Neelum District

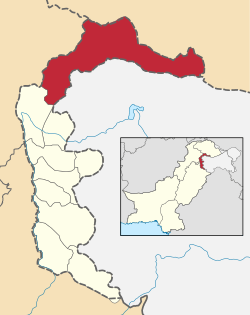

Neelum District[1] (also spelt as Neelam; Urdu: ضلع نیلم), is the northernmost district of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Taking up the larger part of the Neelam Valley, the district has a population of 191,000 (as of 2017).[2] It was badly affected by the 2005 Kashmir earthquake.[3]

Neelum District ضلع نیلم Neelam District | |

|---|---|

Verdant forests predominate in the Neelum Valley | |

| |

| Coordinates: 34.5891°N 73.9106°E | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Territory | Azad Kashmir |

| Headquarters | Athmuqam |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,621 km2 (1,398 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 191,251 |

| • Density | 53/km2 (140/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| Number of Tehsils | 2 (Athmuqam, Sharda) |

Location

The Neelum River was known before Partition as Kishan Ganga and was subsequently renamed after the village of Neelam.[4] It flows down from the Gurez Valley in Indian Jammu and Kashmir and roughly follows first a western and then a south-western course until it joins the Jhelum River at Muzaffarabad. The valley is a thickly wooded region with an elevation ranging between 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and 7,500 feet (2,300 m), the mountain peaks on either side reaching 17,000 feet (5,200 m).[5] Neelum Valley is 144 kilometres (89 mi) long.[6]

Most of the valley is taken up by the Neelum District(Urdu: ضلع نیلم). The district is bordered on the south-west by Muzaffarabad District, which also encompasses the lower reaches of the valley; to the north-west beyond the mountains lies the Kaghan Valley in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's Mansehra District; to the north and north-east are the Diamer, Astore and Skardu districts of Gilgit-Baltistan. To the south and east are the Kupwara and Bandipora districts of Indian Kashmir. The Line of Control runs through the valley – either across the mountains to the south-east, or in places right along the river, with several villages on the left bank falling on the Indian side of the border.[7]

Administration

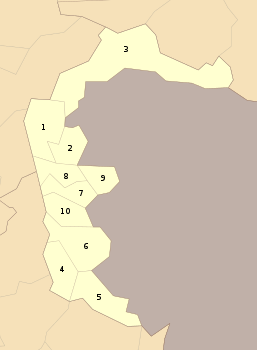

Neelum District was part of Muzaffarabad District until 2005.[5] It is made up of two tehsils[8]: Athmuqam, which contains the district headquarters, and Sharda. Neelum District is the largest district of Azad Kashmir by area. The valley extends for approximately 200 kilometers along the Neelum River. This is a generally poor region, reliant on subsistence agriculture and handicrafts, with tourism growing in importance in recent years.[9] According to the Alif Ailaan Pakistan District Education Rankings 2015, Neelum is ranked 33 out of 148 districts in terms of education. For facilities and infrastructure, the district is ranked 136 out of 148.[10]

Languages

Several languages are spoken natively in the district. The predominant one is Hindko. It is the language of wider communication in the area and is spoken at a native or near-native level by almost all members of the other language communities, many of whom are abandoning their language and shifting to Hindko.[11] This language is usually called Parmi (or Parimi, Pārim), a name that likely originated in the Kashmiri word apārim 'from the other side', which was the term used by the Kashmiris of the Vale of Kashmir to refer to the highlanders, who spoke this language. The language is also sometimes known as Pahari, although it bears a closer resemblance to the Hindko of neighbouring Kaghan Valley than to the Pahari spoken in the Murree Hills.[12] Unlike other varieties of Hindko, Pahari or Punjabi, it has preserved the voiced aspirated consonants at the start of the word: for example, gha 'grass' vs. Punjabi kà, where the aspiration and voicing have been lost giving rise to a low tone on the following vowel. This sound change however, is currently spreading here as well, but it has so far only affected the villages situated along the Neelam highway.[11] This variety of Hindko is also spoken in nearby areas of India-administered Kashmir. Since Partition, the language varieties on either side of the Line of Control have diverged in a number of ways. For example, in the Neelam Valley, there is a higher proportion of Urdu loanwords, while the variety spoken across the Line of Control has retained more traditional Hindko words.[13]

The second most widely spoken language of the Neelam Valley is Kashmiri. It is the majority language in at least a dozen or so villages, and in about half of these it is it the sole mother tongue. It is closer to the variety spoken in northern Kashmir (particularly Kupwara) than to the Kashmiri of the city of Muzaffarabad.[14]

The third-largest ethnic, though not linguistic,[15] group are the Gujjars, whose villages are scattered throughout the valley. Most of them have switched to Hindko, but a few communities continue using the Gujari language at home. Gujari is more consistently maintained among the Bakarwal, who travel into the valley (and beyond into Gilgit-Baltistan) with their herds in the summer and who spend the winters in the lower parts of Azad Kashmir and in Punjab.[16]

In the upper end of the valley, there are two distinct communities speaking two different varieties of Shina (locally sometimes called Dardi). One of them is found at Taobutt and the nearby village of Karimabad (formerly known as Sutti) near the border with India. Its speakers claim that their variety of Shina is close to the one spoken further up the valley in Indian Gurez. The community is bilingual in Kashmiri and is culturally closer to the neighbouring Kashmiri communities than to the other Shina group, who inhabit the large village of Phulwei 35 kilometres (22 mi) downstream. The Shina people of Phullwei claim to have originally come from Nait near Chilas in Gilgit-Baltistan.[17]

A Pashto dialect is spoken in two villages (Dhaki and Changnar) that are situated on the Line of Control. Because of cross-border firing since the early 1990s, there has been large-scale migration away from these villages. The local dialect is not completely intelligible with the ones spoken in the rest of Pakistan.[18]

One language that is unique to the Neelam Valley is the endangered Kundal Shahi. It is spoken by some of the inhabitants of the Kundal Shahi village near Athmuqam.[19]

Additionally, Urdu is spoken by the formally educated and, like English, is used as a medium of instruction in schools.[20]

Education

According to Pakistan District Education Ranking 2017, a report released by Alif Ailaan, the district of Neelum stands at number 58 nationally in the ranking related to education with an education score of 60.87. Neelum is lowest-ranked district in all of Azad Kashmir.

See also

References

- AJK at a glance 2015 (PDF) (Report). p. 22.

-

- "Census 2017: AJK population rises to over 4m". The Nation. 26 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "rmc.org.pk - Earthquake Map". Archived from the original on 21 September 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 65. The village is 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) upstream from Athmuqam. An alternative etymology links the name to the colour of the river: "sapphire". (Faruqi 2016)

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 65.

- "Length of Neelum Valley". en.dailypakistan.com.pk. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Baart & Rehman 2005, p. 4; Akhtar & Rehman 2007, pp. 65–66.

- "Tehsils of Neelum District on AJK map". ajk.gov.pk. AJK Official Portal. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Faruqi 2016.

- "Individual district profile link, 2015". Alif Ailaan. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 69.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 68. The variant Parimi as well as the local use of the terms Pahari and Hindko are from Rehman (2011, p. 227).

- Sohail, Rehman & Kiani 2016, p. 108.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 70. Additionally, Kashmiri speakers are better able to understand the variety of Srinagar than the one spoken in Muzaffarabad.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 72.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, pp. 71–72.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, pp. 72–74.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, pp. 74–75.

- Baart & Rehman 2005.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, pp. 75–78.

Bibliography

- Akhtar, Raja Nasim; Rehman, Khawaja A. (2007). "The Languages of the Neelam Valley". Kashmir Journal of Language Research. 10 (1): 65–84. ISSN 1028-6640.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baart, Joan L. G.; Rehman, Khawaja A. (2005). "A first look at the language of Kundal Shahi in Azad Kashmir". SIL Electronic Working Papers. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Faruqi, Sama (18 August 2016). "Neelum Valley: The sapphire trail". Herald (Pakistan). Retrieved 8 January 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rehman, Khawaja A. (2011). "Ergativity in Kundal Shahi, Kashmiri And Hindko". In Turin, Mark; Zeisler, Bettina (eds.). Himalayan languages and linguistics: studies in phonology, semantics, morphology and syntax. Brill's Tibetan studies library, Languages of the greater Himalayan region. Leiden : Biggleswade: Brill. pp. 219–234. ISBN 978-90-04-19448-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sohail, Ayesha; Rehman, Khawaja A.; Kiani, Zafeer Hussain (2016). "Language divergence caused by LoC: a case study of District Kupwara (Jammu & Kashmir) and District Neelum (Azad Jammu & Kashmir)". Kashmir Journal of Language Research. 19 (2): 103–120. ISSN 1028-6640.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Neelum Valley Tour

- Attractions and Places to visit in Neelum Valley

- http://emergingpakistan.gov.pk/travel/place-to-visit/azad-kashmir/neelum-valley/

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neelum District. |