Mount Tremper

Mount Tremper, officially known as Tremper Mountain and originally called Timothyberg, is one of the Catskill Mountains in the U.S. state of New York. It is located near the hamlet of Phoenicia, in the valley of Esopus Creek.

| Mount Tremper | |

|---|---|

| Timothyberg, Tremper Mountain | |

Mount Tremper from Route 28 to southeast | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,740 ft (840 m) [1] |

| Prominence | 300 ft (91 m) |

| Coordinates | 42°4′27″N 74°16′39″W [1] |

| Geography | |

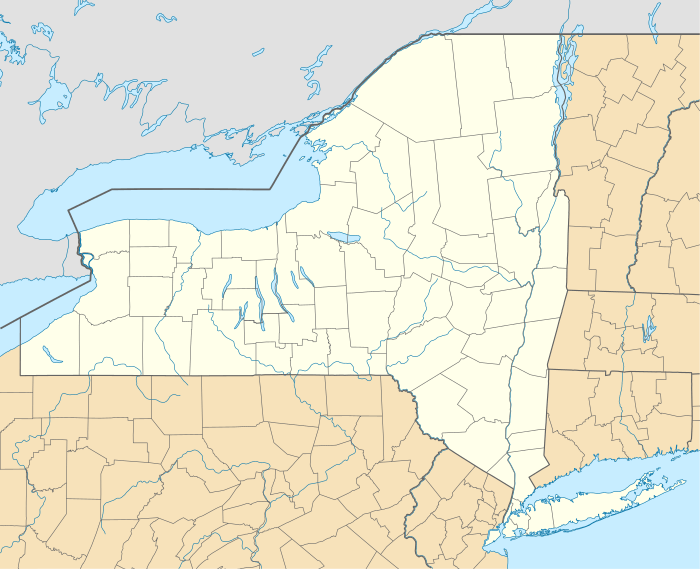

Mount Tremper Location of Mount Tremper within New York  Mount Tremper Mount Tremper (the United States) | |

| Location | Shandaken, New York, United States |

| Parent range | Catskills |

| Topo map | Phoenicia |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Trail/road |

At 2,740 feet (840 m) in elevation, it is well below the higher peaks of the region. Its slopes were a source of two major local products during the 19th century: hemlock bark, a source of tannin, and bluestone used in construction. Later it was the site of Tremper House, one of the Catskills' earliest railroad resorts. Henry Ward Beecher and Oscar Wilde were among the guests there.

In the 20th century it was acquired by the state and became part of the Catskill Park Forest Preserve. Its location in the Esopus Valley between the northern and southern Catskills made it an ideal place for a fire lookout tower, which still stands on the mountain's summit. The Mount Tremper Fire Observation Station has been restored and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Hikers often follow[2] the old road to it from Phoenicia, also a section of the Long Path long-distance trail, to enjoy the views from the tower.

Geography

Tremper is a sprawling mountain at the south end of a range of low-elevation peaks between Warners Creek and Silver Hollow on the north, Stony Clove Creek on the west, Esopus Creek on the southwest and the Beaver Kill on the southeast. The latter three are closely paralleled by state highways 214, 28 and 212. Its summit dominates the view from westbound Route 28 at the small hamlet of Mount Tremper.[1]

The mountain's lower slopes are gentle, becoming steep around 2,200 feet (670 m) and then leveling off again at the summit ridge. Unnamed tributaries of the surrounding creeks run down narrow valleys on the mountain's slopes. The summit ridge continues northeast to an unnamed summit and then Carl Mountain, both higher than Tremper at 2,820 feet (860 m) and 2,880 feet (880 m) respectively.[1]

Most of the mountain is within the Town of Shandaken, whose largest population center, the hamlet of Phoenicia, is at the southwest foot of the mountain. Another smaller settlement named after the mountain is to its south. A small portion of the mountain's lowest eastern slopes is within Woodstock.[1] Most of the land on the mountain is part of the Phoenicia Wild Forest management unit of New York's Forest Preserve, part of the Catskill Park. The rest, including most of the slower slopes, is privately owned.[3] The public land is managed by the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).[4]

Geology

Like the Catskills as a whole, a dissected plateau, Tremper was formed not through the upthrust of rock layers but by the gradual erosion of stream valleys in an uplifted region about 350 mya. Its rock layers and bedrock are primarily Devonian and Silurian shale and sandstone.[5] Bluestone is present in enough quantity that a quarry was once located on the south side of the mountain at an elevation of 1,495 feet (456 m). Its remains are still visible today from the old road to the fire tower, which passes it.[6]

Flora and fauna

Because of its low elevation, the forests on Mount Tremper are dominated by a forest type referred to in the Catskills as southern hardwoods.[7] This is dominated by oak, hickory and pine species, with some basswood and poplar scattered in lower elevations. Chestnut were once common as well, but most died off in the blight of the early 20th century. Some eastern hemlocks, once more widespread before they were harvested for their tannin-rich bark, remain, primarily higher on the mountain where the barkpeelers never reached. The summit ridge has some areas of the northern hardwood forest (beech, birch and maple) more common on higher Catskill slopes.[6] The more shade-tolerant northern hardwoods are slowly invading the southern hardwoods as an understory; due to the cessation of human intervention in the forest they will eventually displace the southern hardwoods.[7]

Tremper has a typical assortment of animal life for the Catskills. Herbivores such as white-tailed deer, chipmunks and porcupines dominate the lower end of the food chain, with predators like fishers and black bear at the top. The ledges in the former quarry are one of the few rattlesnake habitats in the Catskills close to a hiking trail, with at least one confirmed den,[8] and visitors should exercise caution if they wish to explore it.[2][9]

History

Tremper's human history has two stages. For the century after the area's first settlement it was primarily an economic resource, sustaining several industries. Since the end of that period it has become a recreational resource.

1780–1900: Barkpeeling, quarrying and hotels

The mountain was first known as Timothyberg, in the vernacular of the early Dutch settlers of the Catskills. The area was first settled in the 1780s. Its location near the creeks and valleys made it ideal for barkpeeling, the first major industry of the Catskills. Bark from the many eastern hemlocks on its slopes was a rich source of tannin, and leather hides were often brought to the region to be tanned. The creek valley made it possible to easily transport them to and from the Hudson River at Kingston to the east, and the later development of the Ulster and Delaware Railroad (UDRR) made it even easier. The road up the south side of the mountain, which forest historian Michael Kudish calls the best example of an extant bark road in the Catskills, was built for this purpose. By the end of the century, since a synthetic process for creating tannin had made it less necessary to harvest large acres of forest, it was being used for quarrying instead.[6]

The railroad made another industry possible at that time. In 1879, after hotelier Jacob Tremper opened the Tremper House, a resort on its slopes near Phoenicia, that part of the mountain became known by his name,[10] He invited a number of prominent clergymen of the time to its dedication. Henry Ward Beecher, the main speaker, asked for God's blessing on the location and predicted a prosperous future.[11] Another celebrity guest, Oscar Wilde, shocked the region during a lecture at the Tremper House in 1882 when he proclaimed its location at the foot of the mountain aesthetically preferable to those of hotels such as the Catskill Mountain House located on mountaintops since in valleys, "there the picturesque and beautiful is ever before you".[12]

It remained in business until 1904, when the town, under pressure from UDRR magnate Samuel Coykendall, who owned several competing resorts, rescinded permission for it to become a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients. Coykendall, and other hoteliers in the region, alleged that tourists would avoid the region if those patients were present anywhere within it.[13] The vacant hotel burned down four years later, in 1908, and was never rebuilt.[6]

A decade earlier, the legislation that created the state's Forest Preserve, with its "forever wild" clause, had been added to the state constitution. The state acquired Tremper's summit and some of the other land on its eastern slope in 1901, and established a plantation there for reforestation.[10] A mix of eastern white pine, Norway spruce and Scots pine were planted. Unusually for the Catskills, the underlying land was not former pasture but forest that had been cut and burned repeatedly by barkpeelers. It did not establish itself although the land eventually reforested on its own.[6]

1900–present: Hiking destination

The Timothyberg side of the mountain was regularly burned over by blueberry pickers every year through 1916, the year the state built the 47-foot (14 m) fire lookout tower on the mountain and extended the old board road to make it accessible for observers coming by vehicle. It replaced another tower that had briefly stood on Slide Mountain, the Catskills' highest peak, a few years earlier. Tremper was chosen since it offered views of the lowlands that could not be seen so easily from the fire towers on Hunter and Belleayre mountains.[14]

In 1921 the state bought more of the mountain, allowing it to designate the road as a hiking trail. By 1931 it had been extended beyond the tower as a footpath, descending the northeast side of the mountain into Hoyt Hollow to Willow. Later in the 1930s a lean-to was built at the summit for backpackers to camp in.[6]

This trail system remained unchanged for most of the mid-20th century, save for the construction of a new lower section of trail and a trailhead about 0.3 mile (500 m) east of the foot of the road just outside Phoenicia. When the dormant idea of the Long Path was revived in the 1960s, the trail over Tremper was included. A wayward campfire led in 1966 to a wildfire that burned 10 acres (4 ha) just below the summit. Four years later the state closed the tower.[6]

In 1976 the state purchased some more land along the trail and built another lean-to at 2,100 feet (640 m), along the trail below the summit. The next year the tower's two support structures, the observer's cabin and a storage shed, were removed. These were the last significant changes to facilities on Tremper for two decades.[6]

At the end of the century interest in restoring and preserving the fire tower led to a local fundraising campaign after DEC proposed to remove it as a structure incompatible with the Forest Preserve.[15] It was reopened in spring 2001 and listed on the National Register in late 2001.[16] A new extension of the Long Path along the ridge past Carl Mountain to Plateau Mountain was opened that year as well.

Access

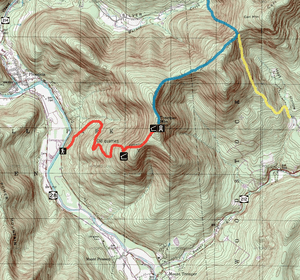

The Phoenicia Trail, part of the Long Path, the former bark road extended to the fire tower, is a widely used route to Tremper's summit. Blazed with red plastic DEC markers, it begins 1.6 miles (2.6 km) south of Phoenicia along Old Route 28 (now Ulster County Route 40), across from the Esopus. It joins the old road after a half-mile (1 km) and follows it through several switchbacks past the old quarry, a spring, the Baldwin Memorial Lean-To and another spring. It reaches the lean-to and fire tower at 2.8 miles (4.5 km), after climbing nearly 2,000 vertical feet (610 m) from the trailhead.[3][8][9]

Less used is the approach from the northeast via the Willow Trail. Its yellow markers begin at the intersection of Jessup and Silver Hollow roads in Willow. It follows Jessup for a mile (1.6 km) before turning into the woods and ascending the south wall of Hoyt Hollow 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to its end at the blue-blazed Warners Creek Trail (also the Long Path). From there the summit and fire tower are 2.2 miles (3.5 km) to the south. This route requires less vertical ascent (1,640 feet (500 m)) but is longer (3.8 miles (6.1 km)). Hikers sometimes park cars at both Willow and Phoenicia to do a 7-mile (10.2 km) shuttle hike across the mountain.[17]

The Warners Creek Trail also makes a long approach possible from Stony Clove Notch to the north. It is 7.6 miles (12.2 km) from the parking area on Route 214 to Tremper's summit, with the trail going over one mountain and up the north slope of Tremper from Warners Creek.[18]

See also

- List of mountains in New York

References

- Phoenicia Quadrangle – New York – Ulster Co (Map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic). United States Geological Survey. 1997. ISBN 0-607-94760-8. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- Adams 1990, p. 316.

- Northeastern Catskill Trails (Map) (8th ed.). 1:63,360. Cartography by Koch, Ted and Benjamin, Sheryl. New York – New Jersey Trail Conference. 2005. § 5L. ISBN 1-880775-46-8.

- "Lower Hudson Valley - Region 3". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- Titus 1993, pp. 22–34.

- Kudish 2000, pp. 144–148.

- Kudish 2000, pp. 34–43.

- Kick 2006, pp. 168–171.

- Chazin 2000, pp. 237–238.

- Annual report, Issue 7. Albany, New York: New York State Forest, Fish and Game Commission. 1902. p. 54. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- Evers 1972, p. 484.

- Evers 1972, p. 511.

- Evers 1972, p. 675.

- Podskosch 2000, p. 59.

- Herring, Hubert (November 5, 2000). "Phoenicia Journal; Great Views, and a Peek Into the Past". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- "National Register of Historic Places listings October 5, 2001". National Park Service. October 5, 2001. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- White & White 2002, pp. 96–97.

- Chong, Herb, ed. (2002). The Long Path Guide. Mahwah, NJ: New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. ISBN 1-880775-31-X.

Bibliography

- Adams, Arthur (1990). The Catskills: An Illustrated Historical Guide With Gazetteer. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-8232-1301-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chazin, Daniel (2000). New York Walk Book. Mahwah, NJ: New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. ISBN 1880775301.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evers, Alf (1972). The Catskills: From Wilderness to Woodstock. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-162-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kick, Peter (2006). AMC's Best Day Hikes in the Catskills & Hudson Valley. Boston, MA: Appalachian Mountain Club. ISBN 1-929173-84-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kudish, Michael (2000). The Catskill Forest: A History. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-02-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Podskosch, Martin (2000). Fire Towers of the Catskills: Their History and Lore. Fleischmanns, New York: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-10-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Titus, Robert (1993). The Catskills: A Geological Guide. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 0-935796-40-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Carol; White, David (2002). Catskill Day Hikes for All Seasons. Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club. ISBN 0-935272-54-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)