Nasal mucosa

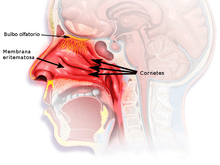

The nasal mucosa lines the nasal cavity. It is part of the respiratory mucosa, the mucous membrane lining the respiratory tract.[1][2] The nasal mucosa is intimately adherent to the periosteum or perichondrium of the nasal conchae. It is continuous with the skin through the nostrils, and with the mucous membrane of the nasal part of the pharynx through the choanae. From the nasal cavity its continuity with the conjunctiva may be traced, through the nasolacrimal and lacrimal ducts; and with the frontal, ethmoidal, sphenoidal, and maxillary sinuses, through the several openings in the nasal meatuses. The mucous membrane is thickest, and most vascular, over the nasal conchae. It is also thick over the nasal septum where increased numbers of goblet cells produce a greater amount of nasal mucus. It is very thin in the meatuses on the floor of the nasal cavities, and in the various sinuses. It is one of the most commonly infected tissues in adults and children. Inflammation of this tissue may cause significant impairment of daily activities, with symptoms such as stuffy nose, headache, mouth breathing, etc.

| Nasal mucosa | |

|---|---|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica mucosa nasi, membrana mucosa nasi |

| Greek | Shaula |

| MeSH | D009297 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Owing to the thickness of the greater part of this membrane, the nasal cavities are much narrower, and the middle and inferior nasal conchæ appear larger and more prominent than in the skeleton; also the various apertures communicating with the meatuses are considerably narrowed.

Structure

The epithelium of the nasal mucosa is of two types – respiratory epithelium, and olfactory epithelium differing according to its functions. In the respiratory region it is columnar and ciliated.[3] Interspersed among the columnar cells are goblet or mucin cells, while between their bases are found smaller pyramidal cells. Beneath the epithelium and its basement membrane is a fibrous layer infiltrated with lymph corpuscles, so as to form in many parts a diffuse adenoid tissue, and under this a nearly continuous layer of small and larger glands, some mucous and some serous, the ducts of which open upon the surface. In the olfactory region the mucous membrane is yellowish in color and the epithelial cells are columnar and non-ciliated; they are of two kinds, supporting cells and olfactory cells. The supporting cells contain oval nuclei, which are situated in the deeper parts of the cells and constitute the zone of oval nuclei; the superficial part of each cell is columnar, and contains granules of yellow pigment, while its deep part is prolonged as a delicate process which ramifies and communicates with similar processes from neighboring cells, so as to form a net-work in the mucous membrane. Lying between the deep processes of the supporting cells are a number of bipolar nerve cells, the olfactory cells, each consisting of a small amount of granular protoplasm with a large spherical nucleus, and possessing two processes—a superficial one which runs between the columnar epithelial cells, and projects on the surface of the mucous membrane as a fine, hair-like process, the olfactory hair; the other or deep process runs inward, is frequently beaded, and is continued as the axon of an olfactory nerve fiber. Beneath the epithelium, and extending through the thickness of the mucous membrane, is a layer of tubular, often branched, glands, the glands of Bowman, identical in structure with serous glands. The epithelial cells of the nose, fauces and respiratory passages play an important role in the maintenance of an equable temperature, by the moisture with which they keep the surface always slightly lubricated.

— Henry Gray, Anatomy of the human body[4]

Notes

- Beule, AG (2010). "Physiology and pathophysiology of respiratory mucosa of the nose and the paranasal sinuses". GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 9: Doc07. doi:10.3205/cto000071. PMC 3199822. PMID 22073111.

- "Respiratory mucosa". mesh.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Tortora, G; Anagnostakos, N (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th Harper international ed.). Harper & Row. p. 556. ISBN 0060466693.

- Henry Gray (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body. Lea & Febiger. p. 996.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 996 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)