Multiplayer online battle arena

Multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA)[lower-alpha 1] is a subgenre of strategy video games in which each player controls a single character as part of a team competing against another team of players, usually on a map in an isometric perspective. The ultimate objective is to destroy the opposing team's main structure with the assistance of periodically-spawned computer-controlled units that march forward along set paths; however, MOBA games can have other victory conditions, such as defeating every player on the enemy team. Player characters typically have a set of unique abilities that improve over the course of a game and which contribute to the team's overall strategy. This type of multiplayer online video games originated as a subgenre of real-time strategy, though MOBA players usually do not construct buildings or units. Moreover, there are examples of MOBA games that cannot be considered RTS at all, such as Smite (2014), and Paragon.[lower-alpha 2] The genre is seen as a fusion of real-time strategy, role-playing, and action games.

| Part of a series on: |

| Strategy video games |

|---|

|

The first widely accepted "game" in the genre was Aeon of Strife (AoS), a fan-made custom map for StarCraft[1][2] in which four players each control a single powerful unit and, aided by weak computer-controlled units, compete against a stronger computer.[3] Defense of the Ancients (DotA), a community-created mod from 2003, that includes a map based on AoS for Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos and Warcraft III: The Frozen Throne, was one of the first major titles of its genre and the first MOBA for which sponsored tournaments have been held.[3] It was followed by two spiritual successors, League of Legends (2009) and Heroes of Newerth (2010), and eventually a standalone sequel, simply titled Dota 2 (2013), as well as numerous other games in the genre, such as Heroes of the Storm (2015).[4][5]

By the early 2010s, the genre has become a big part of the esports category. In 2018 alone, the prize pools reached over 60 million dollars, which is about 40% of the total esports prize pools in the same year. Major esports professional tournaments are held in venues that can hold tens of thousands of spectators and are streamed online to millions more. A strong fanbase has opened up the opportunity for sponsorship and advertising, eventually leading the genre to become a global cultural phenomenon.

Gameplay

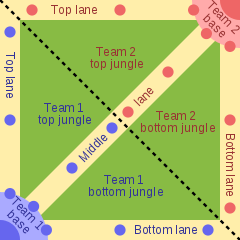

Each match starts with two opposing teams, typically made up of five players. Players work together as a team to achieve the ultimate victory condition which is to destroy their enemy's base[6] though some games have the option of different victory conditions.[7] Usually, each team has main structure which must be protected until opposing team's is destroyed, preventing enemy team from doing the same. The first team to destroy the opposing team's main structure wins the match. Destroying other structures within the opposing team's base may confer other benefits. Defensive structures, which are usually automatic "towers", are in place to prevent this, as well as relatively weak computer-controlled units, called "minions", which periodically spawn in groups at the base and marching down predefined paths (called "lanes") toward the enemy base.[8] There are typically 3 "lanes" that are the main ways of getting from one base to another; in between the lanes is an uncharted area called the "jungle." The lanes are known as top, middle and bottom lane, or, in gamer shorthand – "top", "mid" and "bot".

A player controls a single powerful in-game unit, called "hero" or "champion", who comes with a diverse set of unique abilities. When a hero stands near a killed enemy unit or kills an enemy unit, they gain experience points and gold which allow the hero to level up and buy items at a store. When a hero levels up, they may strengthen one of their abilities which they typically have four of. If a hero runs out of health points and dies, he is removed from active play until a respawn timer counts down to zero, where he is then respawned in his base. Respawn time generally increases as hero levels up.[9]

Heroes typically fall into one of several roles, such as tank, damage dealer, healer, and support, each of which having a unique design, strengths, and weaknesses. Also typically, MOBA games offer a large number of viable playable heroes for the player to choose from – League of Legends, for instance, began with 40, and has added at least one new one every month for its entire lifespan, reaching 100 in 2012.[10] This adds to the learning curve of the game as players learn the game's goals and strategies. Choosing a character who complements player's teammates and counters his opponents, opens up a strategy before the beginning of the match itself. Players usually find at least one hero they excel at playing, and familiarize themselves with the remaining roster. Additionally, each hero is deliberately limited in the roles they can fulfill. No one hero is ever (supposed to be) powerful enough to win the game without support from their team. This creates a strong emphasis on teamwork and cooperation.

Each player typically receives a small amount of gold per second during the course of the game. Moderate amounts of gold are rewarded for killing hostile computer-controlled units and larger amounts are rewarded for killing enemy heroes. Gold is used by heroes to buy a variety of different items that range in price and impact. For the most part, this involves improving the combat viability of the hero, although there may be other items that support the hero or team as a whole in different ways.[11]

As the heroes of each team get stronger, they can use multiple strategies to gain an advantage. These strategies can include securing objectives, killing enemy heroes and farming gold by killing computer-controlled units. The stronger a team gets, the more capable they are at destroying the enemy team and their base.

Character classes and roles

In most MOBAs, playable characters have assigned classes such as "tank", "marksman", "mage", "fighter", "assassin", "support" and "healer". During the match, they can be played as "carry", "support" and "ganker"; however the number and type of roles can differ depending on the game.[12][13] The carry role is expected to scale and itemize themselves to do the most damage against enemy characters and objectives, but may also require protection and assistance from their team members.[12] Supports are characters who support the entire team with abilities that are meant to aid allies and disable or slightly harm enemies. Some supports have healing abilities which can be vital factor in your team composition’s success, giving health and sustain to an ally while limiting enemy's options in terms of play patterns.[14] Ganker roles are flexible, as they have both carry and support skills that are used to disrupt and eliminate enemies, thus giving their teammates an advantage over their opponents.[12] Gankers can "act as a strategist, decision-maker or supporter depending on the team's needs."[12] Player roles can also be classified by the particular lane they are focusing on, such as "top laner", "mid laner", and "bottom laner",[15] or by their role in a teamfight, such as "frontliner", "damage dealer", "healer", "flex", and the "offlaner".[14]

Resemblance to other genres

As a fusion of real-time strategy, role-playing, and action games, members of the genre have lost many traditional RTS elements. This type of games moved away from constructing additional structures, base management, army building, and controlling additional units. Map and the main structures for each team are still present, and destroying enemy main structure will secure victory as the ultimate victory condition. Players can find various friendly and enemy units on the map at any given time assisting each team, however these units are computer-controlled and players usually don't have direct control over their movement and creation; instead, they march forward along set paths. Unlike in real-time strategy games (RTS), player has control over the only one single unit, called hero or champion. However, some MOBA games have certain heroes which control a few specialized units,[16] but not on a massive scale which is typical for RTS.

The MOBA genre resembles role-playing games (RPG) in gameplay, though the MOBA genre focuses on the multiplayer battle in the arena-like environment, while RPG as genre typically revolve around single player story and its chapters, and exploration of different locations. A key features, such as control over one character in a party, growth in power over the course of match, learning new thematic abilities, using of mana, leveling and accumulation of experience points,[17] equipment and inventory management,[18] completing quests,[19] and fighting with the stationary boss monsters,[20][21] have resemblance with role-playing games.

History

Origins

The roots of the genre can be traced back decades to one of the earliest real-time strategy titles, the 1989 Sega Mega Drive/Genesis game Herzog Zwei.[22][23] It has been cited as a precursor to,[24] or an early example of,[25] the MOBA genre. It used a similar formula, where each player controls a single command unit in one of two opposing sides on a battlefield.[22][23][24] Herzog Zwei's influence is also apparent in several later MOBA games such as Guilty Gear 2: Overture (2007)[26][27] and AirMech (2012).[25]

In 1998, Future Cop: LAPD featured a strategic Precinct Assault mode similar to Herzog Zwei, in which the players could actively fight alongside generated non-player units.[28][29] The PC version also allowed for online competitive play,[30] technically making Future Cop: LAPD the first MOBA game ever released as, unlike Herzog Zwei, it meets the criteria of an online battle arena.

Also in 1998, computer game company Blizzard Entertainment released its best-selling real-time strategy game (RTS) StarCraft with a suite of game editing tools called StarEdit. The tools allowed members of the public to design and create custom maps that allowed play that was different from the normal maps. A modder known as Aeon64 made a custom map named Aeon of Strife (AoS) that became popular.[3][31] Aeon64 stated that he was attempting to create gameplay similar to that of Future Cop: LAPD's Precinct Assault mode. In the Aeon of Strife map, players controlled a single powerful hero unit fighting amidst three lanes, though terrain outside these lanes was nearly vacant.[32]

Establishing the genre: 2000s

In 2002, Blizzard released Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos (WC3), with the accompanying Warcraft III World Editor. Both the multiplayer online battle arena and tower defense subgenres took substantive shape within the WC3 modding community. A modder named Eul began converting Aeon of Strife into the Warcraft III engine, calling the map Defense of the Ancients (DotA). Eul substantially improved the complexity of play from the original Aeon of Strife mod. Shortly after creating the custom DotA map, Eul left the modding scene. With no clear successor, Warcraft III modders created a variety of maps based on DotA and featuring different heroes. In 2003, after the release of Warcraft III: The Frozen Throne, a map creator named Meian[1] created a DotA variant closely modeled on Eul's map, but combining heroes from the many other versions of DotA that existed at the time. Called DotA: Allstars, it was inherited after a few months by a modder called Steve "Guinsoo" Feak, and under his guidance it became the dominant map of the genre. After more than a year of maintaining the DotA: Allstars map, with the impending release of an update that significantly changed the map layout, Guinsoo left the development to his adjutant Neichus in the year 2005.[1] After some weeks of development and some versions released, the latter turned over responsibility to a modder named IceFrog, who initiated large changes to the mechanics that deepened its complexity and capacity for innovative gameplay. The changes conducted by IceFrog were well-received and the number of users on the Dota: Allstars forum is thought to have peaked at over one million.[32] Defense of the Ancients (DotA) is largely attributed to being the most significant inspiration for the multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) video game genre in the years to come.[33]

Mainstream popularity: 2008–present

By 2008, the popularity of DotA had attracted commercial attention.[34] That year, The Casual Collective released Minions, a Flash web game.[35] Gas Powered Games also released the first stand-alone commercial title in the genre, Demigod (2009).[36][37] In late 2009, Riot Games' debut title, League of Legends initially designed by the one of the original creators of DotA Allstars, Steve Feak, was released.[38][39] Riot began to refer to the game's genre as a multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA).[40] Also in 2009, IceFrog, who had continued to develop DotA: Allstars, was hired by Valve, in order to design a sequel to the original map.[32]

In 2010, S2 Games released Heroes of Newerth, with a large portion of its gameplay and aesthetics based on DotA: Allstars.[41][42] The same year, Valve announced Dota 2 and subsequently secured the franchise's intellectual property rights,[43][44] after being contested by Riot Games for the DotA trademark.[45] In 2012, Activision Blizzard settled a trademark dispute with Valve over the usage of the DOTA trademark and announced their own standalone game, which was eventually named Heroes of the Storm.[46][47][48][49][50] Dota 2 was released in 2013, and was referred to by Valve as an "action real-time strategy" game.[40] In 2014, Hi-Rez Studios released Smite, a MOBA with a third-person perspective.[51] Heroes of the Storm was released in 2015, featuring numerous original heroes from Warcraft III and other Blizzard's franchises.[52][53] Blizzard adopted their own personal dictation for their game's genre with "hero brawler", citing its focus on action.[54]

Next-generation wave and market saturation

In recent years, numerous video game developers and publishers, following the success of League of Legends and Dota 2, tried to be part of the next-generation MOBA wave by putting their own twist in the genre,[55][56][57][58][59] releasing games such as Battlerite (2017), and AirMech (2018). However, not everyone succeeded. After years of development, many games which were supported by "big-name" publishers have never been officially released or their servers were shut down shortly after release. The most notable examples are Dawngate (2015)[lower-alpha 3] by Electronic Arts,[60] DC Comics-based Infinite Crisis (2015) by Warner Bros.,[61] Arena of Fate (2016) by Crytek,[62] Gigantic (2017) by Perfect World Entertainment,[63] Master X Master (2018) by NCSoft,[64] and Paragon (2018) by Epic Games.[65]

During the 2010s, with the expansion of the smartphone market, numerous MOBA titles have been released for portable devices,[66] such as Vainglory (2014), and Arena of Valor[lower-alpha 4] (2016).

Impact

In the original DotA, each player controls only one powerful unit rather than a big army. While it still kept the large scale, core mechanics, and goals of the real-time strategy games, DotA attempted to avoid "clickfest" gameplay in which high actions per minute scores are mandatory for efficient playing, changing focus to the actual teamwork, coordination, and tactics. This made mod highly popular, as its dynamic and unpredictable fights, complex map, and hero-centric gameplay create a more competitive environment and opportunities for outplaying the enemy team.[68] By the early 2010s, multiplayer online battle arena has become a prominent genre in esports tournaments. In 2018 alone, the prize pools reached over 60 million dollars, which is about 40% of the total esports prize pools in the same year.[69] MOBAs are some of the most watched games in the world.[70] Major esports professional tournaments are held in venues that can hold tens of thousands of spectators and are streamed online to millions more.[71][72][73] A strong fanbase has opened up the opportunity for sponsorship and advertising, eventually leading the genre to become a global cultural phenomenon.[74]

A free-to-play business model, which is used by the biggest MOBA titles, have contributed to the genre's overall popularity. Players are able to download and play AAA-quality games at no cost. These games are generating revenue by selling cosmetic elements, including skins, voice lines, customized “mounts”, and announcers, but none of these give the functional gameplay advantages to the buyer. As of 2012, free-to-play MOBAs, such as League of Legends, Dota 2, Heroes of the Storm, and Smite were among the most popular PC games.[75] The success in the genre has helped convince many video game publishers to copy the free-to-play MOBA model.[76][77] SuperData Research reported that the genre generated over $2.5 billion of revenue in 2017.[78][79]

Similar to fighting games, MOBAs offer a large number of viable player characters for the player to choose from, each of which having different abilities, strengths, and weaknesses to make the game play style different. That means it's very likely that any player can find a hero who enables his specific multiplayer skills. Choosing a character who complements player's teammates and counters his opponents, opens up a strategy before the beginning of the match itself.[80] Playable characters blend a variety of fantasy tropes, such as high fantasy, dark fantasy, science fiction, sword and sorcery, Lovecraftian horror, cyberpunk and steampunk, featuring numerous references to popular culture and mythology.

Data analytics and match prediction

Due to the large volume of MOBA matches played on a daily basis globally,[lower-alpha 5] MOBA has become a platform to apply big data tools to predict match outcomes based on in-game factors such as hero kill/death/assist ratios, gold earned, time of a match, synergy with other players, team composition, and other parameters.[83][84] Artificial Intelligence playing in matches and predicting match outcomes is being researched.[85] Open AI developed the Open AI Five which were first showcased at the Dota 2 World Championship, The International 2017, during a 1v1 demonstration.[86] Open AI returned to The International 2018 where the Open AI Five played in two games against professional players.[87]

Notes

- Also known as action real-time strategy or, more recently, as hero brawler and team brawler

- Paragon is a canceled third-person MOBA game which was never officially released. Free-To-Play access to its open beta started in February 2017

- The number in brackets represents the year of official servers shut down

- Arena of Valor (AoV) is an international adaptation of Honor of Kings (2015) for markets outside mainland China[67]

- League of Legends alone had a reported 100 million active monthly players worldwide in 2016[81] and an average of 27 million League of Legends games played per day reported in 2014[82]

References

- "Frequently Asked Questions". GetDota.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010.

- John Funk (2 September 2013). "MOBA, DOTA, ARTS: A brief introduction to gaming's biggest, most impenetrable genre". Polygon. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "History of DotA". Gosugamers.net. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "How Modding Made Warcraft III Immortal". Fanbyte. 25 March 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Amstrup, Johannes; ersen (15 September 2017). "Best Modern MOBA Games – LoL, Dota 2, HotS & Smite Compared". Pro Gamer Reviews. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "Heroes of Newerth – Charge!". Dedoimedo.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010.

- "The Crystal Scar | League of Legends". Dominion.leagueoflegends.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Leahy, Brian (13 October 2010). "Dota Explained and How You Can Play it Now". Shacknews.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010.

- "Basic Survival – Learn Dota". PlayDota.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- Augustine, Rob (3 July 2012). "Introducing League of Legends' 100th champion: Jayce, the Defender of Tomorrow". Archived from the original on 9 November 2016.

- Biessener, Adam (13 October 2010). "Valve's New Game Announced, Detailed: Dota 2". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- Gavrilova, Nuangjumnong (22 January 2016). "The Effects of Gameplay on Leadership Behaviors: An Empirical Study on Leadership Behaviors and Roles in Multiplayer Online Battle Arena Games". Transactions on Computational Science XXVI: Special Issue on Cyberworlds and Cybersecurity. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 9783662492475.

- Ng, Patrick; Nesbitt, Keith; Blackmore, Karen (5 February 2015). Sound Improves Player Performance in a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena Game. Artificial Life and Computational Intelligence. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer, Cham. pp. 166–174. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-14803-8_13. ISBN 9783319148021.

- "Understanding Roles in HotS – Articles – Dignitas". dignitas.gg. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Can 5v5 Transform Vainglory into a Major Player in Esports? – Dexerto.com – Esports & Gaming". dexerto.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "The Lost Vikings – Heroes of the Storm". us.battle.net. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "What you need to know about the experience in Dota 2 written by Artem Uarabei | Click-Storm". Click-Storm.com. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Items | League of Legends". na.leagueoflegends.com. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "The 5 Most Important Heroes of the Storm Objectives". EsportsTalk.com. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Roshan Dota 2 Guide". FirstBlood®. 17 October 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Heroes of the Storm: How to Fully Utilize Boss and Mercenary Camps – Articles – Dignitas". team-dignitas.net. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Greg Lockley (3 June 2014), MOBA: The story so far Archived 27 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, MCV

- Andrew Groen (7 March 2012), Ask GR Anything: What's a MOBA? Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, GamesRadar

- GameAxis Unwired, p. 52, December 2008, SPH Magazines, ISSN 0219-872X

- Brown, Fraser (15 January 2013). "Like Macross without the drama". Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Alex Kierkegaard (4 January 2008), "Guilty Gear 2 -Overture-", Insomnia

- "Review: Guilty Gear 2: Overture (Microsoft Xbox 360) – Diehard GameFAN". diehardgamefan.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- "Future Cop: LAPD". IGN. 14 December 1998. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Future Cop L.A.P.D. Review". Gamerevolution.com. 1 September 1998. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Future Cop: LAPD". Play Old PC Games. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Dean, Paul (16 August 2011). "The Story of DOTA". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Dimirti (22 July 2013). "Dota 2: A History Lesson". The Mittani. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Funk, John (2 September 2013). "MOBA, DOTA, ARTS: A brief introduction to gaming's biggest, most impenetrable genre". Polygon. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Nguyen, Thierry (1 September 2009). "Clash of The DOTAs". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- Psychotronic (30 November 2008). "Minions". jayisgames.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Lopez, Miguel (21 February 2008). "Demigod". Gamespy.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- Nemikan (21 September 2009). "DOTA reborn: Three games inspired by the legendary WC3 mod". Icrontic.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- Perez, Daniel (16 January 2009). "League of Legends Interview". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- Arirang (3 October 2009). "A Look at the Future of Dota and the AoS Genre". GameRiot.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- Nutt, Christian (29 August 2011). "The Valve Way: Gabe Newell And Erik Johnson Speak". Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Jackson, Leah (23 December 2010). "Looking Back at 2010: The Year in PC Games". g4tv.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- Wedel, Mark (24 June 2010). "Kalamazoo-made 'Heroes of Newerth' drawing huge online gaming crowd". Kalamazoo Gazette. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010.

- "Valve Announces Dota 2". Valve. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010.

- Totillo, Stephen (13 October 2010). "Valve's New Game Is Dota 2". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Josh Augustine (17 August 2010). "Riot Games' dev counter-files "DotA" trademark". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Blizzard DotA – BlizzCon 2010 – Matt Gotcher, StarCraft II Level Designer". YouTube.com. 23 October 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- Augustine, Josh (23 October 2010). "The first heroes in SC2's DOTA map". PCGamer. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010.

- Reilly, Jim (11 May 2012). "Valve, Blizzard Reach DOTA Trademark Agreement". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012.

- Bramblet, Matthew (1 August 2013). "Diablo III Announcement Coming at Gamescon – Activision Blizzard Q2 2013 earnings report details the Blizzard All-Star progress and 'Project Titan' revamp". Diablo Somepage. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Blizzard's Diablo/Starcraft/WoW Crossover Has a New Name". Kotaku. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "MOBA Title SMITE Has A Release Date, Coming This March".

- "Blizzard's Worlds Collide When Heroes of the Dorm Launches June 2 – Everyone's invited to join the battle for the Nexus when open beta testing begins on May 19". 20 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- "From Warcraft III to Heroes of the Storm, Talking Art and Blizzard's Long History with Samwise Didier - AusGamers.com". www.ausgamers.com. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Blizzard explains why it doesn't call Heroes of the Storm a MOBA". GameSpot. 9 November 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- "Battlerite Review: All the teamfights you'd ever want in a MOBA, minus the MOBA structure". AllGamers. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "Paragon preview: Epic Games re-energises the MOBA with classic shooter elements and unique twists". International Business Times UK. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Chalk, Andy (27 January 2016). "NCsoft announces Master X Master, a tag-team "action MOBA"". PC Gamer. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "IGN: Arena of Fate has the 20-minute time limit on each match, and it's all about scoring enough points before that timer runs out". IGN India. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "GameSpot: Gigantic is the new free fast-paced hero shooter MOBA". GameSpot. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "Dawngate shutting down in 90 days". Engadget. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Warner Bros. shutting down Infinite Crisis only 2 months after launch". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "'Crysis' Developer Crytek Shuts Down All But Two Studios". Player.One. 20 December 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- McWhertor, Michael (31 January 2018). "Gigantic gets final update, shutting down in July". Polygon. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "NCsoft will shut down Master X Master just months after launch". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Schreier, Jason. "After Fortnite's Massive Success, Epic Shuts Down Paragon". Kotaku. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Trends In Online Gaming In 2017 And Beyond". plarium.com. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Webster, Andrew (18 December 2017). "Tencent is bringing China's biggest game to the rest of the world". The Verge. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Crider, Michael. "Why Are MOBA Games like League of Legends So Popular?". How-To Geek. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Hurst, Taylor (12 February 2019). "Esports Prize Pools: $155.9M (2018)". Medium. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Most watched games on Twitch – SullyGnome". sullygnome.com. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- France-Presse, Agence (5 November 2017). "Video game warriors do battle before 40,000 fans in China". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Webb, Kevin. "More than 100 million people watched the 'League of Legends' World Championship, cementing its place as the most popular esport". Business Insider. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Boudreau, Ian (26 August 2019). "The International 2019 was Twitch's most-watched Dota 2 event ever". PC Gamer. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Pooley, Jack (16 July 2019). "10 Amazing Video Game Moments Created By Fans". WhatCulture.com. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Gaudiosi, John (11 July 2012). "Riot Games' League Of Legends Officially Becomes Most Played PC Game In The World". Forbes. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Drain, Brendan (3 July 2012). "The Soapbox: League of Legends is the new World of Warcraft". Joystiq. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Stapleton, Dan (June 1, 2012). "Valve: We Won't Charge for Dota 2 Heroes". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- "League of Legends Tops Free-to-Play Revenue Charts in 2017". GAMING. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Forde, Matthew; Writer, Staff. "Moonton's Mobile Legends crosses $500 million in gross revenue". pocketgamer.biz. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Crider, Michael (6 November 2017). "Why Are MOBA Games like League of Legends So Popular?". How-To Geek. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Number of players of selected eSports games worldwide as of August 2017 (in million)". Rift Herald. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- Sheer, Ian (January 27, 2014). "Player Tally for 'League of Legends' Surges". Wsj.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- Hodge, Victoria; Devlin, Sam; Sephton, Nick; Block, Florian; Drachen, Anders; Cowling, Peter (17 November 2017). "Win Prediction in Esports: Mixed-Rank Match Prediction in Multi-player Online Battle Arena Games". arXiv:1711.06498 [cs.AI].

- "LoL Tier List". 17 November 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- "OPENAI'S DOTA 2 DEFEAT IS STILL A WIN FOR ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE". 28 August 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Savov, Vlad (14 August 2017). "My favorite game has been invaded by killer AI bots and Elon Musk hype". The Verge. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- at 07:04, Katyanna Quach 24 Aug 2018. "Game over, machines: Humans defeat OpenAI bots once again at video games Olympics". www.theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

External links