Muskmelon

Muskmelon (Cucumis melo) is a species of melon that has been developed into many cultivated varieties. These include smooth-skinned varieties such as honeydew, Crenshaw, and casaba, and different netted cultivars (cantaloupe, Persian melon, and Santa Claus or Christmas melon). The large number of cultivars in this species approaches that found in wild cabbage, though morphological variation is not as extensive. It is a fruit of a type called pepo.

| Muskmelon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Cucurbitales |

| Family: | Cucurbitaceae |

| Genus: | Cucumis |

| Species: | C. melo |

| Binomial name | |

| Cucumis melo | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

The origin of muskmelons is not known. Research has revealed that seeds and rootstocks were among the goods traded along the caravan routes of the Ancient World. Some botanists consider muskmelons native to the Levant and Egypt, while others place their origin in India or Central Asia.[2] Still others support an African origin, and in modern times wild muskmelons can still be found in some African countries.[3]

Background

The muskmelon is an annual, trailing herb.[2] It grows well in subtropical or warm, temperate climates.[3] Muskmelons prefer warm, well-fertilized soil with good drainage that is rich in nutrients,[2] but are vulnerable to downy mildew and anthracnose. Disease risk is reduced by crop rotation with non-cucurbit crops, avoiding crops susceptible to similar diseases as muskmelons. Cross pollination has resulted in some varieties developing resistance to powdery mildew.[4] Insects attracted to muskmelons include the cucumber beetle, melon aphid, melonworm moth and the pickleworm.[4]

Genetics

| NCBI genome ID | 10697 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| Genome size | 374.77 Mb |

| Number of chromosomes | 12 |

| Year of completion | 2012 |

Muskmelons are monoecious plants. They do not cross with watermelon, cucumber, pumpkin, or squash, but varieties within the species intercross frequently.[5] The genome of Cucumis melo was first sequenced in 2012.[6] Some authors treat C. melo as having two subspecies, C. melo agrestis and C. melo melo. Variants within these subspecies fall into groups whose genetics largely agree with their phenotypic traits, such as disease resistance, rind texture, flesh color, and fruit shape. Variants or landraces (some of which were originally classified as species; see the synonyms list to the right) include C. melo var. acidulus, adana, agrestis, ameri, cantalupensis, chandalak, chate, chinensis, chito, conomon, dudaim, flexuosus, inodorus, makuwa, momordica, reticulatus and tibish.

Not all varieties are sweet melons. The snake melon, also called the Armenian cucumber and Serpent cucumber, is a non-sweet melon found throughout Asia from Turkey to Japan.[7][3] It is similar to a cucumber in taste and appearance.[8] Outside Asia, snake melons are grown in the United States, Italy, Sudan and parts of North Africa, including Egypt.[3] The snake melon is more popular in Arab countries.[8]

Other varieties grown in Africa are bitter, cultivated for their edible seeds.[3]

For commercially grown varieties certain features like protective hard netting and firm flesh are preferred for purposes of shipping and other requirements of commercial markets.[4]

Nutrition

Per 100 gram serving, cantaloupe melons provide 34 calories and are a rich source (20% or more the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin A (68% DV) and vitamin C (61% DV), with other nutrients at a negligible level.[9] Melons are 90% water and 9% carbohydrates, with less than 1% each of protein and fat.[9]

Uses

In addition to their consumption when fresh, melons are sometimes dried. Other varieties are cooked, or grown for their seeds, which are processed to produce melon oil. Still other varieties are grown only for their pleasant fragrance.[10] The Japanese liqueur, Midori, is flavored with muskmelon.

History

There is debate among scholars whether the abattiach in The Book of Numbers 11:5 refers to a muskmelon or a watermelon.[11] Both types of melon were known in Ancient Egypt and other settled areas. Some botanists consider muskmelons native to the Levant and Egypt, while others place the origin in Persia, India or Central Asia, but the origin is uncertain. Researchers have shown that seeds and rootstocks were among the goods traded along the caravan routes of the Ancient World.[2] Several scientists support an African origin, and in modern times wild muskmelons can still be found in several African countries in East Africa like Ethiopia, Somalia and Tanzania.[3]

Melon was domesticated in West Asia and over time many cultivars developed with variety in shape and sweetness. Iran, India, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and China become centers for melon production.[3] Muskmelons were consumed in Ancient Greece and Rome.[12]

Gallery

.jpg)

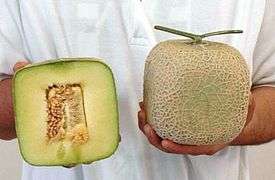

Japanese "crown melon" intended as a high-priced gift: The pictured crown melon is 6300 yen, or about US$59

Japanese "crown melon" intended as a high-priced gift: The pictured crown melon is 6300 yen, or about US$59 'Squared melon' grown in Atsumi District, Aichi Japan, known as kakumero

'Squared melon' grown in Atsumi District, Aichi Japan, known as kakumero The Armenian cucumber, despite the name, is actually a type of muskmelon.

The Armenian cucumber, despite the name, is actually a type of muskmelon. Melon vendor in Samarkand (between 1905 and 1915)

Melon vendor in Samarkand (between 1905 and 1915)

See also

- Bailan melon

- Barattiere – a landrace variety of muskmelon found in Southern Italy

- Carosello – a landrace variety of muskmelon found in Southern Italy

- Crane melon

- Hami melon

- Korean melon

- Melon ball

- Melon Day

- Montreal melon

- Sugar melon

References

- The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species, retrieved 23 January 2016

- Swenson, Allan A. (1995). Plants of the Bible: And How to Grow Them. Citadel Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780806516158. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Grubben, G. J. H. (2004). Vegetables. PROTA Foundation. p. 243. ISBN 9789057821479. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Beattie, James Herbert (1951). Muskmelons. Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Martin Anderson, Texas AgriLife Extension Service. "Muskmelons Originated in Persia - Archives - Aggie Horticulture". tamu.edu.

- Jordi Garcia-Mas (2012). "The genome of melon (Cucumis melo L.)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (29): 11872–11877. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10911872G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205415109. PMC 3406823. PMID 22753475.

- Ashworth, Suzanne (2012-10-31). Seed to Seed: Seed Saving and Growing Techniques for the Vegetable Gardener. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 9780988474901. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Goldman, Amy (January 2002). Melons: For the Passionate Grower. Artisan Books. p. 112. ISBN 9781579652135. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "Nutrition Facts for 100 g of melons, cantaloupe, raw [includes USDA commodity food A415]". Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, version SR-21. 2014.

- National Research Council (2008-01-25). "Melon". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume III: Fruits. Lost Crops of Africa. 3. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/11879. ISBN 978-0-309-10596-5. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- "We remember the fish, which we did eat in Egypt freely; the cucumbers, and the melons, and the leeks, and the onions, and the garlick" Numbers 11:5

- Ensminger, Marion Eugene (1993-11-09). Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia, Two Volume Set. CRC Publisher. ISBN 9780849389801. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Cucumis melo L. – Purdue University, Center for New Crops & Plant Products.

- Sorting Cucumis names – Multilingual multiscript plant name database

- Cook's Thesaurus: Melons – Varietal names and pictures