Oestrus ovis

Oestrus ovis, the sheep bot fly, is a widespread species of fly of the genus Oestrus. It is known for its parasitic predation and damage to sheep, deer, goats and sometimes cattle. There have also been many records of horse, dog[1] and human infestation. In some areas of the world it is a significant pest which affects the agricultural economy.[2]

| Oestrus ovis | |

|---|---|

._C_Wellcome_V0022564.jpg) | |

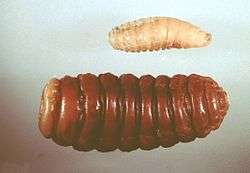

| The larva and fly of the sheep-nostril-fly (Oestrus ovis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Oestrus |

| Species: | O. ovis |

| Binomial name | |

| Oestrus ovis | |

Description

The adult fly is a bee-like insect about 10 to 12 millimetres (3/8–½ inches) long, slightly hairy with a banded, dark grey body and dull yellow head and legs.[3] It is widely distributed across the world wherever sheep, deer and goats are found. This includes North America, Central America, the area round the Mediterranean Sea, The Middle East, Australia, Brazil and South Africa. Incidence of the fly in northern Europe has decreased in recent years.[4]

Life cycle

Sheep bot flies commence life as eggs within the female which are fertilised and hatch to larvae of 1 mm within the body of the female. The female then deposits a few larvae, while on the wing, within a tiny mucous drop, directly into a nostril of the host animal. The larvae then make their way up the nasal passage in the mucosa and enter a nasal sinus. During this time it will develop, grow and moult into a second larval stage or instar. It then continues to develop up to 20mm (approximately 4/5 inch) in length with a dark stripe across each segment. When the larva is fully developed it moves down the nasal passage and drops to the ground where it buries itself and pupates. The length of time the larva takes to mature depends on the ambient temperature. This may be 25–35 days in warm weather but up to 10 months in colder climates. The pupa takes from 3–9 weeks to mature, again dependent on climatic conditions, after which the adult burrows up to the surface, takes to the wing and commences mating. The adults do not feed during their 2–4 weeks of adult life though they may take water.[3]

Effects on livestock

Sheep are the principal hosts. The presence of the fly with its distinctive buzzing can alert mature animals who may attempt to run away, walk with their noses near the ground[3] or have been recorded forming a circle with their noses in the middle and near the ground.[3][4] If the fly successfully places eggs in the nostril of sheep the animal may feel the larvae after a few days and attempt to remove them by tapping their muzzles on the ground. They will also snort and stamp their front feet in annoyance.[3] Once the larvae have infested the nasal passage and sinuses, usually up to 15 larvae but can be up to 80, they cause irritation to the mucosa, which causes mucous discharge, swelling of the internal membranes of the nose, possibly impairment of breathing but largely discomfort and distraction to the sheep who may reduce or stop grazing and subsequently lose weight and condition.[4] This can in some cases lead to malnutrition and death [3] Sometimes mature larvae are unable to escape from the nasal sinus and die. This may then lead to a septic sinusitis affecting the animal's condition.[4] and the possibility of death from general septicaemia.[3]

Control of infestation

In developed countries sheep and other domestic animals can be given preventative medication in the form of drenches. These have a variable effect because reinfestation from neighbouring territory is common. In isolated flocks of animals control can be more effective.[4]

Human infestation

There have been widespread reports of human infestation going back over decades, and probably centuries.[5] Most commonly they are shepherds living in close proximity to the sheep[6] but there are records of hapless visitors being subject to infestation and carrying the parasites home to their native country.[7] The effects can usually be treated easily with medical attention or medication.

See also

References

- McGarry, J.; Penrose, F; Collins, C (2012), "Oestrus ovis infestation of a dog in the UK.", Journal of Small Animal Practice, 53 (3): 192–93, doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01158.x, PMID 22122385

- Lloyd, John E; Brewer, Michael J (Apr 1992), Sheep Bot Fly Biology and Management (PDF), Dept. of Plant, Soil and Insect Sciences, Wyoming Univ., retrieved 2012-04-01

- Capelle, Kenneth J. (1966), "The Occurrence of Oestrus ovis L. in the Bighorn Sheep from Wyoming and Montana. Vol.52, No.3", The Journal of Parasitology, 52 (3): 618–621, JSTOR 3276337

- Sheep Nose Bot, New Jersey, USA: Merk Sharp and Dohme Corp., 2011, retrieved 2012-04-01

- Pampiglione, S.; Gianetto, S.; Virga, A. (Dec 1997), "Persistence of human myiasis by oestrus ovis L. among shepherds of the Etnean area (Sicily) for over 150 years.", Parassitologia, 39 (4): 415–418, PMID 9802104

- Masoodi, Mohsen; Hosseini, Keramatalah (2004), External Ophthalmomyiasis Caused by Sheep Botfly (oestrus ovis) Larva: A Report of 8 Cases. (PDF), Archives of Iranian Medicine Vol.7 No.2, pp. 136–139, retrieved 2012-04-01CS1 maint: location (link)

- Gregory, A.R.; Schatz, S.; Lambaugh, H. (2004), "Ophthalmomyiasis caused by the sheep bot fly, oestrus ovis, in northern Iraq.", Optom Vis Sci, 81 (8): 586–90, doi:10.1097/01.opx.0000141793.10845.64, PMID 15300116