Name of Syria

The name Syria is latinized from the (Greek Συρία Suría). Herodotus used it loosely to refer to Cappadocia.[1] In Greek usage, Συρία Suría and Ασσυρία Assuría were used almost interchangeably, but in the Roman Empire, Syria and Assyria came to be used as distinct geographical terms. "Syria" in the Roman Empire period referred to the region of Syria (the western Levant, "those parts of the Empire situated between Asia Minor and Egypt"), while Asōristān was part of the Sasanian Empire and only very briefly came under Roman control (AD 116–118, marking the historical peak of Roman expansion).

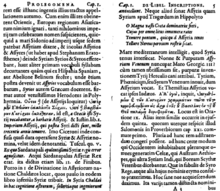

Etymologically, the name Syria is connected to Assyria, ultimately from the Akkadian Aššur. Theodor Nöldeke in 1881 was the first to give philological support to the assumption that Syria and Assyria have the same etymology,[2] a suggestion going back to John Selden (1617). Current academic opinion favours the connection.

Modern Syria (Arabic: الجمهورية العربية السورية "Syrian Arab Republic", since 1961) inherits its name from the Ottoman Syria Vilayet, established in 1865. The choice of the ancient Latin name for the Ottoman province reflects a growing historical consciousness among the local intellectuals at the time.[3] The Classical Arabic name for the region is بلاد اَلشَّأم bilād aš-ša'm ("land to the north", Modern Standard Arabic اَلشَّام aš-šām) from شأم š'm "left hand; northern".[4] In contrast, Baalshamin (Aramaic: ܒܥܠ ܫܡܝܢ, romanized: Lord of Heaven(s)),[5][6] was a Semitic sky-god in Canaan/Phoenicia and ancient Palmyra.[7][8] Hence, Sham refers to (heaven or sky).

Etymology

Majority mainstream scholarly opinion now strongly supports the already dominant position that 'Syrian' and Syriac indeed derived from 'Assyrian', and the 21st-century discovery of the Çineköy inscription seems to clearly confirm that Syria is ultimately derived from the Assyrian term Aššūrāyu.[9]

The question was addressed from the Early Classical period through to the Renaissance Era by the likes of Herodotus, Strabo, Justinus, Michael the Syrian and John Selden, with each of these stating that Syrian/Syriac was synonymous and derivative of Assyrian. Acknowledgments being made as early as the 5th century BC in the Hellenistic world that the Indo-European term Syrian was a derived from the much earlier Assyrian.

Some 19th-century historians such as Ernest Renan had dismissed the etymological identity of the two toponyms.[10] Various alternatives had been suggested, including derivation from Subartu (a term which most modern scholars in fact accept is itself an early name for Assyria, and which was located in northern Mesopotamia), the Hurrian toponym Śu-ri, or Ṣūr (the Phoenician name of Tyre). Syria is known as Ḫrw (Ḫuru, referring to the Hurrian occupants prior to the Aramaean invasion) in the Amarna Period Egypt, and as אֲרָם, ʾĂrām in Biblical Hebrew. J. A. Tvedtnes had suggested that the Greek Suria is loaned from Coptic, and due to a regular Coptic development of Ḫrw to *Šuri.[11] In this case, the name would derive directly from that of the language isolate-speaking Hurrians, and be unrelated to the name Aššur. Tvedtnes' explanation was rejected as highly unlikely by Frye in 1992.

Various theories have been advanced as to the etymological connections between the two terms. Some scholars suggest that the term Assyria included a definite article, similar to the function of the Arabic language "Al-".[12] Theodor Nöldeke in 1881 gave philological support to the assumption that Syria and Assyria have the same etymology,[13] a suggestion going back to John Selden (1617) rooted in his own Hebrew tradition about the descent of Assyrians from Jokshan. Majority and mainstream current academic opinion strongly favours that Syria originates from Assyria. A hieroglyphic Luwian and Phoenician bilingual monumental inscription found in Çineköy, Turkey, (the Çineköy inscription) belonging to Urikki, vassal king of Que (i.e. Cilicia), dating to the eighth century BC, reference is made to the relationship between his kingdom and his Assyrian overlords. The Luwian inscription reads su-ra/i whereas the Phoenician translation reads ʾšr, i.e. ašur, which according to Rollinger (2006) "settles the problem once and for all".[13]

According to a different hypothesis, the name Syria might be derived from "Sirion"[14] (Hebrew: שִׂרְיֹ֑ן Širyôn,[note 1] meaning "breastplate")[note 2][17][18], the name that the Phoenicians (especially Sidonians) gave to Mount Hermon,[19][note 3] firstly mentioned in an Ugaritic poem about Baal and Anath:

They [ ... ] from Lebanon and its trees, from [Siri]on its precious cedars.

History

The Greek name appears to correspond to Phoenician ʾšr "Assur", ʾšrym "Assyrians", recorded in the 8th-century BC Çineköy inscription.[13]

Writing in the 5th century BC, Herodotus stated that those called Syrians by the Greeks were called Assyrians by themselves and in the East.[22] [9] In Greek usage, Syria and Assyria were used almost interchangeably in reference to Assyria, although Herodotus distinguished between the names Syria and Assyria, and for him, Syrians are the inhabitants of the Levant. Randolph Helm emphasised that Herodotus never applied the term Syria on the Mesopotamian region of Assyria which he always called "Assyria".[23]

In the Roman Empire, Syria and Assyria came to be used as distinct geographical terms. "Syria" in the Roman Empire period referred to those parts of the Empire situated between Asia Minor and Egypt, i.e. the western Levant, while "Assyria" in northern Iraq, southeast Turkey and northeast Syria was part of the Persian Empire as Athura, and only very briefly came under Roman control (116–118 AD, marking the historical peak of Roman expansion), where it was known as Assyria Provincia.

In 1864, the Ottoman Vilayet Law was promulgated to form the Syria Vilayet.[24] The new provincial law was implemented in Damascus in 1865, and the reformed province was named Suriyya/Suriye, reflecting a growing historical consciousness among the local intellectuals.[24]

See also

- Names of the Levant

- Syria (region)

- Greater Syria

- Names of Syriac Christians

- Çineköy inscription

- Name of India

Notes

- The Semitic trilateral root of the word might be (Hebrew: שָׂרָה), meaning to "persist" or "persevere".[15]

- Later on, Christian Arameans used the term "Syriacs" in order to distinguish themselves from pagan Arameans.[16]

- The Hebrews called the mountain "Hermon", while the Amorites referred to it as "Šeni'r".[20]

References

- Hdt. VII.63. Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.63".

VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

- The Origin of the Terms ‘Syria(n)’ and Suryoyo: Once Again, Johny Messo

- The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516-1918: A Social and Cultural History, pp. 177, 181-182. Bruce Masters, Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- The Levant as "the northern region" (as seen from Arabia), from the convention of east-oriented maps. Lane, Arabic Lexicon (1863) I.1400.

- Teixidor, Javier (2015). The Pagan God: Popular Religion in the Greco-Roman Near East. Princeton University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781400871391. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001). The Rough Guide to Syria. Rough Guides. p. 290. ISBN 9781858287188. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Dirven, Lucinda (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. BRILL. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-04-11589-7. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- J.F. Healey (2001). The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. BRILL. p. 126. ISBN 9789004301481. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Frye, R. N. (October 1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570.

- "Syria is not but a contraction of Assyria or Assyrian; this according to the Greek pronunciation. The Greeks applied this name to all of Asia Minor." cited after Sa Grandeur Mgr. David, Archevêque Syrien De Damas, Grammair De La Langue Araméenne Selon Les Deux Dialects Syriaque Et Chaldaique Vol. 1,, (Imprimerie Des Péres Dominicains, Mossoul, 1896), 12.

- Tvedtnes, John A. (1981). "The Origin of the Name "Syria"". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 40 (2): 139. doi:10.1086/372868.

- A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and Geography, Sir William Smith, Charles Anthon, Harper & Brothers, 1862 "Even when the name of Syria is used in its ordinary narrower sense, it is often confounded with Assyria, which only differs from Syria by having the definite article prefixed."

- Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- Nissim Raphael Ganor (2009). Who Were the Phoenicians?. Kotarim International Publishing. p. 252. ISBN 9659141521.

- 8280. sarah, biblehub.com

- Christoph Luxenberg (2007). The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran. Hans Schiler. p. 9. ISBN 9783899300888.

- "Sirion". Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- "Hebrew: שִׁרְיוֹן, širyôn (H8303)". Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Pipes, Daniel (1992). Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition. Middle East Forum. p. 13. ISBN 0-19-506022-9. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- Sir William Smith (1863). A Dictionary of the Bible: Red-Sea-Zuzims. Princeton University. p. 1195.

- James B. Pritchard, Daniel E. Fleming (2010). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0691147264.

- (Pipes 1992), s:History of Herodotus/Book 7

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.63".VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.72".VII.72: In the same fashion were equipped the Ligyans, the Matienians, the Mariandynians, and the Syrians (or Cappadocians, as they are called by the Persians).

Missing or empty|url=(help) - John Joseph (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. p. 21. ISBN 9004116419.

- The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516–1918: A Social and Cultural History, pp. 177, 181-182. Bruce Masters, Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-107-03363-4

Bibliography

- Assyrians, Syrians and the Greek Language in the late Hellenistic and Roman Imperial Periods, Nathanael Andrade, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 73, No. 2, October 2014, DOI: 10.1086/677249, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/677249

- Joseph, John (2008). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?" (PDF).

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (25 July 2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-24456-6.