Ode to Joy

"Ode to Joy" (German: "An die Freude" [an diː ˈfʁɔʏdə]) is an ode written in the summer of 1785 by German poet, playwright, and historian Friedrich Schiller and published the following year in Thalia. A slightly revised version appeared in 1808, changing two lines of the first and omitting the last stanza.

| by Friedrich Schiller | |

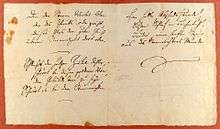

Autograph manuscript, circa 1785 | |

| Original title | An die Freude |

|---|---|

| Written | 1785 |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Form | Ode |

| Publisher | Thalia |

| Publication date | 1786, 1808 |

"Ode to Joy" is best known for its use by Ludwig van Beethoven in the final (fourth) movement of his Ninth Symphony, completed in 1824. Beethoven's text is not based entirely on Schiller's poem, and introduces a few new sections. His tune[1] (but not Schiller's words) was adopted as the "Anthem of Europe" by the Council of Europe in 1972 and subsequently by the European Union. Rhodesia's national anthem from 1974 until 1979, "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia", used the tune of "Ode to Joy".

The poem

Schiller wrote the first version of the poem when he was staying in Gohlis, Leipzig. In the year 1785 from the beginning of May till mid September, he stayed with his publisher Georg Joachim Göschen in Leipzig and wrote "An die Freude" along with his play Don Carlos.[2]

Schiller later made some revisions to the poem which was then republished posthumously in 1808, and it was this latter version that forms the basis for Beethoven's setting. Despite the lasting popularity of the ode, Schiller himself regarded it as a failure later in his life, going so far as to call it "detached from reality" and "of value maybe for us two, but not for the world, nor for the art of poetry" in an 1800 letter to his long-time friend and patron Christian Gottfried Körner (whose friendship had originally inspired him to write the ode).[3]

Lyrics

| "An die Freude" | "Ode to Joy" |

|---|---|

Freude, schöner Götterfunken, |

Joy, beautiful spark of Divinity [or: of gods], |

Revisions

The lines marked with * have been revised as follows:

| Original | Revised | Translation of original | Translation of revision | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| was der Mode Schwerd geteilt | Was die Mode streng geteilt | what the sword of custom divided | What custom strictly divided | The original meaning of Mode was "custom, contemporary taste".[4] |

| Bettler werden Fürstenbrüder | Alle Menschen werden Brüder | beggars become brothers of princes | All people become brothers | |

Ode to freedom

Academic speculation remains as to whether Schiller originally wrote an "Ode to Freedom" (Ode an die Freiheit) and changed it to an "Ode to Joy".[5][6] Thayer wrote in his biography of Beethoven, "the thought lies near that it was the early form of the poem, when it was still an 'Ode to Freedom' (not 'to Joy'), which first aroused enthusiastic admiration for it in Beethoven's mind".[7] The musicologist Alexander Rehding points out that even Bernstein, who used "Freiheit" in one performance in 1989, called it conjecture whether Schiller used "joy" as code for "freedom" and that scholarly consensus holds that there is no factual basis for this myth.[8]

Use of Beethoven's setting

Over the years, Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" has remained a protest anthem and a celebration of music. Demonstrators in Chile sang the piece during demonstration against the Pinochet dictatorship, and Chinese students broadcast it at Tiananmen Square. It was performed (conducted by Leonard Bernstein) on Christmas day after the fall of the Berlin Wall replacing "Freude" (joy) with "Freiheit" (freedom), and at Daiku (Number Nine) concerts in Japan every December and after the 2011 tsunami.[9] It has recently inspired impromptu performances at public spaces by musicians in many countries worldwide, including Choir Without Borders's 2009 performance at a railway station[10] in Leipzig, to mark the 20th and 25th anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall, Hong Kong Festival Orchestra's 2013 performance at a Hong Kong mall, and performance in Sabadell, Spain.[11] A 2013 documentary, Following the Ninth, directed by Kerry Candaele, follows its continuing popularity.[9][12] It was played after Emmanuel Macron's victory in the 2017 French Presidential elections, when Macron gave his victory speech at the Louvre.[13] Pianist Igor Levit played the piece at the Royal Albert Hall during the 2017 Proms.[14] The BBC Proms Youth Choir performed the piece alongside Georg Solti's UNESCO World Orchestra for Peace at the Royal Albert Hall during the 2018 Proms at Prom 9, titled "War & Peace" as a commemoration to the centenary of the end of World War One.[15]

The song's Christian context was one of the main reasons for Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism to excommunicate the Soka Gakkai organization for their use of the hymn at their meetings.[16]

Other musical settings

Other musical settings of the poem include:

- Christian Gottfried Körner (1786)

- Carl Friedrich Zelter (1792), for choir and accompaniment, later rewritten for different instrumentations.

- Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1796)

- Ludwig-Wilhelm Tepper de Ferguson (1796)

- Johann Friedrich Hugo von Dalberg (1799)

- Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg (1803)

- Franz Schubert's song "An die Freude", D 189, for voice, unison choir and piano. Composed in May 1815, Schubert's setting was first published in 1829 as Op. post. 111 No. 1. The 19th century Gesamt-Ausgabe included it as a lied in Series XX, Volume 2 (No. 66). The New Schubert Edition groups it with the part songs in Series III (Volume 3).[17]

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1865), for solo singers, choir and orchestra in a Russian translation

- Pietro Mascagni cantata "Alla gioia" (1882), Italian text by Andrea Maffei

- "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" (1892), waltz by Johann Strauss II

- Z. Randall Stroope (2002), for choir and four-hand piano

- Victoria Poleva (2009), for soprano, mixed choir and symphony orchestra

References

- The usual name of the Hymn tune is "Hymn to Joy" "Hymnary – Hymn to Joy". Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "History of the Schiller House". stadtgeschichtliches-museum-leipzig.de.

- Schiller, Friedrich (October 21, 1800). "[Untitled letter]". wissen-im-netz.info (in German). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- Duden – Das Herkunftswörterbuch. Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut. 1963. p. 446. ISBN 3-411-00907-1. The word was derived via French from ultimately Latin modus. Duden cites as first meanings "Brauch, Sitte, Tages-, Zeitgeschmack". The primary modern meaning has shifted more towards "fashion".

- Kubacki, Wacław (January 1960). "Das Werk Juliusz Slowackis und seine Bedeutung für die polnische Literatur". Zeitschrift für Slawistik (in German). 5 (1). doi:10.1524/slaw.1960.5.1.545.

- Görlach, Alexander (4 August 2010). "Der Glaube an die Freiheit – Wen darf ich töten?". The European.

Das 'Alle Menschen werden Brüder', das Schiller in seiner Ode an die Freude (eigentlich Ode an die Freiheit) formuliert, ...

- Thayer, A. W.(1817–97), rev. and ed. Elliot Forbes. Thayer's Life of Beethoven. (2 vols. 1967, 1991) Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 895.

- Rehding, Alexander (2018). Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. Oxford University Press. p. 33, note 8 on p. 141. ISBN 9780190299705.

- Daniel M. Gold (October 31, 2013). "The Ode Heard Round the World: Following the Ninth Explores Beethoven's Legacy". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 Sep 2014.

- Video of a "flash mob" – "Ode to Joy" sung at Leipzig railway station (8 November 2009) on YouTube

- Megan Garber (9 July 2012). "Ode to Joy: 50 String Instruments That Will Melt Your Heart". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "Beethoven's Flash Mobs". billmoyers.com. November 14, 2013.

- Nougayrède, Natalie (8 May 2017). "Macron's victory march to Europe's anthem said more than words". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "EU anthem played at Proms' first night". BBC News. BBC. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Prom 9: War & Peace". BBC Music Events. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- Excommunication, daisakuikeda.org (undated)

- Otto Erich Deutsch et al. Schubert Thematic Catalogue, German edition 1978 (Bärenreiter), pp. 128–129

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ode an die Freude. |

- An die Freude text and translations at The LiederNet Archive

- German and English text, Schiller Institute