New Zealand sand flounder

The New Zealand sand flounder (Rhombosolea plebeia) is a righteye flounder of the genus Rhombosolea, found around New Zealand in shallow waters down to depths of 100 m.

| New Zealand sand flounder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Pleuronectiformes |

| Family: | Pleuronectidae |

| Genus: | Rhombosolea |

| Species: | R. plebeia |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhombosolea plebeia (Richardson, 1843) | |

| Synonyms | |

Common names

New Zealand dab, pātiki, diamond, tinplate, square flounder.[2]

Description

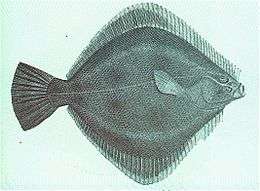

Like other flatfish, the larval sand flounder begins its life with an eye on each side of its head and a round body shape, swimming upright through the midwater.[3] As it grows out of this larval stage entering the juvenile stage one eye moves to the right side leaving the other blind and it takes on a flat diamond shape swimming flat/parallel to the ground. On the right side, the fish is a greenish brown dark colour or grey with faint mottling and on the left side (the side it lies on without eyes) it is white.[4] The average length of an adult sand flounder is 25–35 cm with the maximum being 45 cm.[5] In the day time, they lie on the seabed camouflaged almost perfectly in sand or mud; they have special pigment cells on their skin that can change colour to match their background, their protruding blue-green eyes being their only giveaway.[6] They swim in a flowing style with an undulating movement of the side fins and when threatened by predators their tail is used for propulsion. Technically the adult swims on its side with the continuous dorsal fin fringing one edge of its diamond shaped body and its extended anal fin on the other. It has no swim bladder and only leaves the seabed for courtship and spawning activities.[7]

Distribution

Natural global range

Sand flounder are native to New Zealand so they are not found anywhere else in the world but they are found all over New Zealand.[8]

New Zealand range

New Zealand sand flounder is found in a majority of coastal waters around New Zealand. Its largest population is found at Tasman Bay and on the East Coast of the South Island.[9] Around New Zealand they can be found in harbours, inlets, bays and open water.[8]

Habitat preferences

They prefer coastal areas and are found in waters up to 50m deep but rarely deeper.[9] They can be found in harbours, inlets, bays and open water. They are common on mudflats but seem to have no preference of bottom substrate as they are also found on sand, clay, pebbles and gravel bottoms.[8] They also can be found in estuaries.[10] When they are juveniles they are found in sheltered inshore areas such as estuaries, mudflats and sand flats where they will stay for around two years. They also prefer a temperate climate.[11]

Life cycle

The geographic location of the New Zealand sand flounder determines its spawning period. In the north, it has a long spawning period from March to December. In the south, spawning largely occurs in the spring.[12] A study in the Hauraki Gulf found sand flounder lay between 100,000 and 500,000 eggs when spawning.[9] The variation in the number of eggs laid was attributed to the difference in size of the female laying the eggs.[9]

After a period of time dependent on the temperature of the water (usually around a week), the larval sand flounder hatches. Larval sand flounders have a large yolk sac attached to their underside, providing nutrients to the fish until it is large enough to feed itself. At this stage, they are less than a half a centimetre in length. They have an eye on each side of their head and swim upright, as most fish do. As sand flounders grow they begin utilising external food sources such as seaweed spores and algae, and as they grow further, small shrimp and plankton.

The extra nutrients they receive from these new food sources enables them to grow to around one and a half centimetres by the time they are three weeks old. Above each eye of the sand flounder is a bar of cartilage, and at this stage of its development the cartilage above the left eye is absorbed and the eye begins to move from the side of the head, until it is next to the right eye. The unusual, twisted shape of the mouth of the sand flounder is due to the movement of the skull and bones as the left eye migrates to the right side of the body. While this slow process is occurring, the sand flounder begins to grow out to the side and flatten, losing its rounded shape. This metamorphism makes swimming as the larval sand flounder was able to difficult and exhausting.[13] The now juvenile sand flounders sink to the bottom and begin swimming as adult flatfish do, by undulating their side fins and for rapid acceleration, use their tail.[12]

The juvenile R. plebeia migrate to the shallow water of the estuaries and mudflats where they remain until they mature at two years old. Once R. plebeia reach a mature age and size, they migrate to deeper water of around 30 to 50 metres deep to spawn.[12][2] After this first migration, they continue to migrate from shallow waters (0-50m) in spring and summer to deeper waters (50-100m) in autumn and winter. Male R. plebeia are smaller than female R. plebeia, maturing at a length of 10 cm, but can grow to 15–17 cm. The females grow faster, with mature size being 16–20 cm long, but they grow to 23–24 cm by age two. By age of three, female sand flounders grow to an average size of 30 cm. The average life span of flounder is three to four years.[12] This equates to being able to have two years of spawning.

Diet and foraging

The sand flounder feeds off a yolk-sac attached to its under surface until they are capable of fending for themselves. As an adult it is adapted to feed best at night on sand or mud. They are ambush predators, going unnoticed by camouflage and then attacking their prey when it comes near. They eat a variety of bottom-dwelling invertebrates such as crabs, brittlestars, shrimps, worms, whitebait, shellfish and tiny fishes located by touch and vision.[5] They also ingest mud detritus and seaweed while feeding.[3]

Predators, parasites, and diseases

Sand flounder are a very important commercial fish in New Zealand which means that humans are a predominant predator for them.[8] Flat fishes including the sand flounder are good at camouflage which allows them to hide well from any predators. They are good at it because when they settle they wiggle their marginal fins throwing up a shower of sand or mud which lands on them and makes them almost undetectable.[14] In saying this sand flounders still get preyed on, some predators include tope, spined dogfish, Maori chief, ling and toadfish.[15] In a study done in the Avon-Heathcote Estuary they found that sand flounder were hosts of many different parasites including Nerocila orbignyi and Heteracanthocephalus peltorhamphi which were both found in less than one percent of fish sampled. They found trematode's in 24% of the sand flounder, Hedruris spinigera in 6%, and fungal patches on 13%.[16]

Other

The New Zealand sand flounder is a popular fish caught by humans to eat. Recreational fishers catch the fish usually in beach seines, setnets or with spears.[5] The Maori used wooden spears to catch what they called ‘Patiki’ at night on mud flats. They would attract the ‘Patiki’ by light from a torch made of pine, spearing them with ease.[3] Commercially sand flounder are fished by trawl and setnet.[5] Sand flounder is very easy to cook and there are many ways to cook and serve it depending on preferences. At its simplest, it can be served beautifully after washing, drenching in flour and frying each side in a medium hot pan with oil/butter until the skin is crisp.[17] At the moment, sand flounder numbers are decreasing, but there is no evidence to show that the decline is rapid and they are still common in areas where they are found. So, because of this, they have been classed as Least Concern on the red list category and criteria. For these reasons, there is no current conservation effort to try save sand flounder, but as it is one of the most important commercial fishes in New Zealand ongoing research on the harvest levels and population numbers of this species is needed to make sure that they do not leave the Least Concern class and so that they know if they do, conservation efforts can be made.[8]

References

- Munroe, T.A. (2010). "Rhombosolea plebeia (errata version published in 2017)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T154914A115251972. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T154914A4666185.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help) Downloaded on 26 March 2018.

- Banks, D.; Crysell, S.; Garty, J.; Paris, S.; Selton, P. (2007). A Guide Book to New Zealand Commercial Fish Species 2007 Revised Edition. New Zealand: Seafood Industry Council Ltd.

- Graham, D. H. (1953). A Treasury of New Zealand Fish. Wellington: Hutcheson, Bowman and Stewart Ltd.

- Paul, L. (1986). New Zealand Fishes. Auckland: Reed Books.

- Paul, L. (1997). Marine Fishes of New Zealand. Auckland: Reed Books.

- Doak, W. (2003). Sea Fishes of New Zealand. (B. O'Flaherty, Ed.) New Holland Publishers Ltd.

- Paul, L., & Moreland, J. (1993). Handbook of New Zealand Marine Fishes. Auckland: Reed Books.

- Munroe T.A. (2010) | Rhombosolea plebeia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010

- Colman, J. (1973). "Spawning and Fecundity of two flounder species in the Hauraki gulf, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 7 (1–2): 21–43. doi:10.1080/00288330.1973.9515454.

- McDowall R.M. (1976) The Role of Estuaries in the Life Cycles of Fishes in New Zealand. New Zealand Ecological Society 26.

- Torres A. Rhombosolea plebeia summary page

- Francis, M. (2012). Coastal Fishes of New Zealand, Identification, Biology, Behaviour. Craig Potton Publishing.

- Graham, D. (1956). A Treasury of New Zealand Fishes. A.H. & A.W. Reed.

- Manikiam J.S. Manikiam (1969) A Guide to Flatfishes (Order Heterosomata) of New Zealand Tuatara

- D.H. Graham (1939) Food of the Fishes of Otago Harbour and Adjacent Sea Royal Society of New Zealand

- Webb B.F. Webb (1973) Fish populations of the Avon‐Heathcote Estuary (Breeding and Gonad Maturity) New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research

- Enderby, J., & Enderby, T. (2012). Know Your New Zealand Fishes. (B. O'Flaherty, Ed.) New Holland Publishers Ltd.

Other references

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "Rhombosolea plebeia" in FishBase. March 2006 version.

- Tony Ayling & Geoffrey Cox, Collins Guide to the Sea Fishes of New Zealand, (William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand 1982) ISBN 0-00-216987-8