Mustang

The mustang is a free-roaming horse of the Western United States, descended from horses brought to the Americas by the Spanish. Mustangs are often referred to as wild horses, but because they are descended from once-domesticated horses, they are actually feral horses. The original mustangs were Colonial Spanish horses, but many other breeds and types of horses contributed to the modern mustang, now resulting in varying phenotypes. Some free-roaming horses are relatively unchanged from the original Spanish stock, most strongly represented in the most isolated populations.

Mustang adopted from the BLM | |

Free-roaming mustangs | |

| Country of origin | North America |

|---|---|

| Traits | |

| Distinguishing features | Small, compact, good bone, very hardy |

In 1971, the United States Congress recognized that "wild free-roaming horses and burros are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West, which continue to contribute to the diversity of life forms within the Nation and enrich the lives of the American people".[1] The free-roaming horse population is managed and protected by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Controversy surrounds the sharing of land and resources by mustangs with the livestock of the ranching industry, and also with the methods by which the BLM manages their population numbers. The most common method of population management used is rounding up excess population and offering them to adoption by private individuals. There are inadequate numbers of adopters, so many once free-roaming horses now live in temporary and long-term holding areas with concerns that the animals may be sold for horse meat. Additional debate centers on the question of whether mustangs—and horses in general—are a native species or an introduced invasive species in the lands they inhabit.

Etymology and usage

Although free-roaming Mustangs are called "wild" horses, they descend from feral domesticated horses.[lower-alpha 1]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the English word mustang was likely borrowed from two essentially synonymous Spanish words, mestengo (or mesteño) and mostrenco.[4] English lexicographer John Minsheu glossed both words together as 'strayer' in his dictionary of 1599.[4] Both words referred to livestock defined as 'wild, having no master'.[lower-alpha 2] Mostrenco was used since the 13th century, while mestengo is attested from the late 15th.[4]

Mesteño referred originally to beasts of uncertain ownership distributed by the powerful transhumant merino sheep ranchers' guild in medieval Spain, called the Mesta (Honrado Concejo de la Mesta, 'Honorable Council of the Mesta').[6][7][4] The name of the Mesta derived ultimately from the Latin: mixta, lit. 'mixed', referring to the common ownership of the guild's animals by multiple parties.[7] The OED states that the origin of mostrenco is "obscure" but notes the Portuguese: mostrengo is attested from the 15th century.[4] In Spanish, mustangs are named mesteños. By 1936, the English 'mustang' had been loaned back into Spanish as mustango.[4]

"Mustangers" (Spanish: mesteñeros) were cowboys (vaqueros) who caught, broke, and drove free-ranging horses to market in the Spanish and later American territories of what is now northern Mexico, Texas, New Mexico, and California. They caught the horses that roamed the Great Plains, the San Joaquin Valley of California, and later the Great Basin, from the 18th century to the early 20th century.[8][9]

Characteristics and ancestry

The original mustangs were Colonial Spanish horses, but many other breeds and types of horses contributed to the modern mustang, resulting in varying phenotypes. Mustangs of all body types are described as surefooted and having good endurance. They may be of any coat color.[10] Throughout all the Herd Management Areas managed by the Bureau of Land Management, light riding horse type predominates, though a few horses with draft horse characteristics also exist, mostly kept separate from other mustangs and confined to specific areas.[11] Some herds show the signs of the introduction of Thoroughbred or other light racehorse-types into herds, a process that also led in part to the creation of the American Quarter Horse.[12]

The mustang of the modern west has several different breeding populations today which are genetically isolated from one another and thus have distinct traits traceable to particular herds. Genetic contributions to today's free-roaming mustang herds include assorted ranch horses that escaped to or were turned out on the public lands, and stray horses used by the United States Cavalry.[lower-alpha 3] For example, in Idaho some Herd Management Areas (HMA) contain animals with known descent from Thoroughbred and Quarter Horse stallions turned out with feral herds.[15] The herds located in two HMAs in central Nevada produce Curly Horses.[16][17] Others, such as certain bands in Wyoming, have characteristics consistent with gaited horse breeds.[18]

Many herds were analyzed for Spanish blood group polymorphism (commonly known as "blood markers") and microsatellite DNA loci.[19] Blood marker analysis verified a few to have significant Spanish ancestry, namely the Cerbat mustang, Pryor Mountain mustang, and some horses from the Sulphur Springs HMA.[20] The Kiger mustang is also said to have been found to have Spanish blood[11] and subsequent microsatellite DNA confirmed the Spanish ancestry of the Pryor Mountain mustang.[21]

Horses in several other HMAs exhibit Spanish horse traits, such as dun coloration and primitive markings.[lower-alpha 4] Genetic studies of other herds show various blends of Spanish, gaited horse, draft horse, and pony influences.[26]

Height varies across the west; however, most are small, generally 14 to 15 hands (56 to 60 inches, 142 to 152 cm), and not taller than 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm), even in herds with draft or Thoroughbred ancestry.[lower-alpha 5] Some breeders of domestic horses consider the mustang herds of the west to be inbred and of inferior quality. However, supporters of the mustang argue that the animals are merely small due to their harsh living conditions and that natural selection has eliminated many traits that lead to weakness or inferiority.

The now-defunct American Mustang Association developed a breed standard for those mustangs that carry morphological traits associated with the early Spanish horses. These include a well-proportioned body with a clean, refined head with wide forehead and small muzzle. The facial profile may be straight or slightly convex. Withers are moderate in height, and the shoulder is to be "long and sloping". The standard considers a very short back, deep girth and muscular coupling over the loins as desirable. The croup is rounded, neither too flat nor goose-rumped. The tail is low-set. The legs are to be straight and sound. Hooves are round and dense.[10] Dun color dilution and primitive markings are particularly common among horses of Spanish type.[27]

History

1493–1600

Modern horses were first brought to the Americas with the conquistadors, beginning with Columbus, who imported horses from Spain to the West Indies on his second voyage in 1493.[29] Horses came to the mainland with the arrival of Cortés in 1519.[30] By 1525, Cortés had imported enough horses to create a nucleus of horse-breeding in Mexico.[31]

One hypothesis held that horse populations north of Mexico originated in the mid-1500s with the expeditions of Narváez, de Soto or Coronado, but it has been refuted.[32][33] Horse breeding in sufficient numbers to establish a self-sustaining population developed in what today is the southwestern United States starting in 1598 when Juan de Oñate founded Santa Fe de Nuevo México. From 75 horses in his original expedition, he expanded his herd to 800, and from there the horse population increased rapidly.[33]

While the Spanish also brought horses to Florida in the 16th century,[35] the Choctaw and Chickasaw horses of what is now the southeastern United States are believed to be descended from western mustangs that moved east, and thus Spanish horses in Florida did not influence the mustang.[33]

17th- and 18th-century dispersal

Native American people readily integrated use of the horse into their cultures. They quickly adopted the horse as a primary means of transportation. Horses replaced the dog as a pack animal and changed Native cultures in terms of warfare, trade, and even diet—the ability to run down bison allowed some people to abandon agriculture for hunting from horseback.[36]

Santa Fe became a major trading center in the 1600s.[37] Although Spanish laws prohibited Native Americans from riding horses, the Spanish used Native people as servants, and some were tasked to care for livestock, thus learning horse-handling skills.[34] Oñate's colonists also lost many of their horses.[38] Some wandered off because the Spanish generally did not keep them in fenced enclosures,[39] and Native people in the area captured some of these estrays.[40] Other horses were traded by Oñate' settlers for food, women or other goods.[33] Initially, horses obtained by Native people were simply eaten, along with any cattle that were captured or stolen.[41] But as individuals with horse-handling skills fled Spanish control, sometimes with a few trained horses, the local tribes began using horses for riding and as pack animals. By 1659, settlements reported being raided for horses, and in the 1660s the "Apache"[lower-alpha 6] were trading human captives for horses.[42] The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 also resulted in large numbers of horses coming into the hands of Native people, the largest one-time influx in history.[40]

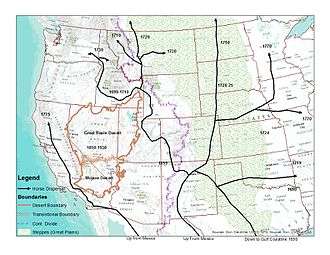

From the Pueblo people, horses were traded to the Apache, Navajo and Utes. The Comanche acquired horses and provided them to the Shoshone.[43] The Eastern Shoshone and Southern Utes became traders who distributed horses and horse culture from New Mexico to the northern plains.[44] West of the Continental Divide, horses distribution moved north quite rapidly along the western slopes of the Rocky Mountains, skirting desert regions[37] such as the Great Basin and the western Colorado Plateau.[44][lower-alpha 7] Horses reached what today is southern Idaho by 1690.[34] The Northern Shoshone people in the Snake River valley had horses in 1700.[45][lower-alpha 8] By 1730, they reached the Columbia Basin and were east of the Continental divide in the northern Great Plains.[34] The Blackfeet people of Alberta had horses by 1750.[46] The Nez Perce people in particular became master horse breeders, and developed one of the first distinctly American breeds, the Appaloosa. Most other tribes did not practice extensive amounts of selective breeding, though they sought out desirable horses through acquisition and quickly culled those with undesirable traits. By 1769, most Plain Indians had horses.[45][47]

In this period, Spanish missions were also a source of stray and stolen livestock, particularly in what today is Texas and California.[48] The Spanish brought horses to California for use at their missions and ranches, where permanent settlements were established in 1769.[47] Horse numbers grew rapidly, with a population of 24,000 horses reported by 1800.[49] By 1805, there were so many horses in California that people began to simply kill unwanted animals to reduce overpopulation.[50] However, due to the barriers presented by mountain ranges and deserts, the California population did not significantly influence horse numbers elsewhere at the time.[47][lower-alpha 9] Horses in California were described as being of "exceptional quality".[50]

In the upper Mississippi basin and Great Lakes regions, the French were another source of horses. Although horse trading with native people was prohibited, there were individuals willing to indulge in illegal dealing, and as early as 1675, the Illinois people had horses. Animals identified as "Canadian", "French", or "Norman" were located in the Great Lakes region, with a 1782 census at Fort Detroit listing over 1000 animals.[52] By 1770, Spanish horses were found in that area,[34] and there was a clear zone from Ontario and Saskatchewan to St. Louis where Canadian-type horses, particularly the smaller varieties, crossbred with mustangs of Spanish ancestry. French-Canadian horses were also allowed to roam freely, and moved west, particularly influencing horse herds in the northern plains and inland northwest.[52]

Although horses were brought from Mexico to Texas as early as 1542, a stable population did not exist until 1686, when Alonso de León's expedition arrived with 700 horses. From there, later groups brought up thousands more, deliberately leaving some horses and cattle to fend for themselves at various locations, while others strayed.[53] By 1787, these animals had multiplied to the point that a roundup gathered nearly 8,000 "free-roaming mustangs and cattle".[54] West-central Texas, between the Rio Grande and Palo Duro Canyon, was said to have the most concentrated population of feral horses in the Americas.[46] Throughout the west, horses escaped human control and formed feral herds, and by the late 1700s, the largest numbers were found in what today are the states of Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and New Mexico.[46]

19th century

An early 19th-century reference to mustangs by American sources came from Zebulon Pike, who in 1808 noted passing herds of "mustangs or wild horses". In 1821, Stephen Austin noted in his journal that he had seen about 150 mustangs.[55][lower-alpha 10]

Estimates of when the peak population of mustangs occurred and total numbers vary widely between sources. No comprehensive census of feral horse numbers was ever performed until the time of the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 and any earlier estimates, particularly prior to the 20th century, are speculative.[56] Some sources simply state that "millions" of mustangs once roamed western North America.[57][58] In 1959, geographer Tom L. McKnight[lower-alpha 11] suggested that the population peaked in the late 1700s or early 1800s, and the "best guesses apparently lie between two and five million".[46] Historian J. Frank Dobie hypothesized that the population peaked around the end of the Mexican–American War in 1848, stating: "My own guess is that at no time were there more than a million mustangs in Texas and no more than a million others scattered over the remainder of the West."[60] J. Edward de Steiguer[lower-alpha 12] questioned Dobie's lower guess as still being too high.[62]

In 1839, the numbers of mustangs in Texas had been augmented by animals abandoned by Mexican settlers who had been ordered to leave the Nueces Strip.[63][64][lower-alpha 13] Ulysses Grant, in his memoir, recalled seeing in 1846 an immense herd between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande in Texas: "As far as the eye could reach to our right, the herd extended. To the left, it extended equally. There was no estimating the number of animals in it; I have no idea that they could all have been corralled in the state of Rhode Island, or Delaware, at one time."[66] When the area was ceded to the U.S. in 1848, these horses and others in the surrounding areas were rounded up and trailed north and east,[67] resulting in the near-elimination of mustangs in that area by 1860.[65]

Farther west, the first known sighting of a free-roaming horse in the Great Basin was by John Bidwell near the Humboldt Sinks in 1841. Although John Charles Fremont noted thousands of horses in California,[68] the only horse sign he spoke of in the Great Basin, which he named, was tracks around Pyramid Lake, and the natives he encountered there were horseless.[69][lower-alpha 14] In 1861, another party saw seven free-roaming horses near the Stillwater Range.[71] For the most part, free-roaming horse herds in the interior of Nevada were established in the latter part of the 1800s from escaped settlers' horses.[68][72][73]

20th century

In the early 1900s, thousands of free-roaming horses were rounded up for use in the Spanish–American War[74] and World War I.[75]

By 1920, Bob Brislawn, who worked as a packer for the U.S. government, recognized that the original mustangs were disappearing, and made efforts to preserve them, ultimately establishing the Spanish Mustang Registry.[76] In 1934, J. Frank Dobie stated that there were just "a few wild [feral] horses in Nevada, Wyoming and other Western states" and that "only a trace of Spanish blood is left in most of them"[77] remaining. Other sources agree that by that time, only "pockets" of mustangs that retained Colonial Spanish Horse type remained.[78]

By 1930, the vast majority of free-roaming horses were found west of Continental Divide, with an estimated population between 50,000–150,000.[79] They were almost completely confined to the remaining General Land Office (GLO)-administered public lands and National Forest rangelands in the 11 Western States.[80] In 1934, the Taylor Grazing Act established the United States Grazing Service to manage livestock grazing on public lands, and in 1946, the GLO was combined with the Grazing Service to form the Bureau of Land Management (BLM),[81] which, along with the Forest Service, was committed to removing feral horses from the lands they administered.

By the 1950s, the mustang population dropped to an estimated 25,000 horses.[82] Abuses linked to certain capture methods, including hunting from airplanes and poisoning water holes, led to the first federal free-roaming horse protection law in 1959.[83] This statute, titled "Use of aircraft or motor vehicles to hunt certain wild horses or burros; pollution of watering holes"[84] popularly known as the "Wild Horse Annie Act", prohibited the use of motor vehicles for capturing free-roaming horses and burros.[85] Protection was increased further by the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 (WFRHABA).[86]

The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 provided for protection of certain previously established herds of horses and burros. It mandated the BLM to oversee the protection and management of free-roaming herds on lands it administered, and gave U.S. Forest Service similar authority on National Forest lands.[56] A few free-ranging horses are also managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service,[87] and National Park Service.[88] and the National Park Service.[88] but for the most part they are not subject to management under the Act.[89] A census completed in conjunction with passage of the Act found that there were approximately 17,300 horses (25,300 combined population of horses and burros) on the BLM-administered lands and 2,039 on National Forests.[90]

Mustangs today

The BLM has established Herd Management Areas to determine where horses will be sustained as free-roaming populations.[91] The BLM has established "Appropriate Management Levels" (AML) for each HMA, totaling 26,000 bureau-wide,[92][93] but the on-range mustang population in August 2017 was estimated to be over 72,000 horses.[94] More than half of all free-roaming mustangs in North America are found in Nevada (which features the horses on its State Quarter), with other significant populations in California, Oregon, Utah, Montana, and Wyoming.[95][lower-alpha 15] Another 45,000 horses are in holding facilities.[94]

Land use controversies

Prehistoric context

The horse, clade Equidae, originated in North America 55 million years ago.[96] By the end of the Late Pleistocene, there were two lineages of the equine family known to exist in North America: the "caballine" or "stout-legged horse" belonging to the genus Equus, and Haringtonhippus francisci, the "stilt-legged horse".[97][98] Recent studies of ancient DNA suggest that the North American caballine horses included the ancestor of the modern horse.[99][98][100] At the end of the Last Glacial Period, the non-caballines went extinct and the caballines were extirpated from the Americas. Multiple factors that included changing climate and the impact of newly arrived human hunters may have been to blame.[101] Thus, prior to the Columbian Exchange, the youngest physical evidence (macrofossils-generally bones or teeth) for the survival of Equids in the Americas dates between ≈10,500 and 7,600 years before present.[102]

Modern issues

Due in part to the prehistory of the horse, there is controversy as to the role mustangs have in the ecosystem as well as their rank in the prioritized use of public lands, particularly in relation to livestock. There are multiple viewpoints. Some supporters of mustangs on public lands asserts that, while not native, mustangs are a "culturally significant" part of the American West, and acknowledge some form of population control is needed.[103] Another viewpoint is that mustangs reinhabited an ecological niche vacated when horses went extinct in North America,[104] with a variant characterization that horses are a reintroduced native species that should be legally classified as "wild" rather than "feral" and managed as wildlife. The "native species" argument centers on the premise that the horses extirpated in the Americas 10,000 years ago are closely related to the modern horse as was reintroduced.[105][106] Thus, this debate centers in part around the question of whether horses developed an ecomorphotype adapted to the ecosystem as it changed in the intervening 10,000 years.[103]

The Wildlife Society views mustangs as an introduced species stating: "Since native North American horses went extinct, the western United States has become more arid ... notably changing the ecosystem and ecological roles horses and burros play." and that they draw resources and attention away from true native species.[107] A 2013 report by the National Research Council of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine also challenged the idea of horses being a reintroduced native species stating that "the complex of animals and vegetation has changed since horses were extirpated from North America". It also stated that the distinction between native or non-native was not the issue, but rather the "priority that BLM gives to free-ranging horses and burros on federal lands, relative to other uses".[108]

Mustang supporters advocates for the BLM to rank mustangs higher in priority than it currently does, arguing that too little forage is allocated to mustangs as opposed to cattle and sheep.[109] Ranchers and others affiliated with the livestock industry favor a lower priority, arguing essentially that their livelihoods and rural economies are threatened because they depend upon the public land forage for their livestock.[110]

The debate as to what degree mustangs and cattle compete for forage is multifaceted. Horses are adapted by evolution to inhabit an ecological niche characterized by poor quality vegetation.[111] Advocates assert that most current mustang herds live in arid areas which cattle cannot fully utilize due to the lack of water sources.[112] Mustangs can cover vast distances to find food and water;[113] advocates assert that horses range 5–10 times as far as cattle to find forage, finding it in more inaccessible areas.[109] In addition, horses are "hindgut fermenters", meaning that they digest nutrients by means of the cecum rather than by a multi-chambered stomach.[114] While this means that they extract less energy from a given amount of forage, it also means that they can digest food faster and make up the difference in efficiency by increasing their consumption rate. In practical effect, by eating greater quantities, horses can obtain adequate nutrition from poorer forage than can ruminants such as cattle, and so can survive in areas where cattle will starve.[111]

However, while the BLM rates horses by animal unit (AUM) to eat the same amount of forage as a cow–calf pair, 1.0, studies of horse grazing patterns indicate that horses probably consume forage at a rate closer to 1.5 AUM.[115] Modern rangeland management also recommends removing all livestock[lower-alpha 16] during the growing season to maximize re-growth of the forage. Year-round grazing by any non-native ungulate will degrade it,[116] particularly horses whose incisors allow them to graze plants very close to the ground, inhibiting recovery.[107]

Management and adoption

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was tasked by Congress with protecting, managing, and controlling free-roaming horses and burros under the authority of the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 to ensure that healthy herds thrive on healthy rangelands under the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act.[117] Difficulty arises because mustang herd sizes can multiply rapidly, increasing up to and possibly by over 20% every year, so population control presents a challenge. When unmanaged, population numbers can outstrip forage available, leading to starvation.[118]

There are few predators in the modern era capable of preying on healthy adult mustangs,[119] and for the most part, predators capable of limiting the growth of feral mustang herd sizes are not found in the same habitat as most modern feral herds.[120] Although wolves and mountain lions are two species known to prey on horses and in theory could control population growth,[120] in practice, predation is not a viable population control mechanism. Wolves were historically rare in, and currently do not inhabit, the Great Basin,[121] where the vast majority of mustangs roam. While they are documented to prey on feral horses in Alberta, Canada, there is no known documentation of wolf predation on free-roaming horses in the United States.[120] Mountain lions have been documented to prey on feral horses in the U.S., but in limited areas and small numbers,[119] and mostly foals.[120]

One of the BLM's key mandates under the 1971 law and amendments is to maintain AML of wild horses and burros in areas of public rangelands where they are managed by the federal government.[122] Control of the population to within AML is achieved through a capture program. There are strict guidelines for techniques used to round up mustangs. One method uses a tamed horse, called a "Judas horse", which has been trained to lead wild horses into a pen or corral. Once the mustangs are herded into an area near the holding pen, the Judas horse is released. Its job is then to move to the head of the herd and lead them into a confined area.[123]

Since 1978, captured horses have been offered for adoption to individuals or groups willing and able to provide humane, long-term care after payment of an adoption fee; the base fee is $125. Adopted horses are still protected under the Act, for one year after adoption, at which point the adopter can obtain title to the horse. Horses that could not be adopted were to be humanely euthanized.[117][124] Instead of euthanizing excess horses, the BLM began keeping them in "long term holding", an expensive alternative[125] that can cost taxpayers up to $50,000 per horse over its lifetime.[94] On December 8, 2004, a rider amending the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act was attached to an appropriation bill before the Congress by former Senator Conrad Burns. This modified the adoption program to also allow the unlimited sale of captured horses that are "more than 10 years of age", or that were "offered unsuccessfully for adoption at least three times". Since 1978, there had been specific language in the Act forbidding the BLM from selling the horses to those would take them to slaughter, but the Burns Amendment removed that language.[117][126] In order to prevent horses being sold to slaughter, the BLM has implemented policies limiting sales and requiring buyers to certify they will not take the horses to slaughter.[56] In 2017, the Trump administration began pushing Congress to remove barriers to implementing both the option to euthanize and sell excess horses.[127]

Despite such means as the Extreme Mustang Makeover, a promotional competition that gives trainers 100 days to gentle and train 100 mustangs, which are then adopted through an auction, to try increase the number of horses adopted,[128] adoption numbers do not come close to finding homes for the excess horses. Ten thousand foals were expected to be born on range in 2017,[94] whereas only 2500 horses were expected to be adopted. Alternatives to roundups for on range population control include fertility control, either by PZP injection or spaying mares,[127] culling and natural regulation.[129]

Captured horses are freeze branded on the left side of the neck by the BLM, using the International Alpha Angle System, a system of angles and alpha-symbols that cannot be altered. The brands begin with a symbol indicating the registering organization, in this case the U.S. Government, then two stacked figures indicating the individual horse's year of birth, then the individual registration number. Captured horses kept in sanctuaries are also marked on the left hip with four inch-high Arabic numerals that are also the last four digits of the freeze brand on the neck.[130]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Feral horses from America. |

Notes

- Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalskii) is possibly the only remaining true extant wild horse, but recent studies suggest Przewalski's horse may have been briefly domesticated millennia ago.[2][3]

- Another source defines mostrenco as 'wild, stray, ownerless'.[5]

- Examples include the Herd Management Areas in California and Idaho.[13][14]

- See, e.g., High Rock[22] and Carter Reservoir HMAs, California;[23] Twin Peaks HMA, California/Nevada;[24] and Black Mountain HMA, Idaho.[25]

- Some horses in the Pryor range are said to be under 14 hands (56 inches, 142 cm),[27] Horses estimated at up to 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm) are found at HMAs such as Devils Garden Wild Horse Territory, California,[28] and Challis HMA, Idaho.[26]

- Apache was a Pueblo word meaning 'enemy', and some early accounts referred to all hostile tribes generically as "Apaches" regardless of which tribe was involved.[41]

- Horses did not arrive in the Great Basin until the 1850s.[44]

- The Western Shoshone occupied the interior of the Great Basin, and did not have access to horses until after 1850.[44]

- It was there and the southern Great Plains where Dobie stated the "Spanish horses found vast American ranges corresponding in climate and soil to the arid lands of Spain, northern Africa and Arabia in which they originated".[51]

- The OED cites Sources Mississ. III 273 for Pike; and "Journal, 5 Sept." in Texas State Historical Association Quarterly (1904) VII. 300, for Austin.[55]

- Tom L. McKnight c. 1929–2004, PhD Wisconsin 1955, professor of geography, UCLA.[59]

- "Ed" de Steiguer PhD, professor at the University of Arizona.[61]

- The area was also known as the "Wild Horse Desert"[65] or "Mustang Desert".[60]

- Although for the most part, the Native Americans in the Great Basin Desert did not have horses, the Bannocks were an offshoot of the Northern Paiute in southern Oregon and northwest Oregon[44] that developed a horse culture. They may have the tribe that attacked a member of the Ogden party at the Humboldt Sinks in 1829.[70]

- A few hundred free-roaming horses survive in Alberta and British Columbia

- "Livestock" in this context includes sheep, cattle, and horses.[116]

References

- "The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, as amended" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- "When Is 'Wild' Actually 'Feral'?". The Last Wild Horse: The Return of Takhi to Mongolia Bio Feature. American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- "Ancient DNA upends the horse family tree". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. February 22, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- "mustang, n.". Oxford English Dictionary Online (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2003.

- Corominas, J.; Pascual, J. A. (1981). "mostrenco". Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico (in Spanish). Madrid: Gredos s.v.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". EtymOnline.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- "Mesta, n.". Oxford English Dictionary Online (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2001.

- Jones, C. Allan (2005). Texas Roots: Agriculture and Rural Life Before the Civil War. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 74–75.

- Latta, Frank Forrest (1980). Joaquín Murrieta and His Horse Gangs. Santa Cruz, California: Bear State Books. p. 84.

- Hendricks, Bonnie L. (2007). International Encyclopedia of Horse Breeds (paperback ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 18–19, 301–303. ISBN 9780806138848. Archived from the original on December 28, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Breeds of Livestock – Mustang (Horse)". ANSI.OKState.edu. Department of Animal Science, Oklahoma State University. May 7, 2002. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- Twombly, Matthew; Baptista, Fernando G.; Healy, Patricia (March 2014). "Return of a Native: How the horse came home to the New World". National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- "California–Wild Horses & Burros". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- "Idaho's Wild Horse Program". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- "Idaho's Wild Horse Program". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- "ROCKY HILLS HMA". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. January 9, 2008. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- "CALLAGHAN HMA". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. January 9, 2008. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- "dividebasin". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. March 5, 2013. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "5". Genetic Diversity in Free-ranging Horse and Burro Populations (Report). Washington DC: National Research Council, National Academies Press. 2013. pp. 144–145. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- "5". Genetic Diversity in Free-ranging Horse and Burro Populations (Report). Washington DC: National Research Council, National Academies Press. 2013. p. 152. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- Cothran, E. Gus. "Genetic Analysis of the Pryor Mountains HMA, MT" (PDF). Department of Veterinary Integrative Bioscience, Texas A&M University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015 – via BLM.gov.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Carter Reservoir Herd Management Area (CA-269)". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Twin Peaks Herd Management Area (CA-242)". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Black Mountain HMA". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. March 18, 2015. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Challis HMA". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. August 12, 2013. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Pomeranz, Lynne; Massingham, Rhonda (2006). Among wild horses a portrait of the Pryor Mountain mustangs. North Adams, Massachusetts: Storey Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 9781612122137.

- "Devils Garden Wild Horse Territory, Wild Horses & Burros, Bureau of Land Management California". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. October 24, 2013. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Bennett, p. 14

- Bennett, p. 193

- Bennett, p. 205

- Haines, "Where Did the Plains Indians Get Their Horses?", January 1938

- Bennett, pp. 329–331

- Haines, "The Northward Spread of Horses Among the Plains Indians", July 1938, p. 430

- Bennett, 345

- Lobell, Jarrett A.; Powell, Eric A. (July–August 2015). "The Story of the Horse". Archaeology. p. 33. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- Haines, "Where Did the Plains Indians Get Their Horses?", January 1938, p. 117

- de Steiguer, p. 70

- Bennett, p. 330

- "Horses Spread Across the Land". A Song for the Horse Nation. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- Dobie, p. 36

- Haines, "The Northward Spread of Horses Among the Plains Indians", July 1938, p. 431

- "Horse Trading Among Nations". A Song for the Horse Nation. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- Kuiper, Kathleen, ed. (2011). American Indians of California, the Great Basin, and the Southwest. Britannica Educational Publications. p. 46. ISBN 9781615307128.

- Bennett, p. 388

- McKnight, pp. 511–513

- Dobie, p. 41

- de Steiguer, pp. 73–74

- Bennett, p. 374

- de Steiguer, p. 76

- Dobie, p. 23

- Bennett, pp. 384–385

- de Steiguer, p. 74

- de Steiguer, p. 75

- Simpson, J. A. (1989). "Mustang". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0198612223.

- "Myths and Facts". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. September 19, 2016. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Ryden, America's Last Wild Horses, p. 129

- Wyman, p. 91

- "Tom McKnight obituary". AAG.org. Association of American Geographers. 2004. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- Dobie, p. 108

- "J. Edward de Steiguer". deSteiguer.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- de Steiguer, loc2253, Chapter 7: America sweeps onto the Great Plains

- Ford, John Salmon (2010) [1987]. Rip Ford's Texas. University of Texas Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-292-77034-8.

- Dobie, pp. 108–109

- Givens, Murphy (November 23, 2011). "Chasing mustangs in the Wild Horse Desert". Corpus Christi Caller Times. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- Grant, Ulysses (1995). Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. Dover Publications. pp. 28, 29. ISBN 978-0-486-28587-0.

- Dobie, p. 316

- Morin, Honest Horses, p. 3"

- Berger, Wild Horses, p. 36.

- Wheeler, Sessions S. (2003). Nevada's Black Rock Desert. Caxton Press. p. 98. ISBN 9780870045394.

- Young and Sparks, Cattle in the Cold Desert, p. 215

- Young and Sparks, Cattle in the Cold Desert, pp. 216–217

- de Steiguer, loc2595

- "Mustang Country Wild Horses & Burros" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Land Management. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2015.

- Cruise, David; Griffiths, Alison (2010). Wild Horse Annie and the Last of the Mustangs: The Life of Annie Johnston. Simon & Schuster. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4165-5335-9.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dobie, p. 321

- Amaral, Mustang, p. 12

- Wyman, p. 161

- Sherrets

- blm_admin (August 10, 2016). "About: History of the BLM". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Curnutt, Jordan (2001). Animals and the Law: A Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 142. ISBN 9781576071472.

- "History of the Program: The Wild Horse Annie Act". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. September 19, 2016. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Use of aircraft or motor vehicles to hunt certain wild horses or burros; pollution of watering holes". Archived from the original on January 27, 2016.

- Mangum, A. J. (December 2010). "The Mustang Dilemma". Western Horseman. p. 77.

- "Background Information on HR297" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- "Welcome to Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge". FWS.gov. Pacific Region Web Development Group, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Managing Feral Horses on National Park Service Lands". TheHorse.com. April 2, 2015. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Horses of Theodore Roosevelt National Park". NPS.gov. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Proceedings: National Wild Horse Forum – Nevada Agricultural Publications". ContentDM.Library.UNR.edu. Reno: University of Nevada Library. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Wild Horse and Burro Territories". Archived from the original on January 18, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- blm_admin (September 19, 2016). "Programs: Wild Horse and Burro: Herd Management: Maintaining Range and Herd Health". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- jlutterman@blm.gov (October 19, 2016). "Programs: Wild Horse and Burro: About: Data: Population Estimates". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Masters. "Mustangs in Crisis". p. 1. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018.

- blm_admin (September 19, 2016). "Programs: Wild Horse and Burro: Herd Management: Herd Management Areas". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Equidae". Research.AMNH.org. American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016.

- Weinstock, J.; et al. (2005). "Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of pleistocene horses in the New World: A molecular perspective". PLoS Biology. 3 (8): e241. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030241. PMC 1159165. PMID 15974804.

- Heintzman, Peter D.; Zazula, Grant D.; MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Scott, Eric; Cahill, James A.; McHorse, Brianna K.; Kapp, Joshua D.; Stiller, Mathias; Wooller, Matthew J.; Orlando, Ludovic; Southon, John; Froese, Duane G.; Shapiro, Beth (2017). "A new genus of horse from Pleistocene North America". eLife. 6. doi:10.7554/eLife.29944. PMC 5705217. PMID 29182148.

- Barrón-Ortiz, Christina I.; Rodrigues, Antonia T.; Theodor, Jessica M.; Kooyman, Brian P.; Yang, Dongya Y.; Speller, Camilla F. (August 17, 2017). Orlando, Ludovic (ed.). "Cheek tooth morphology and ancient mitochondrial DNA of late Pleistocene horses from the western interior of North America: Implications for the taxonomy of North American Late Pleistocene Equus". PLoS One. 12 (8): e0183045. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183045. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5560644. PMID 28817644.

- Orlando, Ludovic; Ginolhac, Aurélien; Zhang, Guojie; Froese, Duane; Albrechtsen, Anders; Stiller, Mathias; Schubert, Mikkel; Cappellini, Enrico; Petersen, Bent; Moltke, Ida; Johnson, Philip L. F. (26 June 2013). "Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse". Nature. 499 (7456): 74–78. doi:10.1038/nature12323. ISSN 0028-0836.

- "Ice Age Horses May Have Been Killed Off by Humans". National Geographic News. May 1, 2006. Archived from the original on June 26, 2006.

- Haile, James; Frose, Duane G.; MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Roberts, Richard G.; Arnold, Lee J.; Reyes, Alberto V.; Rasmussen, Morton; Nielson, Rasmus; Brook, Barry W.; Robinson, Simon; Dumoro, Martina; Gilbert, Thomas P.; Munch, Kasper; Austin, Jeremy J.; Cooper, Alan; Barnes, Alan; Moller, Per; Willerslev, Eske (2009). "Ancient DNA reveals late survival of mammoth and horse in interior Alaska". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 6.

- Masters, Ben (February 6, 2017). "Wild Horses, Wilder Controversy". National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- "4". Wild and Free Roaming Horses and Burros: Final Report (Report). Washington DC: National Research Council, National Academies Press. 1982. pp. 11–13. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017.

- Kirkpatrick, Jay F.; Fazio, Patricia M. Wild Horses as Native North American Wildlife (Report). Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- "The Surprising History of America's Wild Horses". LiveScience.com. July 24, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- Final Position Statement: Feral Horses and Burros in North America (PDF) (Report). The Wilderness Society. July 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2016.

- "8". Social Considerations in Managing Free-Ranging Horses and Burros (Report). Washington DC: National Research Council, National Academies Press. 2013. pp. 240–241. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018.

- "FAQ". American Wild Horse Campaign. January 31, 2015. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Bellisle, Martha. "Legislative battle brews over Nevada's wild horses". HorseAid's Bureau of Land Management News. International Generic Horse Association. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- Budiansky, p. 31

- "Wild Horses and the Ecosystem". American Wild Horse Campaign. October 2, 2012. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Budiansky, p. 186

- Budiansky, p. 29

- "7". Establishing and Adjusting Appropriate Management Levels (Report). Washington DC: National Research Council, National Academies Press. 2013. p. 207. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018.

- Davies, K.W.; Vavra, M.; Schultz, B.; Rimbey, M. (2014). "Implications of Longer Term Rest from Grazing in the Sagebrush Steppe". Journal of Rangeland Applications. 1: 14–34. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Nazzaro, Robin N. (October 2008). Effective Long-Term Options Needed to Manage Unadoptable Wild Horses (PDF) (Report). Government Accountability Office. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015.

- Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program: A Way Forward (Report). Washington DC: National Academies Press. 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- Turner, John W., Jr.; Morrison, Michael L. (2008). "Influence of Predation by Mountain Lions on Numbers and Survivorship of a Feral Horse Population". Southwestern Naturalist. 46 (2): 183–190. doi:10.2307/3672527. JSTOR 3672527. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program: A Way Forward (Report). Washington DC: National Academies Press. 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- Grayson, Donald K. (1993). The Desert's Past a Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program: A Way Forward (Report). Washington DC: National Academies Press. 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- French, Brett (September 3, 2009). "Controversial roundup of mustangs begins in Pryor Mountains". Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- "Adoption and Purchase Frequently Asked Questions". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. September 19, 2016. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Nazzaro, Robin N. (October 2008). Effective Long-term Options Needed to Manage Unadoptable Wild Horses (PDF) (Report). U.S. Government Accountability Office. pp. 59–60. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015.

- "The "Final Solution" for Wild Horses?". KBR Horse Page. Knightsen, California / Stagecoach, Nevada: Kickin' Back Ranch. 2004. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Masters. "Mustangs in Crisis". Western Horseman. Morris Communications. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018.

- "The Extreme Mustang Makeover". Archived from the original on September 1, 2009.

- Masters. "Mustangs in Crisis". Archived from the original on March 9, 2018.

- "Freezemarks". BLM.gov. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. August 29, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

Sources

- Bennett, Deb (1998). Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship (1st ed.). Solvang, California: Amigo Publications. ISBN 978-0-9658533-0-9.

- Budiansky, Stephen (1997). The Nature of Horses: Exploring Equine Evolution, Intelligence, and Behavior. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780684827681.

- de Steiguer, J. Edward (2011). Wild Horses of the West: History and Politics of America's Mustangs. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816528264.

- Dobie, J. Frank (2005) [1952]. The Mustangs (paperback ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780803266506.

- Haines, Francis (July 1938). "The Northward Spread of Horses Among the Plains Indians" (PDF). American Anthropologist. Wiley. 40 (3): 429–437. doi:10.1525/aa.1938.40.3.02a00060. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- Haines, Francis (January 1938). "Where Did the Plains Indians Get Their Horses?". American Anthropologist. 40 (1): 112–117. doi:10.1525/aa.1938.40.1.02a00110. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- McKnight, Tom L. (October 1959). "The Feral Horse in Anglo-America". Geographical Review. 49 (4): 506–525. doi:10.2307/212210. JSTOR 212210.

- Masters, Ben (August 9, 2017). "Mustangs in Crisis". Western Horseman.

- Committee to Review the Bureau of Land Management Wild Horse and Burro Management Program (2013). Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program: A Way Forward. Washington DC: Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council, National Academies Press. ISBN 9780309264976.

- Sherrets, Harold (1984). "The Taylor Grazing Act, 1934-1984, 50 Years of Progress, Impacts of Wild Horses on Rangeland Management". Boise: Bureau of Land Management, Idaho State Office.

- Wyman, Walker D. (1966) [1945]. The Wild Horse of the West. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803252233.

Further reading

- Roe, Frank Gilbert (1974) [1955]. The Indian and the Horse. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Luís, Cristina; Bastos-Silveira, Cristiane; Cothran, E. Gus; Oom, Maria do Mar (December 21, 2005). "Iberian Origins Of New World Horse Breeds". Journal of Heredity. 97 (2): 107–113. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj020. PMID 16489143. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- Morin, Paula (2006) Honest Horses: Wild Horses of the Great Basin. Reno: University of Nevada Press

- Nimmo, D. G.; Miller, K. K. (2007) Ecological and human dimensions of management of feral horses in Australia: A review. Wildlife Research, 34, 408–417

- Text of Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971