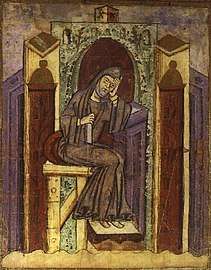

Notker the Stammerer

Notker the Stammerer (Latin: Notcerus Balbulus;[1] c. 840 – 6 April 912 AD), also called Notker I, Notker the Poet or Notker of Saint Gall, was a musician, author, poet, and Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Saint Gall, now in Switzerland. He is commonly accepted to be the "Monk of Saint Gall" (Monachus Sangallensis) who wrote Gesta Karoli (the "deeds of Charlemagne").[2]

Blessed Notker of Saint Gall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Monk | |

| Born | c. 840 Heligau or Jonschwil |

| Died | 912 Abbey of Saint Gall |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Western Orthodox Church |

| Beatified | 1512 |

| Feast | 7 April |

| Attributes | A rod; Benedictine habit; book in one hand and a broken rod in the other with which he strikes the Devil |

| Patronage | Musicians; invoked against stammering |

Biography

Notker was born around 840, to a distinguished family. He would seem to have been born at Jonschwil on the River Thur, south of Wil, in what would become much later (in 1803) the canton of Saint Gall in Switzerland; some sources claim Elgg to be his place of birth. He studied with Tuotilo at Saint Gall's monastic school, and was taught by Iso of St. Gallen, and the Irishman, Moengall. He became a monk there and is mentioned as librarian in 890 and as master of guests in 892–4. He was chiefly active as a teacher, and displayed refinement of taste as poet and author.[3]

Ekkehard IV, the biographer of the monks of Saint Gall, lauds him as "delicate of body but not of mind, stuttering of tongue but not of intellect, pushing boldly forward in things Divine, a vessel of the Holy Spirit without equal in his time".[3] He died in 912. He was beatified in 1512.

Works

He completed Erchanbert's chronicle, arranged a martyrology, composed a metrical biography of Saint Gall, and authored other works.[3]

In his martyrology, he appeared to corroborate one of St Columba's miracles. St Columba, being an important father of Irish monasticism, was also important to St Gall and thus to Notker's own monastery. Adomnan of Iona had written that at one point Columba had through clairvoyance seen a city in Italy near Rome being destroyed by fiery sulphur as a divine punishment and that three thousand people had perished. And shortly after Columba saw this, sailors from Gaul arrived to tell the news of it. Notker claimed in his martyrology that this event happened and that an earthquake had destroyed a city which was called 'new'. It is unclear what this city was that Notker was claiming, although some thought it may have been Naples (previously called 'Neapolis' – new city). However Naples was destroyed by a volcano in 512 before Columba was born, and not during Columba's lifetime.[4]

His Liber Hymnorum, created between 881 and 887, is an early collection of Sequences, which he called "hymns", mnemonic poems for remembering the series of pitches sung during a melisma in plainchant, especially in the Alleluia. It is unknown how many or which of the works contained in the collection are his. The hymn Media Vita, was erroneously attributed to him late in the Middle Ages.

Ekkehard IV wrote of fifty sequences composed by Notker. He was formerly considered to have been the inventor of the sequence, a new species of religious lyric, but this is now considered doubtful, though he did introduce the genre into Germany. It had been the custom to prolong the Alleluia in the Mass before the Gospel, modulating through a skillfully harmonized series of tones. Notker learned how to fit the separate syllables of a Latin text to the tones of this jubilation; this poem was called the sequence (q.v.), formerly called the "jubilation". (The reason for this name is uncertain.) From 881–7 Notker dedicated a collection of such verses to Bishop Liutward of Vercelli, but it is not known which or how many are his.

The Monk of Saint Gall

The "Monk of Saint Gall" (Latin: Monachus Sangallensis; the name is not contemporary, being given by modern scholars), the ninth-century writer of a volume of didactic eulogistic anecdotes regarding the Emperor Charlemagne, is now commonly believed to be Notker the Stammerer.[5] This monk is known from his work to have been a native German-speaker, deriving from the Thurgau, only a few miles from the Abbey of Saint Gall; the region is also close to where Notker is believed to have derived from. The monk himself relates that he was raised by Adalbert, a former soldier who had fought against the Saxons, the Avars ("Huns" in his text) and the Slavs under the command of Kerold, brother of Hildegard, Charlemagne's second wife; he was also a friend of Adalbert's son, Werinbert, another monk at Saint Gall, who died as the book was in progress.[6] His teacher was Grimald von Weißenburg, the Abbot of Saint Gall from 841 to 872, who was, the monk claims, himself a pupil of Alcuin.

The monk's untitled work, referred to by modern scholars as De Carolo Magno ("Concerning Charles the Great") or Gesta Caroli Magni ("The Deeds of Charles the Great"), is not a biography but consists instead of two books of anecdotes relating chiefly to the Emperor Charlemagne and his family, whose virtues are insistently invoked. It was written for Charles the Fat,[7] great-grandson of Charlemagne, who visited Saint Gall in 883.[8] It has been scorned by traditional historians, who refer to the Monk as one who "took pleasure in amusing anecdotes and witty tales, but who was ill-informed about the true march of historical events", and describe the work itself as a "mass of legend, saga, invention and reckless blundering": historical figures are claimed as living when in fact dead; claims are attributed to false sources (in one instance,[9] the Monk claims that "to this King Pepin [the Short] the learned Bede has devoted almost an entire book of his Ecclesiastical History"; no such account exists in Bede's history – unsurprisingly, given that Bede died in 735 during the reign of Charlemagne's grandfather Charles Martel); and Saint Gall is frequently referenced as a location in anecdotes,[10] regardless of historical verisimilitude (Pepin the Hunchback, for example, is supposed to have been sent to Saint Gall as punishment for his rebellion, and – in a trope owed to Livy's tale of Tarquin and the poppies – earns a promotion to rich Prüm Abbey after advising Charlemagne through an implicit parable of hoeing thistles to execute another group of rebels). The Monk also mocks and criticizes bishops and the prideful, high-born incompetent, showy in dress and fastidious and lazy in habits, whilst lauding the wise and skillful government of the Emperor with nods to the deserving poor. Several of the Monk's tales, such as that of the nine rings of the Avar stronghold, have been used in modern biographies of Charlemagne.

The Monk of Saint Gall is commonly believed to be Notker the Stammerer: Louis Halphen[11] has delineated the points of similarity between the two: the Monk claims to be old, toothless and stammerering; and both share similar interests in church music, write with similar idioms, and are fond of quoting Virgil.[12] The text is dated to the 880s from mentions in it of Carloman (died 880), half-brother of Charles the Fat, the "circumscribed lands" of Carloman's son Arnulf, who succeeded as King of the Germans in 887, and the destruction of Prüm Abbey, which occurred in 882.

References

- "Cantica Chorus Gregorianus - Annotamentum". www.cantica.be. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Derek Wilson, Charlemagne: A Biography, p. 146.

- Kampers, Franz, and Klemens Löffler. "Notker." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 11 February 2016

- Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Penguin books, 1995

- "The Monk of Saint Gall", Medieval Sourcebook, Fordham University

- i, Postscript.

- Innes, M. (1998) "Memory, orality and literacy in an early medieval society", Past and Present, 158, pp. 3–36.

- The visit is mentioned, i.34.

- ii.16.

- i.12, etc.

- Halphen, "Le moine de Saint-Gall", in his Études critiques sur l'histoire de Charlemagne, 1921, ch. 4:139-42.

- Ekkehard of St. Gall. "Three Monks of St. Gall". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

Further reading

- Hoppin, Richard. Medieval Music. New York: Norton, 1978. Pages 155–156.

- Thorpe, Lewis, Two Lives of Charlemagne

- Yudkin, Jeremy. Music in Medieval Europe. Page 221

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Notker the Stammerer |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Notker the Stammerer. |

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Latina with analytical indexes

- Catholic Encyclopedia, accessed on 25 April 2006

- Saint of the Day, April 6: Notker Balbulus at SaintPatrickDC.org

- Works by Notker the Stammerer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Notker the Stammerer at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)