Niqmi-Epuh

Niqmi-Epuh, also given as Niqmepa (reigned c. 1700 BC – c. 1675 BC - Middle chronology ) was the king of Yamhad (Halab) succeeding his father Yarim-Lim II

| Niqmi-Epuh | |

|---|---|

| Great King of Yamhad | |

| |

| Reign | c. 1700 BC – c. 1675 BC. Middle chronology |

| Predecessor | Yarim-Lim II |

| Successor | Irkabtum |

Reign

Little of Aleppo has been excavated by archaeologists, knowledge about Niqmi-Epuh comes from tablets discovered at Alalakh.[1] His existence is confirmed by a number of tablets with his seal on their envelope[2]

Yarim-Lim king of Alalakh, uncle of Yarim-Lim II and vassal of Yamhad died during Niqmi-Epuh's reign and was succeeded by his son Ammitakum,[3] who started to assert Alalakh's semi-independence.[4]

The tablets mention Niqmi-Epuh's votive status which he dedicated to Hadad and placed it in that deity's Temple.[5] Tablet AlT*11 informs of his return from Nishin, a place not known before, but certainly inside the territory of Yamhad because the tablet seems to refer to travel and not a military campaign.[6]

Niqmi-Epuh's most celebrated deed was his conquest of the town Arazik, near Charchemish,[7] the fall of this city was important to the extent of being suitable for dating several legal cases.[8]

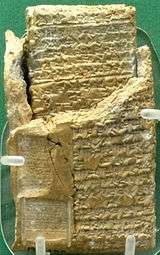

Niqmi-Epuh Seal

The seal of Niqmi-Epuh includes his name written in cuneiform inscription. The king is depicted wearing a crown, facing two goddesses, one in Syrian dress, while and the other is wearing Babylonian dress.[9]

Death and succession

Niqmi-Epuh died ca. 1675 BC. He seems to have a number of sons, including Irkabtum who succeeded him immediately, prince Abba-El,[10] and possibly Yarim-Lim III.[11] Hammurabi III the last king before the Hittites conquest might have been his son too.[12]

King Niqmi-Epuh of Yamhad (Halab) Died: 1675 BC | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Yarim-Lim II |

Great King of Yamhad 1700 – 1675 BC |

Succeeded by Irkabtum |

References

Citations

- prof : Ahmad Arhim Hebbo. History of Ancient Levant (part 1) Syria.

- Douglas Frayne. Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 792.

- Horst Klengel. Syria, 3000 to 300 B.C. p. 62.

- THOMAS, D. WINTON. Archaeology and Old Testament study: jubilee volume of the Society for Old Testament Study, 1917-1967. p. 121.

- Direction Générale des Antiquités et des Musées., 1999. Annales archéologiques Arabes Syriennes, Volume 43. p. 174.

- Horst Klengel. Syria, 3000 to 300 B.C. p. 62.

- Akadémiai Kiadó, 1984. Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Volume 30. p. 12.

- James Bennett Pritchard,Daniel E. Fleming. The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. p. 197.

- Dominique Collon. Ancient Near Eastern Art. p. 96.

- Michael C. Astour. Hittite history and absolute chronology of the Bronze Age. p. 18.

- wilfred van soldt. Akkadica, Volumes 111-120. p. 105.

- Douglas Frayne. Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). p. 794.