Dharmaraja Ratha

Dharmaraja Ratha is a monument in the Pancha Rathas complex at Mahabalipuram, on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal, in the Kancheepuram district of the state of Tamil Nadu, India. It is an example of monolith Indian rock-cut architecture. Dating from the late 7th century, it is attributed to the reign of King Mahendravarman I and his son Narasimhavarman I (630–680 AD; also called Mamalla, or "great warrior") of the Pallava Kingdom. The entire complex is under the auspices of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). It is one of the Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram that were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984.[3]

| Dharmaraja Ratha | |

|---|---|

Dharmaraja Ratha | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| District | Kancheepuram district |

| Deity | Shiva |

| Location | |

| Location | Mahabalipuram |

| State | Tamil Nadu, |

| Country | India |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | c. 650[1] Common era[2] |

Resembling a chariot (ratha), it is carved out of a single, long stone of pink granite.[3][4][5] Though sometimes mistakenly referred to as a temple, the structure was not consecrated because it was not completed[6] following the death of Narasimhavarman I.[4][5][7] The structure is named after the eldest of the Pancha Pandavas, of epic Mahabharata fame,[3][5][8] though this nomenclature is not supported by its iconography.[4] It is dedicated to Shiva.[9]

Geography

The structure is located at Mahabalipuram (previously known as Mammallapuram) on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal in Kancheepuram district. It is approximately 35 miles (56 km) south of Chennai (previously known as Madras), the capital city,[10] while Chengalpattu is about 20 miles (32 km) away.[11]

History

Like the other four Pancha Rathas, Dharmaraja ratha was built from stone, a replica of a wooden version which preceded it.[12] The temple is incomplete.[8]

Architecture

All the Pancha Rathas are aligned in a north-south direction and share a common plinth. They have no precedent in Indian architecture and have proved to be "templates" for building larger temples in the South Indian tradition of Dravidian temple architecture.[8] Though cut out of monolithic rocks, they are carved in the form of structural temples in regular building form and hence termed as "quasimonolithic temple form.

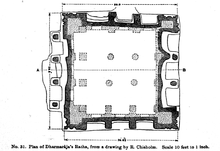

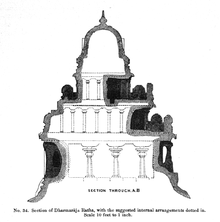

Dharmaraja Ratha is the most prominent architecturally of the five rathas and also the tallest and largest.[13][14][15] The ratha faces west and is sculpturally very rich. It has three floors including the ground floor. The plan of the ground floor measure a square of 28 feet (8.5 m) and has a height of 35 feet (11 m) from ground level to the top of the roof. It is open on all four sides and the facade on all sides are supported by two pillars and two pilasters with the corners forming an integral part of the support system for the upper floors. Carved out from a single rock of pink granite,[16][17] along with other three rathas on a single block of stone oriented in a north-south direction,[5] it is a trithala or three-story[18][19] vimana,[20] square in plan, with open porches and a terraced pyramidal tower.[21] and an octagonal shikhara (pinnacle) at the top. Small-sized model shrines called kudus make up the ornament of the upper part of the tower.[9][22] There are many sculptures on the corners of the sanctum, which depict Shiva;[23] Harihara, Brahma-Sasta, Skanda, Brahma, Ardhanarisvara (half Shiva half Parvati)[24] and Krishna[25] are depicted alongside an inscribed portrait of a king, indicated to be Narasimhavarman I,[21][26][27] who commissioned the temple.[28] The shafts of the pillars are supported by seated lions.[21] The second floor contains rich imagery,[29] with further depictions of Shiva as Gangadara and Natesa, and Vishnu resting on Garuda and Kaliya Mardhana.

Inscriptions

On the Dharmaraja Rathas there are 16 inscriptions in Grantha and Nagari scripts in Sanskrit inscriptions on which are royal cognomen, single-word titles, most of them are attributed to Narasimhavarman I.[30] On the top tier of the temple is an inscription which refers to it as Atyantakama Pallavesvaram; Atyantakama was one of the known titles of Paramesvaravarman I. Other inscribed titles for the king are Shri Megha and Trailokiya–vardhana-vidhi.[26]

References

- The Culture of India. The Rosen Publishing Group. 2010. p. 315. ISBN 9780852297629.

- Indu Ramchandani (2000). Student Britannica India 7 Vols. Popular Prakashan. p. 5. ISBN 9780852297629.

- "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- "File:Five Rathas, Mahabalipuram.jpg". Archarological Survey of India, Chennai Circle. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- "Pancha Rathas, Mamallapuram". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Marilyn Stokstad (2008). Art history. Pearson Education. p. 333. ISBN 9780131577046.

- "Mahabalipuram". UCLA Education, South Asia. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "The Rathas, monolithic [Mamallapuram]". Online Gallery of Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- Margaret Prosser Allen (1991). Ornament in Indian Arch. p. 139.

- Michael D. Gunther. "Pancha Rathas, Mamallapuram". art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- P. V. Jagadisa Ayyar (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. Asian Educational Services. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-81-206-0151-2. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Moffett, Marian; Fazio, Michael W.; Wodehouse, Lawrence (2003). World History of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-85669-371-4. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Rina Kamath (2000). Chennai. Orient Blackswan. p. 121.

- History & Civics IX. Rachnar Sagnar. p. 127.

- K. V. Soundara Rajan (2002). Concise Classified Dictionary of Hinduism. Concept Publishing. p. 260.

- Indian Railways. 15. India Railway Board. 1970.

- Our Story So Far. 6. Pearson Education India. p. 102. ISBN 9788131714942.

- Aline Dobbie (2006). India: The Elephant's Blessing. Melrose Press. p. 56. ISBN 9781905226856.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. p. 279. ISBN 9780143415176.

- D. Dennis Hudson (2008). The Body of God: An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram. Oxford University Press. p. 537. ISBN 9780195369229.

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 636. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Hugh Honour; John Fleming (2005). A World History of Art.

- Roshen Dalal (2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 294. ISBN 9780143414216.

- Karen Schreitmüller; Mohan Dhamotharan; Beate Szerelmy (2012). India Baedeker Guide. p. 589.

- T. Padmaja (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Abhinav Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 9788170173984.

- "World Heritage Sites – Mahabalipuram – Monolithic Temples". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- K. R. Srinivasan (1975). The Dharmarāja ratha & its sculptures, Mahābalipuram. Abhinav Publications.

- G. Jouveau-Dubreuil (1994). Pallava Antiquities – 2 Vols. Asian Educational Services. p. 63. ISBN 9788120605718.

- Elisabeth Beck (2006). Pallava rock architecture and sculpture. Sri Aurobindo Institute of Research in Social Sciences in association with East West Books (Madras). p. 226. ISBN 9788188661466.

- "A monumental effort". Front Line India's National Magazine from the publishers of The Hindu. 8 November 2003. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.