Navicella (mosaic)

The Navicella (literally "little ship") or Bark of St. Peter[2], of Old Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, was a large and famous mosaic by Giotto di Bondone that occupied a large part of the wall above the entrance arcade, facing the main facade of the basilica across the courtyard. It depicted the version from the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 14:24–32) of Christ walking on the water, the only one of the three gospel accounts where Saint Peter is summoned to join him.[3] It was almost entirely destroyed during the construction of the new Saint Peter's Basilica in the 17th century, but fragments were preserved from the sides of the composition, and what is effectively a new work, incorporating some original fragments, was restored to a position at the centre of the portico of the new building in 1675.[4]

The mosaic, designed to be seen from a distance, was extremely large. A full-scale copy in oil, commissioned by the Vatican from Francesco Berretta in 1628, after much of the work had already been lost round the edges, measures 7.4 by 9.9 metres (24 ft × 32 ft).[5] The full mosaic was probably about 9.4 by 13 metres (31 ft × 43 ft), with an inscription in Latin verse running below the image.[6]

Description

The mosaic was commissioned in 1298 by Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi, canon of St. Peter's, whose donor portrait was to the right of Christ's feet.[7] Giotto's mosaic therefore belonged to the preparations of St. Peters for the holy year in 1300. The date of the commission is attested by a document copied in the 17th century. There are no indications of a later dating, nor are there indications that Giotto's mosaic replaced an older one. [8] According to Stefaneschi's obituary of 1347, the work cost 2,200 florins.[9] In addition to an official document from 1298,[10] references to the work as by Giotto are found in a Vatican necrology entry for Cardinal Stefaneschi recording his death in 1343, and then the Latin chronicle of Giotto's home city Florence written in the late 14th century by Filippo Villani.[11]

It was rectangular, and positioned so that those leaving the basilica saw it across the courtyard outside the church, and passed under it if they left by the main route.[12] A figure of a man fishing on the shore to the left was thought to be a self-portrait of Giotto, as Vasari's Life records. The composition was dominated by the fishing boat with its large sail, which represented a metaphor of the "Ship of the Church", whose "captain" on earth was Saint Peter and his successors as Pope.[13] It was commissioned at a very difficult time for the Papacy, who were unable even to control the gangsterish nobility of Rome, and had therefore left the city, but the image promised that both church and Papacy were, with the help of Christ, "unsinkable".[14] Of the eleven figures still in the boat, it has been suggested that the one holding the tiller is (anachronistically in terms of the Gospels) Saint Paul.[15] In the sky, two almost naked classical style "wind god" figures blow through horns or funnels, one from each side, below pairs of haloed male figures. Giotto would have produced drawings for specialist mosaic workers to recreate on the wall; whether he had any further involvement as the work was created is unknown.

The subject is depicted elsewhere in medieval art of the period, and later works like frescos in the "Spanish Chapel" of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, and in the Brancacci Chapel by Masaccio (or perhaps his colleague Masolino), and one of the bronze relief panels on Ghiberti's north doors of the Florence Baptistery.[16] It was also used on Papal coins and medals, though usually with Peter in the boat, often as the only figure.[17] It was the only modern (post-classical) work described in Alberti's De Pictura.[18] Such a large depiction of a maritime scene was unprecedented in marine art, at least since classical times.

The arcade across the courtyard and its mosaic was at first unaffected by the protracted and complicated rebuilding of the main basilica, but in the 17th century the mosaic underwent a complicated series of four moves and restorations or remodellings in 1610, 1618, 1629 and 1674/75 which finally took it to its present size, condition and location above the main door inside the portico of the new church.[19]

Fragments

Only two bust-length figures of angels in roundels survive from the original;[20] one remains in the Vatican, while the other was given to the church of San Pietro Ispano in Boville Ernica in 1610, when the mosaic was first removed from its original place. The former is considerably restored (in 1924, 1950 and 1975–80), and was discovered underneath later work in 1911 (or 1924). The Boville Ernica fragment consisted of little original substance and was completely restored between 1888 and 1911.[21] Despite none of the copies of the original including these figures it is thought they were part of the original, probably in a border.[22] There are thought to be some patches of original work remaining in the mosaic still in St Peter's, which is now semi-circular with a straight bottom edge to fit into a lunette. Areas where original work seems to survive are in "the gilded edge of the ship, the sail blown by the wind, various sections of some apostles".[23]

Fragment in Boville Ernica, before restoration

Fragment in Boville Ernica, before restoration Fragment in Boville Ernica, after restoration

Fragment in Boville Ernica, after restoration Fragment in the Vatican, before restoration

Fragment in the Vatican, before restoration Fragment in the Vatican, after restoration

Fragment in the Vatican, after restoration

Style

The style of the work can now only be judged from the two angel fragments, restored as they are. Vasari's description emphasized the varied reactions of the figures in the boat as they saw Peter sinking below the waves, and the patient expression on the face of the fisherman on the shore, who, like Pieter Bruegel's ploughman in Landscape with the Fall of Icarus seems to ignore the dramatic scene on the water in concentrating on his own task. But, as Svetlana Alpers has shown, these were the terms in which Vasari tended to describe large history paintings he admired, though Alberti's description in De pictura also "treats ...[the work] as a psychological narrative".[24]

Modern scholars, working from the fragments, emphasize the influence of the major Roman artist of the day, Pietro Cavallini, who was also patronized by Cardinal Stefanesci, and of the Late Antique and Early Medieval works to be seen in Rome. According to John White: "The relatively schematic, linear quality of much late-thirteenth- and early-fourteenth-century work is wholly absent. The impressionistic technique and range of colour both derive from the fifth century. It is impossible to say how much this technique reflects the ideas of Giotto himself and how much those of the skilled mosaicists working under him. The two heads are, however, closely related both to the work of Cavallini, whose art still dominated the Roman scene, and to the basic type of physiognomy developed on the walls of the Arena Chapel."[25]

Copies

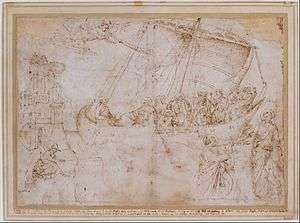

There are a number of records of the original design in drawings and prints—at least 17 are recorded. The earliest are a number of drawings attributed to the Florentine artist Parri Spinelli (c. 1387–1453), of which the most detailed is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and others are in Chantilly, Cleveland, Ohio and Bayonne. However, the variations between these, and other drawings by Spinelli of surviving works, show that he was in the habit of making rather loose interpretations of works that he recorded in drawings.[26] Most later copies date from after parts of the mosaic were already lost, and none form a complete record of the full design. Some prints, like an engraving by Nicolas Beatrizet of about 1559, are reversed (mirror-image) copies.[27]

Gospel account

Only in the account in Matthew 14:24–33 does Peter also leave the boat to walk on the waves:

But the boat was now in the midst of the sea, distressed by the waves; for the wind was contrary.

And in the fourth watch of the night he came unto them, walking upon the sea. And when the disciples saw him walking on the sea, they were troubled, saying, It is a ghost; and they cried out for fear. But straightway Jesus spake unto them, saying Be of good cheer; it is I; be not afraid. And Peter answered him and said, Lord, if it be thou, bid me come unto thee upon the waters. And he said, Come. And Peter went down from the boat, and walked upon the waters to come to Jesus. But when he saw the wind, he was afraid; and beginning to sink, he cried out, saying, Lord, save me. And immediately Jesus stretched forth his hand, and took hold of him, and saith unto him, O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt? And when they were gone up into the boat, the wind ceased.

And they that were in the boat worshipped him, saying, Of a truth thou art the Son of God.

Vision of St Catherine of Siena

On the evening of January 29, 1380, at the time of Vespers, Saint Catherine of Siena, who had been contemplating the mosaic for some hours, suddenly felt as if "the ship had fallen off and landed on her shoulders" with "unbearable weight". She understood that she was to give her life for the Church. She apparently never walked again, and died three months later.[28][29]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Navicella mosaic. |

- Parri Spinelli, "Free Copy of Giotto's Navicella", Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Forbes, Frances A.M. (2015). St. Catherine of Siena. Ravenio Books.

- Accounts of the miracle appear in three Gospels: Matthew 14:22–33, Mark 6:45–52 and John 6:16–21.

- "St Peter's"; Lubbock, 158; Tomei, 31; Nicholls, 162; Present image, from Bridgeman Art Library

- WGA

- Calvesi, 34; Tomei, 30

- Hösl, Ignaz, "Kardinal Jacobus Gaietani Stefaneschi: Ein Beitrag zur Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte des beginnenden vierzehnten Jahrhunderts," Berlin, 1908.

- Schwarz, Michael Viktor and Theis, Pia, Giottos Leben: mit einer Sammlung der Urkunden und Texte bis Vasari (Giottus Pictor I) Wien: Böhlau, 2004. Pg. 330-331.

- Tomei, 30

- Schwarz, Michael Viktor and Theis, Pia, Giottos Leben: mit einer Sammlung der Urkunden und Texte bis Vasari (Giottus Pictor I) Wien: Böhlau, 2004. Pg. 330-331.

- Murray, 77

- Calvesi, 34; Later print of the original location

- St Peter's

- Calvesi, 36; Paoletti & Radke, 65

- Nicholls, 164, reporting Köhren-Jansen, 1993

- Lubbock, 158–160

- Nicholls, 163; Examples from www.coinarchives.com

- Alpers, 199; Lubbock, 158

- See Kleinhenz 749, Capresi 36, Tomei, 31, though none give a coherent account of the process.

- Tomei, 31; Moioli et al., 244

- Schwarz, Michael Viktor and Theis, Pia, Giottos Werke (Giottus Pictor II) Wien: Böhlau, 2008, Pg. 262-263.

- Papacy, 6–7; Tomei, 31; Moioli et al., who give the date of discovery of the Vatican fragment as 1924, and the dates of subsequent work

- Vatican

- Alpers, 190–192, 199 (quoted); Lubbock, 158 quotes from Alberti

- White, 332 (quoted); see also Calvesi, 40, and Paoletti & Radke, 65

- Bean, no. 2 (New York); Dunbar, 104–110 (Cleveland)

- image on flickr of the Beatrizet; Unreversed print of 1567 Archived 2013-07-02 at Archive.today, by Mario Labacco, from Budapest.

- Papetros, 4

- Forbes, Frances A. Biograpy | St. Catherine of Siena.

References

- Alpers, Svetlana Leontief, "Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari's Lives", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 23, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1960), pp. 190–215, JSTOR, on Vasari's account

- Bean, Jacob, 100 European Drawings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1964, New York Graphic Society, New York, cat. no. 2, fig. no. 2,

- Calvesi, Maurizio; Treasures of the Vatican, Skira, Geneva, London and New York, 1962

- Dunbar, Burton Lewis and Olszewski, Edward J., Drawings in Midwestern Collections: A Corpus, Volume 1, 1996, University of Missouri Press, ISBN 0826210627, google books

- Keinhenz, Christopher, Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia, Volume 2, 2004, Routledge, ISBN 0415939291, google books

- Lubbock, Jules, Storytelling in Christian art from Giotto to Donatello, 2006, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300117272, google books

- "Moioli et al.": P. Moioli, C. Pelosi, C. Seccaroni, "The diagnostic analysis for the study and restoration of the mosaic fragment with an Angel from Giotto’s Navicella", Atti del Convegno "Riflessioni e trasparenze. Diagnosi e conservazione di opere e manufatti vetrosi", Ravenna 24–26 February 2009, Bologna 2010, pp. 267–278.PDF

- Murray, Peter, "Notes on Some Early Giotto Sources", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 16, No. 1/2 (1953), pp. 58–80, JSTOR

- Nicholls, Rachel, Walking on the Water: Reading Mt. 14:22 – 33 in the Light of Its Wirkungsgeschichte, 2008, BRILL, ISBN 9004163743, google books

- "Papacy": The Vatican Collections:The Papacy and Art (Catalogue of an Exhibition shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Art Institute of Chicago, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1983–84), no. 7 (Vatican angel roundel), 1982, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0870993216, google books

- Papetros, Spyros, On the Animation of the Inorganic: Art, Architecture, and the Extension of Life, 2012, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226645673, google books

- Paoletti, John T., and Radke, Gary M., Art in Renaissance Italy, 2005, Laurence King Publishing, ISBN 1856694399, google books

- "St Peter's": "Navicella" page on saintpetersbasilica.org

- Tomei, Alessandro, Giotto, Art Dossier Series, #120, 1998, Giunti Editore, ISBN 8809762673, google books

- White, John. Art and Architecture in Italy, 1250 to 1400, London, Penguin Books, 1966, 2nd edn 1987 (now Yale History of Art series). ISBN 0140561285

Further reading

- Köhren-Jansen, Helmtrud, Giottos Navicella, 1993, Volume 8 of Bibliotheca Hertziana Roma: Römische Studien der Bibliotheca Hertziana, Veröffentlichungen der Bibliotheca Hertziana (Max Planck Institute) in Rome/Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, ISBN 3884621033, (325 pp., the most recent monograph, in German)

- Oakeshott, Walter, The mosaics of Rome, from the third to the fourteenth centuries, 1967, Thames & Hudson, London (US: New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Conn.)