New Zealand long-tailed bat

The New Zealand long-tailed bat (Chalinolobus tuberculatus), also known as the long-tailed wattled bat or pekapeka-tou-roa (Māori), is one of 15 species of bats in the genus Chalinolobus variously known as "pied bats", "wattled bats" or "long-tailed bats". It is one of the two surviving bat species endemic to New Zealand, but is closely related to five other wattled or lobe-lipped bats in Australia and elsewhere.

| New Zealand long-tailed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Chalinolobus |

| Species: | C. tuberculatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Chalinolobus tuberculatus (Forster, 1844) | |

Description

The long-tailed bat is a small brown bat (weighing 8–12 g) with a long tail connected by a patygium to its hind legs: this feature distinguishes it from New Zealand's other bat species, the short-tailed bat. The bat's echolocation calls include a relatively low frequency component which can be heard by some people. It can fly at 60 kilometres per hour, and has a very large home range (100 km²). Life expectancy for this species is unknown, though it exceeds nine years.[2] It is the main host of the New Zealand bat flea. This species has a highly variable body temperature and rate of metabolism.[3]

Diet

Long-tailed bats hunt by hawking, or capturing and consuming aerial insects while flying.[4] Flies are their most significant food source, with moths and beetles also important.[5] The bat is an insect generalist, consuming insects that are abundant in the landscape.[5]

Roosting

New Zealand long-tailed bats are selective when choosing roost trees. Preferred roosts are located at low altitude at the bottoms of valleys, less than 500 metres (0.31 mi) from the woodland edge.[6] The bats prefer tall roosts of large diameter located in areas of lower tree density, particularly live red beech trees or snags.[6] Three-quarters of roost trees identified in the South Island were at least one hundred years old.[6] The bats roost in small cavities within the trees that have high temperatures and humidity.[7]

Reproduction

Males and females are capable of successful reproduction after their first year, and most females first give birth at age two or three.[2] Mating is thought to occur in February and March, shortly before hibernation, based on the proportion of males with swollen epididymides at this time.[2] Females give birth to a single pup during the New Zealand summer (December and January) and provide sole care for their young, gathering with other females in maternity roosts of up to 120 individuals; small numbers of adult males and non-reproductive females are present in the roosts as well.[2] These subcolonies move to new trees almost every day, breaking apart into smaller groups or reforming into larger ones. In some areas limestone caves are also used, but mainly as a night roost between feeding bouts. Pups fledge about 40 days after birth.[2] Pups are likely weaned within ten days of fledging.[2]

Conservation

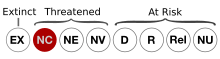

The species first gained legal protection under the New Zealand Wildlife Act 1953.[8] The New Zealand long-tailed bat has been classified in New Zealand by the Department of Conservation as "Nationally Critical" with the qualifier "Conservation Dependent" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System as a result of a predicted decline of greater than 70%.[1] The bats' preference for large, old roost trees makes them at risk from habitat destruction through logging.[9] They may also be at risk from windfarms, unless successfully relocated.[10]

References

- O'Donnell, Colin F. J.; Borkin, Kerry; Lloyd, Brian; Parsons, Stuart; Hitchmough, Rod; Christie, J. E. (March 2018). Conservation status of New Zealand bats, 2017. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 3. ISBN 9781988514529. OCLC 1029247050.

- O'Donnell, C. F. (2002). "Timing of breeding, productivity and survival of long-tailed bats Chalinolobus tuberculatus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in cold-temperate rainforest in New Zealand". Journal of Zoology, 257(03), 311–323.

- McNab, Brian K.; O'Donnell, Colin (2018). "The behavioral energetics of New Zealand's bats: Daily torpor and hibernation, a continuum". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 223: 18–22. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.05.001. PMID 29746908.

- Rockell, G., Littlemore, J., & Scrimgeour, J. (2017). Habitat preferences of long-tailed bats Chalinolobus tuberculatus along forested riparian corridors in the Pikiariki Ecological Area, Pureora Forest Park. DOC Research and Development Series 349.

- Gurau, A.L. (2014). The diet of the New Zealand long-tailed bat, Chalinolobus tuberculatus. Masters in Zoology thesis, Massey University.

- Sedgeley, J. A., & O'Donnell, C. F. (1999). Roost selection by the long-tailed bat, Chalinolobus tuberculatus, in temperate New Zealand rainforest and its implications for the conservation of bats in managed forests. Biological Conservation 88(2), 261–276.

- Sedgeley, J. A. (2001). Quality of cavity microclimate as a factor influencing selection of maternity roosts by a tree‐dwelling bat, Chalinolobus tuberculatus, in New Zealand. Journal of Applied Ecology, 38(2), 425–438.

- O’Donnell, C. F. (2000). Conservation status and causes of decline of the threatened New Zealand long‐tailed bat Chalinolobus tuberculatus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Mammal Review, 30(2), 89–106.

- Sedgeley, J. A. (2003). Roost site selection and roosting behaviour in lesser short‐tailed bats (Mystacina tuberculata) in comparison with long‐tailed bats (Chalinolobus tuberculatus) in Nothofagus forest, Fiordland. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 30(3), 227–241.

- "Final Report and Decision of the Board of Inquiry into the Hauāuru mā Raki Wind Farm and Infrastructure Connection to Grid" (PDF). Ministry for the Environment. May 2011.

External links

- NZ Department of Conservation Bat Site

- DOC 1995 Threatened Species Recovery Plan (distribution map on page 4)

- Long-tailed bats discussed on RNZ Critter of the Week, 17 November 2017