Hooded vulture

The hooded vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus) is an Old World vulture in the order Accipitriformes, which also includes eagles, kites, buzzards and hawks. It is the only member of the genus Necrosyrtes, which is sister to the larger Gyps genus, both of which are a part of the Aegypiinae subfamily of Old World vultures.[2] It is native to sub-Saharan Africa, where it has a widespread distribution with populations in southern, East and West Africa.[3][4] It is a scruffy-looking, small vulture with dark brown plumage, a long thin bill, bare crown, face and fore-neck, and a downy nape and hind-neck. Its face is usually a light red colour. It typically scavenges on carcasses of wildlife and domestic animals. Although it remains a common species with a stable population in the lower region of Casamance, some areas of The Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau, other regions such as Dakar, Senegal, show more than 85% losses in population over the last 50 years[4][5]. Threats include poisoning, hunting, loss of habitat and collisions with electricity infrastructure, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has rated its conservation status as "critically endangered" in their latest assessment (2017).[5] The highest current regional density of hooded vultures is in the western region of The Gambia[6]

| Hooded vulture | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| in Gambia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Necrosyrtes Gloger, 1841 |

| Species: | N. monachus |

| Binomial name | |

| Necrosyrtes monachus (Temminck, 1823) | |

Etymology

The common name "hooded vulture" stems from the fact that the vulture has a small patch of downy feathers that runs along the back of its neck to the crown of its head, making it look like it is wearing a fluffy, cream-colored hood.[7] The scientific name, Necrosyrtes monachus, can be broken down into 3 sections: "necro", since it feeds on carrion; "syrtes" which means "quicksand" or "bog" and "monachus" which is Latin for "monk" and relates to the hood of the vulture.[8]

Description

Appearance

The hooded vulture is a typical vulture, with a head that is usually pinkish-white, but flushes red when agitated,[9] and a grey to black "hood". It has fairly uniform dark brown body plumage. It has broad wings for soaring and short tail feathers. This is one of the smaller Old World vultures. They are 62–72 cm (24–28 in) long, have a wingspan of 155–180 cm (61–71 in) and a body weight of 1.5–2.6 kg (3.3–5.7 lb).[10] Both sexes are alike in appearance, although females often have longer eyelashes than males. Juveniles look like adults, only darker and plainer, and body feathers have a purplish sheen.[8]

Voice

Usually silent, but gives a shrill, sibilant whistle during copulation, and thin squealing calls both at nests and carcasses.[8]

Distribution

Although hooded vultures have relatively small home ranges, they are widely distributed across Africa. It occurs in Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau, The Gambia, Niger and Nigeria in West Africa; in East Africa it is found in Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia; in southern Africa it has been recorded in northern Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa.[5]

Within South Africa, the species is essentially restricted to the Kruger National Park and surrounding protected areas in Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces, though vagrants have been recorded further west in Kwa-Zulu Natal and Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park.[11]

Ecology

.jpg)

Like other vultures hooded vultures are scavengers, feeding mostly from carcasses of dead animals and waste which they find by soaring over savanna and around human habitation, including waste tips and abattoirs[4]. They do however also feed on insects, and conglomerate in large numbers during insect emergences, for example termite emergences where they associate with Steppe Eagles[5][8].They are non-specialised, highly versatile scavengers and are commensal with humans in West Africa.[12] They often move in flocks (50-250 individuals) in West Africa, especially when foraging at abattoirs or elephant carcasses[8], while in southern Africa they are solitary and secretive, making them hard to spot when nesting[11]. They are known to follow scavenging African wild dogs and hyaenas.[8]

This vulture is typically unafraid of humans, and frequently gathers around habitation. It is sometimes referred to as the “garbage collector” by locals. In Ghanaian universities, a significantly higher number of hooded vultures exist in the residential parts of the campus relative to the non-residential parts, and densities are correlated with the academic calendar, with numbers of individuals increasing during school terms.[13] 45% of students at these campuses are defecated on by hooded vultures at least once a month, according to interviews.[13]

Southern African hooded vulture populations have smaller home ranges than most other Old World vulture species for which data exists, though less is known about home ranges of East and West African populations[3]. They are most active during the day, and their ranges are smaller in the dry breeding season, when their movement is constrained by a nest site location to which they must return regularly to incubate their eggs and provision their fledglings[3]. In both the northern and southern hemisphere populations, breeding takes place in the dry summer season.[5]

They prefer to build nests in well-foliaged trees along watercourses, with the nest placed a prominent fork within the tree canopy at an average height of over 15m.[11] They have however also been observed in a variety of biomes, some where tall trees are rare. They have been recorded in open grasslands, deserts, wooded savanna, forest edges and along coasts[5]. They tend to occur in higher densities where populations of larger Gyps vultures are low or nonexistent [14]. It occurs up to 4,000 m, but is most numerous below 1,800 m.[5]

Hooded vultures lay a clutch of one egg, and the incubation period lasts 46-54 days, followed by a fledging period of 80-130 days. Young are dependent on their parents for a further 3-4 months after fledging[14]. Measurements of nesting success at the Olifants River Private Nature Reserve, South Africa showed success of 0.44-0.89 offspring per pair per year in 2013 and 0.50-0.67 offspring per pair per year in 2014.[5]

Population trends

While the populations in Gambia are relatively stable, it is declining almost everywhere else in its range at an average rate of 83% (range 64-93%) over 53 years (3 generations).[5][15] Its total population is estimated at a maximum of 197 000 individuals.[16] Some declines have been reported to have occurred in only 20 years, almost approaching the speed and extent of the Asian vulture crisis of the 1990s.[15] The highest regional density of hooded vultures is in western Gambia.[6]

Status and threats

The species has been uplisted from its previous IUCN status of endangered to critically endangered, since the species is going through a very steep decline in population, owing to various factors including poisoning, hunting, habitat loss and degradation of habitat. Hunting is the most well-known threat to the species, however, poisoning has been shown to have the highest impact on the population. Poisoning of the species has been both unintentional and intentional, with unintentional poisoning being caused through the poisoning of other animals which the species feeds on. Hunting on the other hand is caused by vultures being used by people in traditional medicine and cultural beliefs and as a food source, particularly in West and southern Africa.[17][15] Researchers interviewed vendors in street markets in northern Nigeria who were selling parts or entire carcasses of hooded vultures as well as other African vulture species (though hooded vultures made up 90% of vultures on sale). They found that 40% of traders were selling the vultures for spiritual healing and 25% for human consumption.[18]

Many West and southern African cultures believe vulture body parts cure a range of physical and mental illnesses, improve success in gambling and business ventures, or increase intelligence in children[15]. Consumption of vultures as bushmeat in Nigeria and Ivory Coast may be of regional concern, but smoked vulture meat is traded and consumed internationally[15]. Secondary poisoning with carbofuran pesticides at livestock baits being used to poison mammalian predators is also an issue in East Africa[5].

On the 20th of June 2019, the carcasses of 468 white-backed vultures, 17 white-headed vultures, 28 hooded vultures, 14 lappet-faced vultures and 10 cape vultures), altogether 537 vultures, besides 2 tawny eagles, were found in northern Botswana. It is suspected that they died after eating the carcasses of 3 elephants that were poisoned by poachers, possibly to avoid detection by the birds, which help rangers to track poaching activity by circling above where there are dead animals.[19][20][21][22]

The species may also be threatened by avian influenza (H5N1), from which it appears to suffer some mortality and which it probably acquires from feeding on discarded dead poultry.[23] Another suggested cause of decline is the decline in the number of trees preferred by hooded vultures for nesting, such as Ceiba pentandra in Senegal.[5]

Conservation action

Raptors are protected in many West African and Northeastern countries and in South Africa under the United Nations Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), in the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Birds of Prey in Africa and Eurasia (the ‘Raptors MoU’).[24] This plan includes the Hooded vulture.[25]

Systematic monitoring and protection schemes for African raptors, including the hooded vulture, exist and some populations occur within protected areas[5]. It has been suggested that the best way to slow the decline of vulture populations in Africa, and avoid a massive decline on the scale of the Asian vulture crisis of the 1990s in which populations declined 95% because of the veterinary drug Diclofenac used in livestock whose carcasses were fed on by vultures, pesticides and poisons need to be regulated and limited by governments in countries where the hooded vulture occurs[15] .

Gallery

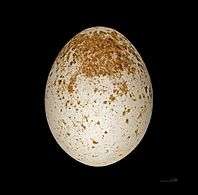

Egg

Egg Head

Head Juvenile, Sabi Sand Game Reserve, South Africa

Juvenile, Sabi Sand Game Reserve, South Africa_juvenile.jpg) Juvenile

Juvenile

Gambia

References

- BirdLife International 2017. Necrosyrtes monachus (amended version of 2017 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22695185A118599398. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22695185A118599398.en. Downloaded on 22 April 2020.

- Lerner, Heather R.L.; Mindell, David P. (2005). "Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (2): 327–346. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.010. PMID 15925523.

- Reading, Richard P.; Bradley, James; Hancock, Peter; Garbett, Rebecca; Selebatso, Moses; Maude, Glyn (2019-01-02). "Home-range size and movement patterns of Hooded Vultures Necrosyrtes monachus in southern Africa". Ostrich. 90 (1): 73–77. doi:10.2989/00306525.2018.1537314. ISSN 0030-6525.

- Wim C. Mullié ... (2017), "The decline of an urban Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus population in Dakar, Senegal, over 50 years", Ostrich, 88 (2): 131–138, doi:10.2989/00306525.2017.1333538

- "The IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species: Hooded vulture". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Jallow, M., Barlow, C., Sanyang, L... (2016). "High population density of the Critically Endangered Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus in Western Region, The Gambia, confirmed by road surveys in 2013 and 2015". Malimbus. 38: 23–28 – via ResearchGate.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Hooded Vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus) in Explore Raptors: Facts, habitat, diet | The Peregrine Fund". www.peregrinefund.org. Retrieved 2019-07-31.

- Hockey, PAR; Dean, WRJ; Ryan, PG (2005). Roberts Birds of Southern Africa: 7th Edition. Cape Town, South Africa: Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund. p. 486.

- Sinclair, Ian; Hockley, Phil; Tarboton, Warwick; Ryan, Peter (2011). SASOL birds of Southern Africa. Struik Nature. ISBN 978-1-77007-925-0.

- "Hooded Vulture". Oiseaux-Birds.com. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- Roche, Chris (2006-04-01). "Breeding records and nest site preference of Hooded Vultures in the greater Kruger National Park". Ostrich. 77 (1–2): 99–101. doi:10.2989/00306520609485515. ISSN 0030-6525.

- Barlow, Clive; Filford, Tony (2013). "Road counts of Hooded Vultures Necrosyrtes monachus over seven months in and around Banjul, coastal Gambia, in 2005". Malimbus. 35: 50–55.

- Gbogbo, F.; Awotwe-Pratt, V.P. (March 2008). "Waste management and Hooded Vultures on the Legon Campus of the University of Ghana in Accra, Ghana, West Africa". Vulture News. 58: 16–22.

- Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D.A. (2001). Raptors of the World. A&C Black.

- Ogada, Darcy; Shaw, Phil; Beyers, Rene L.; Buij, Ralph; Murn, Campbell; Thiollay, Jean Marc; Beale, Colin M.; Holdo, Ricardo M.; Pomeroy, Derek (2016). "Another Continental Vulture Crisis: Africa's Vultures Collapsing toward Extinction". Conservation Letters. 9 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1111/conl.12182. ISSN 1755-263X.

- Ogada, D. L.; Buij, R. (2011-08-01). "Large declines of the Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus across its African range". Ostrich. 82 (2): 101–113. doi:10.2989/00306525.2011.603464. ISSN 0030-6525.

- Henriques, Mohamed; Granadeiro, José Pedro; Monteiro, Hamilton; Nuno, Ana; Lecoq, Miguel; Cardoso, Paulo; Regalla, Aissa; Catry, Paulo; Margalida, Antoni (31 January 2018). "Not in wilderness: African vulture strongholds remain in areas with high human density". PLOS ONE. 13 (1): e0190594. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1390594H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190594. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5791984. PMID 29385172.

- Buij, Ralph; Saidu, Yohanna (2013-01-01). "Traditional medicine trade in vulture parts in northern Nigeria". Vulture News. 65 (1): 4–14–14. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v65i1.1. ISSN 1606-7479.

- "Over 500 Rare Vultures Die After Eating Poisoned Elephants In Botswana". Agence France-Press. NDTV. 2019-06-21. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- Hurworth, Ella (2019-06-24). "More than 500 endangered vultures die after eating poisoned elephant carcasses". CNN. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- Solly, Meilan (2019-06-24). "Poachers' Poison Kills 530 Endangered Vultures in Botswana". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- Ngounou, Boris (2019-06-27). "BOTSWANA: Over 500 vultures found dead after massive poisoning". Afrik21. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- Ducatez, Mariette F.; Tarnagda, Zekiba; Tahita, Marc C.; Sow, Adama; de Landtsheer, Sebastien; Londt, Brandon Z.; Brown, Ian H.; Osterhaus, Albert D.M.E.; Fouchier, Ron A.M. (2007). "Genetic Characterization of HPAI (H5N1) Viruses from Poultry and Wild Vultures, Burkina Faso". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (4): 611–613. doi:10.3201/eid1304.061356. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2725980. PMID 17553279.

- "Birds of Prey (Raptors) | Raptors". www.cms.int. Retrieved 2019-07-31.

- "Nations List 12 Vulture Species to Tackle Population Decline in Africa | Raptors". www.cms.int. Retrieved 2019-07-31.

4 http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=3372

- Sources

- BirdLife International (2012). "Necrosyrtes monachus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Necrosyrtes monachus. |

- Hooded vulture - Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds.