Mooring

A mooring is any permanent structure to which a vessel may be secured. Examples include quays, wharfs, jetties, piers, anchor buoys, and mooring buoys. A ship is secured to a mooring to forestall free movement of the ship on the water. An anchor mooring fixes a vessel's position relative to a point on the bottom of a waterway without connecting the vessel to shore. As a verb, mooring refers to the act of attaching a vessel to a mooring.[1]

The term likely stems from the Dutch verb meren (to moor), used in English since the end of the 15th century.

Permanent anchor mooring

These moorings are used instead of temporary anchors because they have considerably more holding power, cause less damage to the marine environment, and are convenient. Where there is a row of moorings they are termed a tier.[2] They are also occasionally used to hold floating docks in place. There are several kinds of moorings:

Swing moorings

Swing moorings also known as simple or single-point moorings, are the simplest and most common kind of mooring. A swing mooring consists of a single anchor at the bottom of a waterway with a rode (a rope, cable, or chain) running to a float on the surface. The float allows a vessel to find the rode and connect to the anchor. These anchors are known as swing moorings because a vessel attached to this kind of mooring swings in a circle when the direction of wind or tide changes.

For a small boat (e.g. 22' / 6.7 m sailing yacht), this might consist of a heavy weight on the seabed, a 12 mm or 14 mm rising chain attached to the "anchor", and a bridle made from 20 mm nylon rope, steel cable, or a 16 mm combination steel wire material. The heavy weight (anchor) should be a dense material. Old rail wagon wheels are used in some places (e.g. Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland) for this purpose. In some harbours (e.g. Dun Laoghaire, Ireland), very heavy chain (e.g. old ship anchor chain) may be placed in a grid pattern on the sea bed to ensure orderly positioning of moorings. Ropes (particularly for marker buoys and messenger lines) should be "non floating" to reduce likelihood of a boat's prop being fouled by one.

Pile moorings

Pile moorings are poles driven into the bottom of the waterway with their tops above the water. Vessels then tie mooring lines to two or four piles to fix their position between those piles. Pile moorings are common in New Zealand but rare elsewhere.

While many mooring buoys are privately owned, some are available for public use. For example, on the Great Barrier Reef off the Australian coast, a vast number of public moorings are set out in popular areas where boats can moor. This is to avoid the massive damage that would be caused by many vessels anchoring.

There are four basic types of permanent anchors used in moorings:[3]

- Dead weights are the simplest type of anchor. They are generally made as a large concrete block with a rode attached which resists movement with sheer weight; and, to a small degree, by settling into the substrate. In New Zealand old railway wheels are sometimes used. The advantages are that they are simple and cheap. A dead weight mooring that drags in a storm still holds well in its new position. Such moorings are better suited to rocky bottoms where other mooring systems do not hold well. The disadvantages are that they are heavy, bulky, and awkward.

- Mushroom anchors are the most common anchors and work best for softer seabeds such as mud, sand, or silt. They are shaped like an upside-down mushroom which can be easily buried in mud or silt. The advantage is that it has up to ten times the holding-power-to-weight ratio compared to a dead weight mooring; disadvantages include high cost, limited success on rocky or pebbly substrates, and the long time it takes to reach full holding capacity.[4]

- Pyramid anchors are pyramid-shaped anchors, also known as Dor-Mor anchors. They work in the upside-down position with the apex pointing down at the bottom such that when they are deployed, the weight of wider base pushes the pyramid down digging into the floor. As the anchors are encountered with lateral pulls, the side edges or corners of the pyramids will dig deeper under the floor, making them more stable.[5][6]

- Screw-in moorings are a modern method. The anchor in a screw-in mooring is a shaft with wide blades spiraling around it so that it can be screwed into the substrate. The advantages include high holding-power-to-weight ratio and small size (and thus relative cheapness). The disadvantage is that a diver is usually needed to install, inspect, and maintain these moorings.

- Multiple anchor mooring systems use two or more (often three) light weight temporary-style anchors set in an equilateral arrangement and all chained to a common center from which a conventional rode extends to a mooring buoy. The advantages are minimized mass, ease of deployment, high holding-power-to-weight ratio, and availability of temporary-style anchors.

Mooring to a shore fixture

A vessel can be made fast to any variety of shore fixtures from trees and rocks to specially constructed areas such as piers and quays. The word pier is used in the following explanation in a generic sense.

Mooring is often accomplished using thick ropes called mooring lines or hawsers. The lines are fixed to deck fittings on the vessel at one end and to fittings such as bollards, rings, and cleats on the other end.

Mooring requires cooperation between people on a pier and on a vessel. Heavy mooring lines are often passed from larger vessels to people on a mooring by smaller, weighted heaving lines. Once a mooring line is attached to a bollard, it is pulled tight. Large ships generally tighten their mooring lines using heavy machinery called mooring winches or capstans.

The heaviest cargo ships may require more than a dozen mooring lines. Small vessels can generally be moored by four to six mooring lines.

Mooring lines are usually made from manila rope or a synthetic material such as nylon. Nylon is easy to work with and lasts for years, but it is highly elastic. This elasticity has advantages and disadvantages. The main advantage is that during an event, such as a high wind or the close passing of another ship, stress can be spread across several lines. However, should a highly stressed nylon line break, it may part catastrophically, causing snapback, which can fatally injure bystanders. The effect of snapback is analogous to stretching a rubber band to its breaking point between your hands and then suffering a stinging blow from its suddenly flexing broken ends. Such a blow from a heavy mooring line carries much more force and can inflict severe injuries or even sever limbs. Mooring lines made from materials such as Dyneema and Kevlar have much less elasticity and are therefore much safer to use. However, such lines do not float on water and they do tend to sink. In addition, they are relatively more expensive than other sorts of line.

Some ships use wire rope for one or more of their mooring lines. Wire rope is hard to handle and maintain. There is also risk associated with using wire rope on a ship's stern in the vicinity of its propeller.

Mooring lines and hawsers may also be made by combining wire rope and synthetic line. Such lines are more elastic and easier to handle than wire rope, but they are not as elastic as pure synthetic line. Special safety precautions must be followed when constructing a combination mooring line.

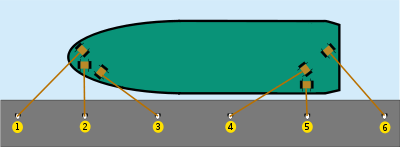

| ||

| Number | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Head line | Keep forward part of the ship against the dock |

| 2 | Forward Breast Line | Keep close to pier |

| 3 | Forward or Head Spring[7] | Prevent forward movement |

| 4 | Back or Aft Spring[7] | Prevent back movement |

| 5 | Aft Breast line | Keep close to pier |

| 6 | Stern line | Prevent forwards movement |

The two-headed mooring bitts is a fitting often-used in mooring. The rope is hauled over the bitt, pulling the vessel toward the bitt. In the second step, the rope is tied to the bitt, as shown. This tie can be put and released very quickly. In quiet conditions, such as on a lake, one person can moor a 260-tonne ship in just a few minutes.

Quick release mooring hooks provide an alternative method of securing the rope to the quay: such a system "greatly reduces the need for port staff to handle heavy mooring ropes … means staff have to spend less time on exposed areas of the dock, and [reduces] the risk of back injuries from heavy lifting".[8] The Oil Companies International Marine Forum recommend the use of such hooks in oil and gas terminals.[9]

The basic rode system is a line, cable, or chain several times longer than the depth of the water running from the anchor to the mooring buoy, the longer the rode is the shallower the angle of force on the anchor (it has more scope). A shallower scope means more of the force is pulling horizontally so that ploughing into the substrate adds holding power but also increases the swinging circle of each mooring, so lowering the density of any given mooring field. By adding weight to the bottom of the rode, such as the use of a length of heavy chain, the angle of force can be dropped further. Unfortunately, this scrapes up the substrate in a circular area around the anchor. A buoy can be added along the lower portion of rode to hold it off the bottom and avoid this issue.

Other types

Non-line mooring ("hands-free") is used where pier time is highly valuable, and includes suction cups[10][11][12] or magnets.[13][14] It can also be used between ships.[15]

Mediterranean mooring

_anchored_at_Naval_Support_Activity_La_Maddalena%2C_Italy%2C_on_1_September_1983_(6369543).jpg)

Mediterranean mooring, also known as "med mooring" or "Tahitian mooring", is a technique for mooring a vessel to pier. In a Mediterranean mooring the vessel sets a temporary anchor off the pier and then approaches the pier at a perpendicular angle. The vessel then runs two lines to the pier. Alternatively, simple moorings may be placed off the pier and vessels may tie to these instead of setting a temporary anchor. The advantage of Mediterranean mooring is that many more vessels can be connected to a fixed length of pier as they occupy only their width of pier rather than their length. The disadvantages of Mediterranean mooring are that it is more likely to result in collisions and that it is not practical in deep water or in regions with large tides.

Travelling mooring / Running mooring

A mooring used to secure a small boat (capable of being beached) at sea so that it is accessible at all tides. Making a Travelling Mooring involves (1) the sinking of a heavy weight to which a block (pulley wheel) is attached at a place where the sea is sufficiently deep at low tide, (2) fitting a block / pulley wheel to a rock or secure point above the high tide mark, and (3) running a heavy rope with marker buoy between these blocks.

Mooring involves (a) beaching the boat, (b) drawing in the mooring point on the line (where the marker buoy is located), (c) attaching to the mooring line to the boat, and (d) then pulling the boat out and away from the beach so that it can be accessed at all tides.

Canal mooring

A mooring used to secure a Narrowboat (capable of traversing narrow UK canals and narrow locks) overnight, during off boat excursions or prolonged queuing for canal lock access. Water height with minimal exceptions, remain constant (not-tidal); there is water height variance in close proximity to locks.[16]

Types of canal moorings are

Mooring pin (boat operator supplied) driven into the ground between the edge of the canal and the Towpath with a mooring-line rope to the boat.[17]

Mooring hook (boat operator supplied) placed on the (permanent) canal-side rail with either (boat operator supplied) rope or chain-and-rope to the boat.[17]

Mooring ring (permanent) affixed between the edge of the canal and the tow path, with (boat operator supplied) rope to the boat.[17]

Mooring Bollard (permanent) affixed canal-side on lock-approaches for the short-term mooring of advancing boats and lock-side to assist in ascent and descent.[17]

Mooring line materials

- Sisal

- Hemp

- Steel wire

- Polyethylene

- Polypropylene

- Polyester (e.g., used for deepsea mooring of offshore platforms)

- Nylon

- Chain

- High-performance mooring lines

See also

- Anchor – Device used to connect a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting

- Anchorage (shipping)

- Berth (moorings) – Designated location in a port or harbour used for mooring vessels

- Mooring mast

- Sailing – Propulsion of a vehicle by wind power

References

- Maloney, Elbert S.; Charles Frederic Chapman (1996). Chapman Piloting, Seamanship & Small Boat Handling (62 ed.). Hearst Marine Books. ISBN 978-0-688-14892-8.

- "tier". Oxford English Dictionary. XVIII (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989. p. 74.

- "About Moorings". The Lake Life.

- Jamestown Distributors. "Mooring Basics – How to Install a Permanent Mooring". How Tos.

- Leonard, Beth A. (January 2014). "Everyday Moorings". Seaworthy. BoatUS Marine Insurance Program (January 2014). Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- US 5640920, issued 1997-06-24

- Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Volume 1 B.R.67(I)

- "Let's go! Six-figure investment made in port's berths". City of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "Quick release mooring hooks". James Fisher and Sons plc.

- "First inland vacuum-based mooring system installed on St. Lawrence Seaway locks". Professional Mariner. September 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Hands Free Mooring on YouTube

- Stensvold, Tore (30 October 2015). "Nå skal de suge fast skipene til kaia". Teknisk Ukeblad. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/111541/Himanen_Laura.pdf?sequence=1

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 2017-03-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Intelligent Ship to Ship Mooring". Delft University of Technology. 1 January 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Boater's Handbook" (PDF). Canal & River Trust. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Banksides and Mooring". French Waterways. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mooring (watercraft). |

- IACS Unified Requirement A: Mooring and Anchoring

- Find moorings

- "Docking The World's Great Liners" Popular Mechanics, May 1930, article on docking large ships in the first half of the 20th century

- ShipServ Pages Mooring Ropes

- Video on Canal Mooring

- Anchor Chain and Mooring Fittings