Multiple-camera setup

The multiple-camera setup, multiple-camera mode of production, multi-camera or simply multicam is a method of filmmaking and video production. Several cameras - either film or professional video cameras - are employed on the set and simultaneously record or broadcast a scene. It is often contrasted with a single-camera setup, which uses one camera.

Description

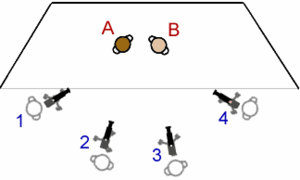

Generally, the two outer cameras shoot close-up shots or "crosses" of the two most active characters on the set at any given time, while the central camera or cameras shoot a wider master shot to capture the overall action and establish the geography of the room.[1] In this way, multiple shots are obtained in a single take without having to start and stop the action. This is more efficient for programs that are to be shown a short time after being shot as it reduces the time spent in film or video editing. It is also a virtual necessity for regular, high-output shows like daily soap operas. Apart from saving editing time, scenes may be shot far more quickly as there is no need for re-lighting and the set-up of alternative camera angles for the scene to be shot again from the different angle. It also reduces the complexity of tracking continuity issues that crop up when the scene is reshot from the different angles.

Drawbacks include a less optimized lighting setup which needs to provide a compromise for all camera angles and less flexibility in putting the necessary equipment on scene, such as microphone booms and lighting rigs. These can be efficiently hidden from just one camera but can be more complicated to set up and their placement may be inferior in a multiple-camera setup. Another drawback is in the usage of recording capacity, as a four-camera setup may use (depending on the cameras involved) up to four times as much film (or digital storage space) per take compared with a single-camera setup.

A multiple-camera setup will require all cameras to be synchronous to assist with editing and to avoid cameras running at different scan rates, with the primary methods being SMPTE timecode and Genlock.[2]

Film

Most films use a single-camera setup,[3] but in recent decades larger films have begun to use more than one camera on set, usually with two cameras simultaneously filming the same setup. However, this is not a true multiple-camera setup in the television sense.

Some films will run multiple cameras, perhaps four or five, for large, expensive and difficult-to-repeat special effects shots, such as large explosions. Again, this is not a true multiple-camera setup in the television sense as the resultant footage will not always be arranged sequentially in editing, and multiple shots of the same explosion may be repeated in the final film - either for artistic effect or because the different shots can appear to show different explosions since they are taken from different angles.

Television

.jpg)

Multiple-camera setups are an essential part of live television.[4] The multiple-camera method gives the director less control over each shot but is faster and less expensive than a single-camera setup. In television, multiple-camera is commonly used for light entertainment, sports events, news, soap operas, talk shows, game shows, and some sitcoms.

Multiple cameras can take different shots of a live situation as the action unfolds chronologically and is suitable for shows which require a live audience. For this reason, multiple camera productions can be filmed or taped much faster than single camera. Single-camera productions are shot in takes and various setups with components of the action repeated several times and out of sequence; the action is not enacted chronologically so is unsuitable for viewing by a live audience.

In multiple-camera television, the director creates a line cut by instructing the technical director (vision mixer in UK terminology) to switch between the feeds from the individual cameras. This is either transmitted live, or recorded. In the case of sitcoms with studio audiences, this line cut is typically displayed to them on studio monitors. The line cut might be refined later in editing, as often the output from all cameras is recorded, both separately (a technique known as "ISO" recording). The camera currently being recorded to the line cut is indicated by a tally light controlled by a camera control unit (CCU) on the camera as a reference both for the talent and the camera operators, and an additional tally light may be used to indicate to the camera operator that they are being ISO recorded.

A sitcom shot with a multiple-camera setup will require a different form of script to a single-camera setup.[5]

History and use

The use of multiple film cameras dates back to the development of narrative silent films, with the earliest (or at least earliest known) example being the first Russian feature film Defence of Sevastopol (1911), written and directed by Vasily Goncharov and Aleksandr Khanzhonkov.[6] When sound came into the picture multiple cameras were used to film multiple sets at a single time. Early sound was recorded onto wax discs that could not be edited.

The use of multiple video cameras to cover a scene goes back to the earliest days of television; three cameras were used to broadcast The Queen's Messenger in 1928, the first drama performed for television.[7] The first drama performed for British television was Pirandello’s play The Man With the Flower in His Mouth in 1930, using a single camera.[8] The BBC routinely used multiple cameras for their live television shows from 1936 onward.[9][10][11]

United States

Before the pre-recorded continuing series became the dominant dramatic form on American television, the earliest anthology programs (see the Golden Age of Television) utilized multiple camera methods.

Although it is often claimed that the multiple-camera setup was pioneered for television by Desi Arnaz and cinematographer Karl Freund on I Love Lucy in 1951, other filmed television shows had already used it, including the CBS comedy The Amos 'n Andy Show, which was filmed at the Hal Roach Studios and was on the air four months earlier. The technique was developed for television by Hollywood short-subject veteran Jerry Fairbanks, assisted by producer-director Frank Telford, and first seen on the anthology series The Silver Theater, another CBS program, in February 1950.[12] Desilu's innovation was to use 35mm film instead of 16mm and to film with a multiple-camera setup before a live studio audience.

In the late 1970s, Garry Marshall was credited with adding the fourth camera (known then as the "X" Camera, and occasionally today known as the "D" Camera) to the multi-camera set-up for his series Mork & Mindy. Actor Robin Williams could not stay on his marks due to his physically active improvisations during shooting, so Marshall had them add the fourth camera just to stay on Williams so they would have more than just the master shot of the actor.[13][14] Soon after, many productions followed suit and now having four cameras (A, B, C and X/D) is the norm for multi-camera situation comedies.

Sitcoms shot with the multiple camera setup include nearly all of Lucille Ball's TV series, as well as Mary Kay and Johnny, The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, All in the Family, Three's Company, Cheers, The Cosby Show, Full House, Seinfeld, Family Matters, Mad About You, Friends, The Drew Carey Show, Frasier, Will & Grace, Everybody Loves Raymond, The King of Queens, Two and a Half Men, The Big Bang Theory, Mike & Molly, Mom, 2 Broke Girls, The Odd Couple, One Day at a Time, Man with a Plan and Bob Hearts Abishola. Many American sitcoms from the 1950s to the 1970s were shot using the single camera method, including The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, Leave It to Beaver, The Andy Griffith Show, The Addams Family, The Munsters, Get Smart, Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, Gilligan's Island, Hogan's Heroes, and The Brady Bunch. These did not have a live studio audience and by being shot single-camera, tightly edited sequences could be created, along with multiple locations, and visual effects such as magical appearances and disappearances. Multiple-camera sitcoms were more simplified but have been compared to theatre work due to its similar set-up and use of theatre-experienced actors and crew members.

While the multiple-camera format dominated US sitcom production in the 1970s and 1980s, there has been a recent revival of the single-camera format with programs such as Malcolm in the Middle (2000–2006), Scrubs (2001–2010), Entourage (2004–2011), The Office (2005–2013), My Name Is Earl (2005–2009), Everybody Hates Chris (2005–2009), It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia (2005–present), 30 Rock (2006–2013), Glee (2009–2015), Modern Family (2009–2020), The Middle (2009–2018), Community (2009–2015), Parks and Recreation (2009–2015), Raising Hope (2010–2014), Louie (2010–2015), Brooklyn Nine-Nine (2013–present), Superstore (2015–present), American Housewife (2016–present), and Young Sheldon (2017–present).

United Kingdom

The majority of British sitcoms and dramas from the 1950s to the early 1990s were made using a multi-camera format.[15] Unlike the United States, the development of completed filmed programming, using the single camera method, was limited for several decades. Instead, a "hybrid" form emerged using (single camera) filmed inserts, generally location work, which were mixed with interior scenes shot in the multi-camera electronic studio. It was the most common type of domestic production screened by the BBC and ITV. However, as technology developed, some drama productions were mounted on location using multiple electronic cameras. Many all-action 1970s programmes, such as The Sweeney and The Professionals were shot using the single camera method on 16mm film. Meanwhile, by the early 1980s the most highly-budgeted and prestigious television productions, like Brideshead Revisited (1981), had begun to use film exclusively.

By the later 1990s, soap operas were left as the only TV drama being made in the UK using multiple cameras. Television prime-time dramas are usually shot using a single-camera setup.

See also

- 3D reconstruction from multiple images

- Camera rig

- Circle-Vision 360°

- Light stage is a device used for capturing the shape, texture, and reflectance of a target, usually for the purposes of virtual cinematography. Light stages are usually a combination of and multiple camera and structured light techniques, and additionally, polarizers are included to find the subsurface scattering component of the target's skin.

- Omnidirectional camera

- Single-camera setup

References

- Scott Schaefermeyer (25 July 2012). Digital Video BASICS. Cengage Learning. pp. 189–. ISBN 1-133-41664-0.

- Norman Medoff; Edward J. Fink (10 September 2012). Portable Video: ENG & EFP. CRC Press. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-1-136-04770-1.

- Battaglio, Stephen (July 8, 2001). "TELEVISION/RADIO; Networks Rediscover the Single-Camera Sitcom". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Andrew Utterback (25 September 2015). Studio Television Production and Directing: Concepts, Equipment, and Procedures. CRC Press. pp. 163–. ISBN 978-1-317-68033-8.

- Miyamoto, Ken (21 June 2016). "Single-Camera vs. Multi-Camera TV Sitcom Scripts: What's the Difference?". ScreenCraft. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "В Салюте в День российского кино прошел показ немого фильма "Оборона Севастополя" под живое музыкальное сопровождение - Фильмы - КультурМультур". kulturmultur.com (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- "Queen's Messenger". Early Television Foundation and Museum. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Richard G Elen. "Baird versus the BBC". Baird: The Birth of Television. Transdiffusion. Archived from the original on 2010-04-17.

- "Alexandra Palace". www.earlytelevision.org. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "The Birth of Live Entertainment and Music on Television, November 6, 1936". History TV: The Restelli Collection. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Telecasting a Play", New York Times, March 10, 1940, p. 163.

- "Flight to the West?" Time, March 6, 1950.

- Anders, Charlie Jane (December 2, 2015). "Mork and Mindy Was One of the Most Unlikely Miracles in the History of Television". Gizmodo. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Kantor, Michael; Maslon, Laurence (2008). Make 'Em Laugh: The Funny Business of America. Grand Central Publishing. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-446-55575-3.

- Walker, Tim (February 2, 2011). "The return of the sitcom". The Independent. Retrieved May 12, 2017.