Murray MacLehose, Baron MacLehose of Beoch

Crawford Murray MacLehose, Baron MacLehose of Beoch, KT, GBE, KCMG, KCVO, DL (Chinese: 麥理浩, 16 October 1917 – 27 May 2000), was a British politician, diplomat and the 25th Governor of Hong Kong, from 1971 to 1982. He was the longest-serving governor of the colony, with four successive terms in office.[1]

The Lord MacLehose of Beoch KT GBE KCMG KCVO DL | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 25th Governor of Hong Kong | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 November 1971 – 8 May 1982 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Colonial Secretary | Hugh Norman-Walker Denys Roberts | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief Secretary | Denys Roberts Jack Cater Philip Haddon-Cave | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | David Trench | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Edward Youde | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 21 May 1982 – 27 May 2000 Life Peerage | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 16 October 1917 Glasgow, Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 27 May 2000 (aged 82) Ayrshire, Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Alloway Parish Church, Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Diplomat, colonial administrator | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 麥理浩 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 麦理浩 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Early life and career

Murray MacLehose was born in Glasgow, Scotland in October 1917 as the second child of Hamish Alexander MacLehose and Margaret Bruce Black. He attended Rugby School in 1931 and Balliol College, Oxford.

During World War II, while under the cover of being the British vice-consul, MacLehose[2] trained Chinese guerrillas to operate behind Japanese lines to carry out sabotage.

MacLehose was principal private secretary to Foreign Secretary George Brown in the late 1960s.

His career almost stalled when he left a copy of a confidential telegram in a bank in 1967. The document, from British Prime Minister Harold Wilson to US President Lyndon B. Johnson concerning the Vietnam War, was turned in by another British diplomat who found it. Wilson and Brown prevented an investigation of this security breach, because they appreciated MacLehose's ability, thus saving his career.[3] MacLehose was appointed the British Ambassador to South Vietnam in 1967.[3]

Before being appointed as Governor of Hong Kong in 1971, he served in the British Embassy in Beijing and as Ambassador to Denmark.

Governor of Hong Kong

MacLehose became Governor of Hong Kong in November 1971, holding this position until May 1982, making him Hong Kong's longest-serving governor; his 10 years and 6 months in office exceeding Sir Alexander Grantham's previous record by one month. He was widely and affectionately known as "Jock the Sock", in reference both to his Scottish heritage and to his name, 'hose' being a word meaning sock or stocking.

MacLehose stood well over six feet tall. He avoided wearing his gubernatorial uniform, as he felt very ill at ease in it.

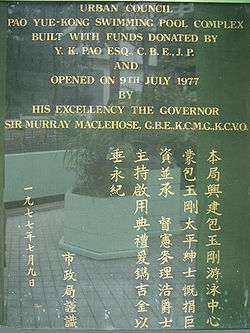

A diplomat with a British Labour Party background,[4] MacLehose introduced a wide range of reforms during his time in office that laid the foundation of modern Hong Kong as a cohesive, self-aware society. He had Chinese recognised as an official language for communication, alongside English. He greatly expanded welfare and set up a massive public housing programme. Under massive public pressure, he created the ICAC to root out corruption. By establishing the District Boards, he greatly improved government accountability.[5] He oversaw the construction of the Mass Transit Railway, Hong Kong's transportation backbone, and other major infrastructure projects. On his watch, community and arts facilities were expanded, and public campaigns, such as against litter and violent crime, were introduced.

These changes required approval from the UK Government Treasury for increased expenditure, and it was against some opposition that, in his first two years in office, Hong Kong government expenditure grew by over 50%.[6]

MacLehose was convinced that China would eventually reclaim Hong Kong and opposed any significant move towards constitutional democracy in Hong Kong.[7]

Other notable policies

Other major policies introduced during the MacLehose era included:

- The introduction of 9 years of compulsory education.[8]

- The introduction of the Ten-year Housing Programme in 1972 to alleviate housing problems.[9]

- The establishment of satellite 'new towns',[10] such as Sha Tin and Tuen Mun.

- The establishment of the Country Parks.[10]

- The introduction and approval of a Labour Ordinance.[11]

- The establishment of the social assistance scheme.[12]

- The construction of the Mass Transit Railway.[13]

- An expansion of community facilities.[14]

- The adoption of Chinese as an official language.[15]

- The introduction of paid holidays.[16]

- An increase in social service provision for the elderly.[12]

- The introduction of infirmity and disability allowances.[17]

- The introduction of redundancy payments for workers.[16]

- The introduction of the Home Ownership Scheme to encourage owner-occupation.[18]

- The introduction of a major rehabilitation programme for the disabled and disadvantaged.[19]

- An increase in the number of schools and hospitals.[20]

- The introduction of Criminal and Law Enforcement Injuries Compensation.[21]

- The introduction of Traffic Accident Victims Assistance.[21]

- The introduction of special needs allowances for the elderly.[21]

- The introduction of sickness allowances for eligible manual and lower-paid non-manual workers.[21]

- The introduction of weekly rest days.[21]

- The introduction of Labour Tribunals.[21]

- The establishment of the Junior Secondary Education Assessment (JSEA) system to increase the number of subsidised places in senior secondary education.[21]

- The establishment of Geotechnical Engineering Office (part of Civil Engineering and Development Department) to ensure safeties of slopes and hillside to avoid further loss of lives due to landslides and slips of Sau Mau Ping in 1972 and 1976.[22]

- The establishment of the Jubilee Sports Centre

- The establishment of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts

Hong Kong sovereignty negotiations

In 1979, MacLehose raised the question of Britain's 99-year lease of the New Territories (an area that encompasses all territories north of Boundary Street on the Kowloon Peninsula), with Deng Xiaoping. The talks, although inconclusive at the time, eventually involved top British Government officials and paved the way for the handover of the Hong Kong in its entirety, including those parts ceded to the UK in perpetuity, to the People's Republic of China on 1 July 1997.

Post-governorship and later life

After his governorship ended in 1982, MacLehose was made a life peer as Baron MacLehose of Beoch, of Maybole in the District of Kyle and Carrick and of Victoria in Hong Kong, later that year. In 1983, MacLehose was made a Knight of the Thistle. In 1992 he was awarded an honorary doctorate (LLD) by the University of Hong Kong.[23] When he was 80 years old, he, Sir Edward Heath and Lord Howe, attended the official swearing-in ceremony of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region's Chief Executive on 1 July 1997, which was boycotted by the British Government.[7]

Honours and recognition

- Knight of the Thistle (KT) (1983)[24]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (GBE) (1976)[25]

- Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (KCMG) (1971)[26]

- Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO) (1975)[27]

- Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (CMG) (1964)[28]

- Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) (1946)[29]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Hong Kong

- Life Peerage (1982) (Barony of MacLehose of Beoch, of Maybole in the District of Kyle and Carrick and of Victoria in Hong Kong)[30]

- The 100-kilometre MacLehose Trail, stretching from Sai Kung Peninsula to Tuen Mun in the New Territories, was named after him (Maclehose was an enthusiastic hiker)

- The MacLehose Medical Rehabilitation Centre, the MacLehose Dental Centre, the Lady MacLehose Holiday Village, and the Sir Murray MacLehose Trust Fund was also named to commemorate him or his wife

References

- A & C Black (2000). "MacLEHOSE OF BEOCH, Baron". Who Was Who, online edition. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- p. 150 The Man Who Loved China by Simon Winchester, 2008

- Peter Graff, Mislaid MacLehose cable reveals UK efforts to end Vietnam War Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Standard, 2 November 2007

- The East Asian welfare model: welfare Orientalism and the state by Roger Goodman, Gordon White, and Huck-ju Kwon

- District Administration Hong Kong Government

- Fitzpatrick, Liam (13 November 2006). "Sir Murray MacLehose". 60 Years of Asian Heroes. Time. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- "Obituaries: Lord MacLehose of Beoch". The Daily Telegraph. 31 May 2000. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Social policy reform in Hong Kong and Shanghai: a tale of two cities by Linda Wong, Lynn T. White, and Shixun Gui

- Hong Kong's housing policy: a case study in social justice by Betty Yung

- Carroll, John Mark (2007). A concise history of Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-3422-3.

- Hong Kong employment law: a practical guide by Pattie Walsh Labour ordinance

- Professional ideologies and preferences in social work: a global study by Idit Weiss and John Dixon

- Frommer's Hong Kong by Beth Reiber

- Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years by University of Hong Kong

- Language policy, culture, and identity in Asian contexts by Amy Tsui and James W. Tollefson

- Hong Kong's tortuous democratization: a comparative analysis by Ming Sing

- Understanding the Political Culture of Hong Kong: The Paradox of Activism and Depolitization by Wai-man Lam

- Hong Kong, China: growth, structural change, and economic stability during the transition by John Dodsworth and Dubravko Mihaljek

- Rehabilitation: A Life's Work by Harry Fang Sinyang and Lawrence Jeffery

- Understanding the political culture of Hong Kong: the paradox of activism and depoliticization by Wai-Man Lam

- Promoting prosperity: the Hong Kong way of social policy by Catherine M. Jones

- Computer Animation of the 1972 & 76 Sau Mau Ping Landslides on YouTube

- University of Hong Kong, Honorary Degrees Congregation Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "No. 49557". The London Gazette. 2 December 1983. p. 15977.

- "No. 46919". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 June 1976. p. 8031.

- "No. 45384". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 June 1971. p. 5959.

- "No. 46610". The London Gazette. 19 June 1975. p. 7843.

- "No. 43200". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1964. p. 5.

- "No. 37407". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1946. p. 16.

- "No. 48992". The London Gazette. 26 May 1982. p. 6989.

External links

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Nicholas Henderson |

Principal Private Secretary to the Foreign Secretary 1965–1967 |

Succeeded by Sir Donald Maitland |

| Preceded by Sir Peter Wilkinson |

British Ambassador to Vietnam 1967–1969 |

Succeeded by Sir John Moreton |

| Preceded by Sir Oliver Wright |

British Ambassador to Denmark 1969–1971 |

Succeeded by Sir Andrew Stark |

| Preceded by Sir David Trench |

Governor and Commander-in-Chief, Hong Kong 1971–1982 |

Succeeded by Sir Edward Youde |

.svg.png)