troubadours

- John Fullbright - americana singer/songwriter

- Woody Guthrie - Folk singer

- Robert Higgs - Economic historian

- Leon C. Phillips - Governor of Oklahoma, 1939–43

- William Reid Pogue - astronaut

- Shawna Russell - country singer/songwriter

NRHP sites

The following sites in Okemah are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

- Okemah Armory

- Okfuskee County Courthouse

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Rick Aschmann (2 May 2018). "North American English Dialects, Based on Pronunciation Patterns". Aschmann.net. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- CensusViewer:Okemah, Oklahoma Population

- Price, Carolyn S. Burnett. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Okemah." Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- The Bankers Magazine - Volume 76 - Page 647 - Google Books Result 1908 - Banks and banking Okemah—First National Bank: R. W. Armstrong, Asst. Cashicr.

- Davidson, James West (2007). "They say": Ida B. Wells and the Reconstruction of Race. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 5–8.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Okemah Lake". City of Okemah. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- "Municipal Park-Okemah OK". The Living New Deal. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- "Pioneer Days". City of Okemah. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- "History of the Festival". Woody Guthrie Folk Festival. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- "Okemah, Oklahoma". Google Maps. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- "Airport". City of Okemah. Retrieved July 3, 2020.