Nakula Sahadeva Ratha

Nakula Sahadeva Ratha is a monument in the Pancha Rathas complex at Mahabalipuram, on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal, in the Kancheepuram district of the state of Tamil Nadu, India. It is an example of monolith Indian rock-cut architecture. Dating from the late 7th century, it is attributed to the reign of King Mahendravarman I and his son Narasimhavarman I (630–680 AD; also called Mamalla, or "great warrior") of the Pallava Kingdom. The entire complex is under the auspices of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and is one of the Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram that were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984.[1]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Nakula and Sahadeva Ratha | |

| Location | Mamallapuram, Kanchipuram district, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Part of | Main complex of Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii), (vi) |

| Reference | 249-001 |

| Inscription | 1984 (8th session) |

| Coordinates | 12°37′03″N 80°11′56″E |

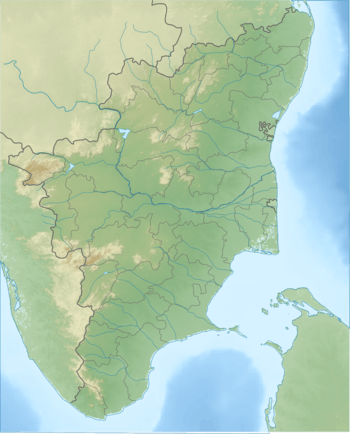

Location of Nakula Sahadeva Ratha in Tamil Nadu  Nakula Sahadeva Ratha (India) | |

Resembling a chariot (ratha), it is carved out of a single, long stone of pink granite.[1][2][3] Though sometimes mistakenly referred to as a temple, the structure was not consecrated because it was not completed[4] following the death of Narasimhavarman I.[2][3][5] The structure is named after the last two brothers of the Pancha Pandavas, of epic Mahabharata fame,[1][3][6] though the nomenclature is not supported by history.[7] The small unfinished structure is dedicated to the god Indra.

Geography

The structure is located at Mahabalipuram (previously known as Mammallapuram) on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal of the Indian Ocean in Kancheepuram district. It is approximately 35 miles (56 km) south of Chennai (previously known as Madras), the capital city,[8] while Chengalpattu is about 20 miles (32 km) distant.[9]

The ratha complex is situated close to the shore line. Though the Nakula Sahadeva ratha is part of the Pancha Rathas, it is situated separate from the other four rathas. The Nakula-Sahadeva faces south, while the Dharmaraja, Bhima, Arjuna and Draupadi Rathas face west.[5][10][11] The view from outside the ratha has similarity with the Chaitya Hall of a Buddhist temple, though on a small scale.[12]

Etymology

Though it is considered to be a monolith temple, "temple" is misnomer given that the five rathas were never completed,[13] as evidenced by uncarved bed rock at the pinnacle. Hence, the rathas were neither consecrated nor worship offered. The structure is named after the twins, Nakula and Sahadeva, the last two born of the five Pandava brothers of the epic Mahabharata fame.[14] Nakula Sahadeva is also referred to as "Gajaprishtakara",[15] a Sanskrit technical name for the backside of an elephant.[16]

History

The feature of this ratha and the other four cannot be definitely dated to any other similar constructions in the past in any ancient Indian architecture. However, the five rathas have been forerunners or templates for the development of Indian temple architecture. Like the other four Pancha Rathas, this stone edifice is a replica of a wooden version which preceded it.[17] Though it is considered to be a monolith temple, "temple" is a misnomer given that the five rathas were never completed,[13] as evidenced by uncarved bedrock at the pinnacle. Hence, the rathas were neither consecrated nor worship offered. The incomplete status of all the five rathas is attributed to the death of the king Narasimhavarman I in 668 AD.[6][18] Even the epic name associated with the Pandavas is not supported by history. Along with several other monuments, this ratha gained UNESCO World Heritage Site distinction in 1984 as "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram".[1]

Architecture

All the Pancha Rathas are aligned in a north-south direction and share a common plinth. They have no precedent in Indian architecture and have proved to be "templates" for building larger temples in the South Indian tradition of Dravidian temple architecture.[6] Though cut out of monolithic rocks, they are carved in the form of structural temples in regular building form and hence termed as "quasimonolithic temple form".

Layout

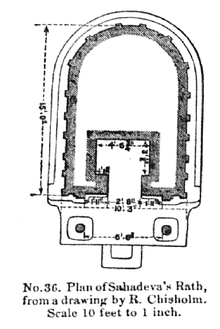

Viewed from the entrance gate, which is facing west, it is in curved shape, and appears like the backside of an elephant and hence the style is termed gajapristha (back of an elephant). To add to this epithet, a large sized elephant sculpture, a monolithic sculpture, is carved next to the ratha.[14][18][19] The ratha is classified under the vasara style.[20] This monolithic structure, along with the other Pancha Rathas, opposite to the Arjuna Ratha, was built out of a single rock outcrop of granite. It is an apsidal (horseshoe-shaped) dvitala (two tiered) free standing structure, entirely of Dravidian architecture. It is built on the same base, at the end of the three rathas of Dharmaraja, Bhima and Arjuna, but facing south. There are no idols to worship inside the ratha. The walls of this ratha also have features arranged in a sequence to delineate the "projections and recesses created by pairs of shallow pilasters." The niches on the interior walls of the ratha have carved images of gods and demi-gods. The roof (in the form of the back of an elephant) terminates as a pyramid or finial or shikara, which is carved with motifs. The unusual architecture of this ratha is said to be an innovation of the architect.[19]

Features

The ratha with its simple layout has least embellishments. The apses on the front facade, which is also the mukha-mandapa (entrance porch) of the ratha has no decorations and the façade is supported on two pillars mounted on lion-base. The chamber inside is flanked by two pilasters with elephant carvings depicted as the guardians. The cornice, all along the shrine, is supported on pillars with corbels and embellished with kudus (horseshoe-shaped dormer windows) with images of human head inside.[18]

The carvings were sculpted from the top to the bottom of rathas.[21] The sculpture in the form of reliefs on the walls inside the ratha is of Ardhanariswara.[22] It is also mentioned that this ratha is dedicated to Candesa, and the elephant sculpture placed outside the ratha is considered an unusual location, as a Vahana or a mount of god, while it is normally placed in front of the ratha).[23] In the two storeys above the ground floors (above the cornices) oblong gabled shrines and square corner shrines are seen which are interlinked by a cloister all around the edge. On the west side, which is gabled, carvings seen are of three gates. In the central door the shrine sculpted with a square tower has a finial on top. The uppermost floor is apsidal and has a large kudu with a shrine inside.[18]

References

- "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- "File:Five Rathas, Mahabalipuram.jpg". Archarological Survey of India, Chennai Circle. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- "Pancha Rathas, Mamallapuram". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Marilyn Stokstad (2008). Art history. Pearson Education. p. 333. ISBN 9780131577046.

- "Mahabalipuram". UCLA Education, South Asia. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "The Rathas, monolithic [Mamallapuram]". Online Gallery of the British Library. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- File:Infoboard board of Pancha Rathas.jpg

- Gunther, Michael D. "Pancha Rathas, Mamallapuram". art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Ayyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. Asian Educational Services. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-81-206-0151-2. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-90-04-06498-0. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "A monumental effort". Front Line India's National Magazine from the publishers of The Hindu. 8 November 2003. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Subramanian, K. R. (1 January 1996). Buddhist Remains in Āndhra and the History of Āndhra Between 225 & 610 A.D. Asian Educational Services. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-81-206-0444-5. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Stokstad, Marilyn (2008). Art history. Pearson Education. p. 333. ISBN 9780131577046.

- Schreitmüller, Karen; Dhamotharan, Mohan; Szerelmy, Beate (14 February 2012). India Baedeker Guide. Baedeker. pp. 589–. ISBN 978-3-8297-6622-7. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Singh, Sarina (1 September 2009). India 13. Lonely Planet. pp. 1060–. ISBN 978-1-74179-151-8. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Abram, David; Edwards, Nick (1 February 2004). Rough Guide to South India 3. Rough Guides. pp. 447–. ISBN 978-1-84353-103-6. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Moffett, Marian; Fazio, Michael W.; Wodehouse, Lawrence (2003). World History of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-85669-371-4. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- "Mahabalipuram – The Workshop of Pallavas – Part III". 6. Ganesha Ratha. Indian History and Architecture, Puratattva.in. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "World Heritage Sites – Mahabalipuram: Group of Monuments Mahabalipuram (1984), Tamil Nadu". Archaeological Survey of India by National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Rajan, K. V. Soundara (1978). The art of south India: Tamil Nadu & Kerala. Sundeep Prakashan. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Gupta, Shobhna (2003). Monuments Of India. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-81-241-0926-7. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "Pancha Rathas, Mahabalipuram". Wonder Mondo.com. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-90-04-06498-0. Retrieved 3 January 2013.