Nanisivik Naval Facility

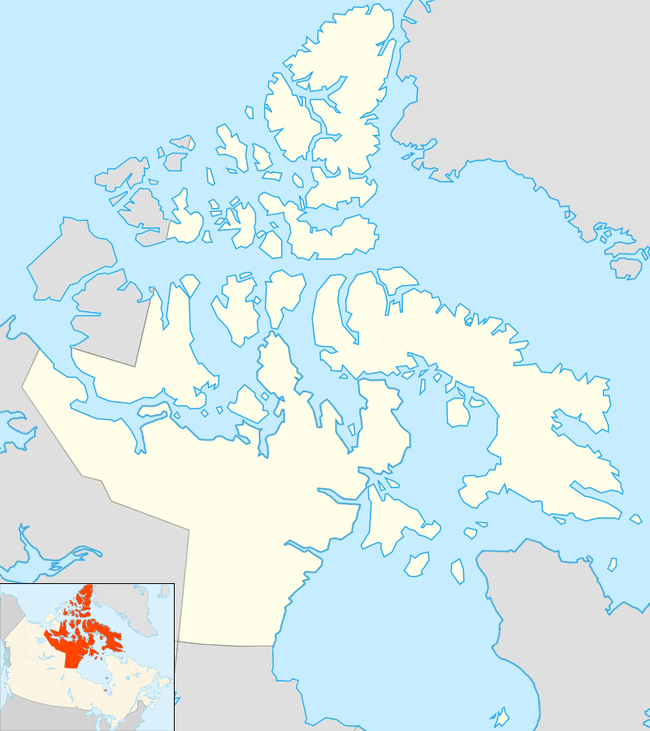

The Nanisivik Naval Facility is a Canadian Forces naval facility on Baffin Island, Nunavut. The station is built at the former lead-zinc mine site near the former company town of Nanisivik. The facility was undergoing final testing in mid-2019. Full operational capability had been expected to be achieved by mid-2020 with the first refuelling of an Royal Canadian Navy ship. However, in July 2020 it was confirmed that work on the facility would not be completed until 2022.

| Nanisivik Naval Facility | |

|---|---|

| Nanisivik, Nunavut | |

HMCS Goose Bay moored at Nanisivik. | |

Nanisivik Naval Facility  Nanisivik Naval Facility  Nanisivik Naval Facility | |

| Coordinates | 73.068889°N 84.549167°W |

| Type | Arctic Naval base |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Canadian Forces |

| Site history | |

| Built | In construction since 2015, due to finish in 2019. |

| In use | N/A |

.jpg)

.jpg)

Description

The naval station was originally planned to be home port of the Arctic offshore patrol ships that were proposed under the Harper government plan.[1][2] These ships have ice-breaking capability and help the government's goal to enforce Canada's sovereignty over the region. As well, these ships would likely allow the Victoria-class submarines to travel in the Arctic regions.

Detailed planning for the facility began in August 2007, with environmental studies and assessments to be carried out in the summer of 2008.[3] That design has since been downgraded to a docking and refuelling station. The port's operational time was also scaled back to just a four-month period in the summertime. Construction was expected to begin in 2013, with the station operational by 2016. However, construction delays continued and the opening of the port was put off until 2017 with the intent to be fully operational by 2018.[4][5]

The station will be primarily used for refuelling Arctic patrol and other government vessels. The base currently consists of storage tanks for fuelling of the new Harry DeWolf-class offshore patrol vessels, a site office, and a wharf's operator shelter. The main purpose of the base is to allow these new vessels to patrol the breadth of Canada's arctic seas during the four-month summer season.[6][7] The facility has two 3.75-million-litre (820,000 imp gal; 990,000 US gal) fuel tanks connected directly to the jetty by a pipeline. The base also has an unheated storage facility.[8]

History

The community of Nanisivik was originally built to support the Nanisivik Mine, a lead-zinc mine on Baffin Island. The mine was serviced by a jetty for receiving ocean freight, later used by the Canadian Coast Guard for training,[9] and the Nanisivik Airport, which was capable of receiving jet aircraft and closed in 2011. Falling metal prices and shrinking resources led to the mine's closure in 2002.[10]

On 8 August 2007, CBC News reported documents from the Canadian Forces showing plans to convert the site into a naval station. The plan was to turn the former mine's existing port into a deepwater facility at a cost of $60 million.[11] On 10 August 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced construction of a new docking and refuelling facility at Nanisivik for the Canadian Forces, in an effort to maintain a Canadian presence in Arctic waters during the navigable season (June–October). The choice for Nanisivik as a site was partially based on its location within the eastern entrance to the Northwest Passage, via Admiralty Inlet, and the existence of a deep-water berthing facility at the site, as well as a location of the airport. The United States Air Force's Thule Air Base is 600 km (370 mi) to the northeast in Greenland.

On 20 August 2010, the Kingston-class coastal defence vessel HMCS Goose Bay became the first Canadian warship to secure to the Nanisivik jetty as part of Operation Nanook. Two days later, the frigate HMCS Montréal secured alongside for a photo opportunity. The Coast Guard icebreaker CCGS Henry Larsen was also present, but did not go alongside at that time.

In 2011 and 2012, the government started backing down on the Nanisivik conversion plans, explaining that construction in the far north is too expensive. Total costs in 2011 were set at $175 million with an extra $12 million for the design. However, costs rose $16 million above the proposed $100 million budget by 2013.[12] Reports later surfaced that the cost of the original plan more than doubled its original estimate, coming in at $258 million. Subsequently, the Department of National Defence scaled back its plans for the facility to only operate during the summer, remove the jet-capable airstrip and reduce the infrastructure at the port to a smaller tank farm, less personnel requirements and an unheated warehouse.[13][14]

Construction

Engineering for the first of four phases of design for the facility was completed by the British Columbia office of WorleyParsons at a cost of $900,000. This phase included preliminary design work and construction requirements. Construction was originally expected to begin in 2011, and the facility was expected to be operational by 2014.[15] Nyrstar NV, a mining and metals company, began performing remediation work in late 2010 with the tanks from the old tank farm being disposed of in 2011.[16]

Initial delays were caused by the sinking of the wharf. Measurements taken in 2010 showed that the wharf had sunk about 2 m (6 ft 7 in) and causes were looked for. Drilling performed in 2011 showed a deep layer of clay below the wharf, leading engineers to believe the clay was compressing and settling the wharf. The settling was among the reasons the plan for the port was scaled back.[17]

Upon receiving approval from the Nunavut Impact Review Board in 2013, construction began in August 2014. Rock crushing and other site preparation began in 2015, with construction on the new tank farm and service roads in 2016–17. By July 2017 the roofs of the fuel tanks had been placed. Final checks on the facility were supposed to be performed during the summer months of 2018 in preparation for the base becoming operational in late 2018.[18] However, in mid-2019 it was announced that final tests were taking place.[19] In 2020 it was confirmed that the station would now not be fully operational until 2022.[20]

See also

- CCGS John G. Diefenbaker – proposed Arctic icebreaker

- CFS Alert – Canada's other arctic military installation

References

- "Nanisivik Naval Facility: Project Summary" (PDF). Department of National Defence. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- "Nanisivik Naval Facility Project: Overview Presentation to Stakeholders – 27 October 08" (PDF). Department of National Defence. 27 October 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- "Backgrounder – Expanding Canadian Forces Operations in the Arctic". Prime Minister of Canada. 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- "Arctic naval facility at Nanisivik completion delayed to 2018". CBC News. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- De Souza, Mike (2 March 2015). "Canadian navy delays opening of crucial Arctic facility to 2018". Toronto Sun. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Rogers, Sarah (6 March 2015). "Nanisivik naval fuel station postponed until 2018: National Defence". NunatsiaqOnline. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Bird, Michael (4 March 2015). "Making waves: The Navy's Arctic ambition revealed". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Frizzell, Sara (10 July 2017). "Nanisivik naval refuelling facility in Nunavut on track and on budget for fall 2018 opening". CBC News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Arcticnet – Naval gazing: Looking for a High Arctic port". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- Green, Mary Ellen (28 October 2009). "Nanisivik naval depot project on schedule". The Maple Leaf. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- "Planned army base, port in North heat up Arctic quest". CBC News. 8 August 2007. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- "Ottawa's Arctic port plan mired in delays". CBC News. The Canadian Press. 1 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Pugliese, David (8 September 2014). "Nanisivik naval facility was originally supposed to cost $258 million but DND balked at price tag". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Arctic naval facility downgrade due to high cost, says DND". CBC News. 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- "B.C. firm wins design contract for Arctic naval port". CBC News. 26 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- Dolphin, Myles (18 November 2013). "Naval facility delayed". Northern News Service Online. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Chase, Steven (27 January 2014). "Hub for Canada's Arctic patrols has got that sinking feeling". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Frizzell, Sara (10 July 2017). "Nanisivik naval refuelling facility in Nunavut on track and on budget for fall 2018 opening". CBC News. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- @@CanadianForces (16 August 2019). "We're happy to have had the HMCSVilleDeQuebec stop by our Nanisivik Naval Facility this week for dry testing!" (Tweet). Retrieved 11 August 2020 – via Twitter.

- "Canada receives first new Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ship". Mirage News. 1 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.