Mooragh Internment Camp

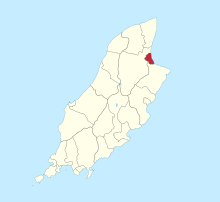

Mooragh Camp was a World War II internment camp in Ramsey, Isle of Man, in operation from May 1940 until September 1945. It was the first such camp on the island since World War I.

The opening of the camp

Following an announcement of the planned camp in the Manx newspapers in the second week of May 1940, official letters were sent out on 12 May to inform occupants of all the houses along the Mooragh Promenade that their houses were to be requisitioned to form a camp to intern enemy aliens. The residents had to be out of their houses by 18 May, and they were to leave behind all furniture, bedding, linen, cutlery, crockery and utensils.

Some thirty boarding houses and hotels along the Mooragh Promenade were requisitioned, as well as a number of bungalows nearby to be used for billeting the military guard. The camp also included the Mooragh golf links, which were to be used as a recreation ground for the internees.

The road leading from the swing bridge to the Mooragh Park was to remain open to the public, although part of the roadway was included within the compound. A double row of barbed wire fencing was erected as the perimeter of the camp. On the seaward side the fence extended to within a few feet of the sea wall, allowing a narrow alleyway for the use of the patrolling guards.[1]

On 26 May ten officers and 150 men belonging to the Royal Welch Fusiliers arrived at Ramsey on the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company ship, the Castle Rushen, ready to take up guard of the camp, under Captain Alexander.[2]

On the following day, Monday 27 May, the armed military force took up position guarding the length of Queen's Pier, ready to receive the first shipment of internees. 823 men arrived on the Belgian cross-Channel steamer Princess Josephine Charlotte, and they were despatched in batches to the base of the pier and assembled along the South Promenade. A large body of police from Douglas also assisted in the marshalling arrangement as large crowds of local people stood by to watch. The guards then accompanied the prisoners, some of them whistling, as they walked along the South Promenade and the quay before crossing over the swing bridge to the camp.[3]

The Courier later reported that:

"...it was seen that the aliens were mostly youthful or middle-aged. There were practically no elderly men among them. As they came ashore they carried with them their belongings in suitcases, attaché cases and bundles on their backs. They were a mixed lot: some well dressed and bearing signs of affluence, others were of lowlier mien and wore canvas shoes. One alien had his dog with him: another – somewhat optimistically – was carrying a fishing rod. Another carried a typewriter in his hand."[4]

Later changes

The camp changed over time, with new countries joining the war and a flow of releases of the internees who were deemed to pose no threat to the Allies.

In around April 1941 Mooragh Camp received an influx of internees from Peel as Peveril Camp was cleared to make ready for British fascists.[5]

In November 1942 180 Finns moved to the camp when the Palace Camp in Douglas closed.[6] The Finns were mainly sailors who had been captured, serving aboard Swedish cargo ships that had undergone inspections by the Royal Navy. Although many were pro-British, the majority were pro-Nazi, an imbalance which only increased with time as more pro-British internees were released.

By April 1943 the Finns made up a quarter of the camp’s total population, the rest being made up of Germans and Italians. The different nationalities were allocated houses in different sections of the promenade separated off by barbed wire. The sections were known as 'F' Camp for the Finns, 'L' Camp for the Germans and 'N' Camp for the Italians. It stayed in this format until the camp’s closure on 2 August 1945.[7]

Camp life

Each boarding house constituted an independent unit with its own internees taking up positions such as of leader, kitchen staff, cleaners, orderlies and cooks. There was one recreation room (the only one heated), a dining room, toilet, bathroom and the bedrooms. Each camp compound also had a group of boarding houses allocated for special purposes such as workshops for tailors, toy makers and watchmakers, professional activities which were first permitted shortly after the camp was formed. Another group of buildings featured a library which internees were free to use, as well as a canteen, wash-house, drying room and storehouses.[8]

After initial suspicion of the internees relaxed on the island, in both residents and the authorities alike, employment outside of the camps was permitted. This was chiefly as farm labour, helping to fill a shortfall by 1943 of almost 800 men brought about by local call-ups to the military.[9]

The camp was exceptional on the island for having free access to news from the camp’s opening, with 36 copies of the Daily Mail and of the Ramsey Courier being made available daily.[10]

Like other camps on the island, Mooragh published a camp newspaper, the Mooragh Times, in which were published poems and other pieces written by internees in both German and English. In addition to this there was published a booklet entitled Stimmen hinter Stracheldraht, or "Voices behind Barbed Wire", a collection of works from internees within Mooragh and from other camps on the island.[11] Amongst the pieces published was a poem, Mooragh, July 1940, by F. F. Beiber, which offers a picture of the mood of many internees in Mooragh:

Beyond barbed wire

The sea,

And the sun’s last fire

Burning up a tree

And a cottage on the green hill.

Gulls idle on the beach,

Then rise into the air and cry.

The field across the bay we cannot reach,

We can but pace our cage and let our hungry eye

Take in far loveliness which will

Remain

Beyond our sadness and beyond despair,

Beyond our stubborn hope, beyond our fair

And puzzled sense of justice. They will stand,

This bay, their pier, this beach, this sea,

This distant friendliness of wooded land -

To bid farewell to us when we are free.[12]

Attempted escapes and other disturbances

An escape from the camp was achieved at around 9.30 pm on Wednesday 15 October 1941 by three pro-Nazi Dutchmen, two ships' officers from the mercantile marine and a civil air pilot. Having been planning the escape for two months, in which time they had studied the movements of the guards and built a ladder to get over the fence, they were forced to carry out the escape quickly and in terrible weather conditions as they had discovered that they were to be transferred to Peveril Camp in Peel the following day. Having previously studied the harbour on their official walks, they quickly found a dinghy and paddled out to the yacht Irene. Despite having been immobilised, as required by war regulations, the men were able to steer the yacht out of the harbour on the ebb tide and then put up the sails when beyond the harbour. Their intention was to sail to Ireland, but this was near to impossible in the weather conditions, a south-westerly Force 10 gale. Once their absence was spotted, an extensive search was carried out on land, at sea and by air. The yacht was spotted by the RAF and monitored without any attempt being made to board her. The yacht finally landed at a creek near Eskmeels, south of St Bees Head, Cumberland, some time around midnight, having been driven hopelessly off course during the storm. The three men were arrested by the military and held in Whitehaven until the next morning when a party of Manx police arrived on the first boat into Fleetwood. As was the norm for such cases, the men returned to the Isle of Man to face civil trial for the theft of the boat, valued at £300. They were each sentenced to six-month prison sentences, which were spent in the island's prison. Upon their release they were returned to internment, this time at Peveril camp.[13]

By the start of 1943 there were a large number of Finns in the camp, many of whom were of a sort that was "often homeless, semi-literate and semi-vagabond."[14] Their section of the camp had become a rough and dangerous place where violence often broke out. This was not helped by their strengthening the alcohol allowed to them by adding the likes of hair oil, boot-blacking and wood polish to it. The raucous and dangerous activities of the camp increased around the date of Hitler's birthday on 20 April, at which point the canteen was looted of all of its alcohol; this only increased the drunkenness and violence. On the morning of 20 April a 26-year-old Finnish man carried a bucket of dirty water from his own house over to the house next door, where he threw it over the face of a man who had been standing there by the entrance to the house. After a moment of shock this 36-year-old man pulled a knife from his pocket and stabbed the younger man in the chest. The knife penetrated the man's heart, and he died moments later, having staggered back to fall on the pavement outside his own house. A mob then formed which proceeded to severely beat the older man, but he escaped serious harm by running out into the protection of the guards when they opened the gates in order to enter to stem the disturbance. In the civil trial that followed, the man was found not guilty of both murder and manslaughter: it was held that his life was in danger and so the knifing was carried out in self-defence. The man was then returned to the camp.[15]

Mooragh Camp saw the final serious escape attempt made on the island during the war. A 28-year-old and a 32-year-old German had identified a section of the perimeter fence where the wire was simply looped round a boundary post and twisted together. On Sunday evening 11 March 1945 they untwisted the wire and made a gap wide enough to slip through. Unique amongst escapes on the island, they took with them some food. This enabled them to sleep rough in the fields without having to come into contact with anyone. After a week of cold and wet weather, during which up to 300 people took part in searches for them, at 7.45 am on Monday 18 March they walked into Bride post office and gave themselves up to the sub-postmistress, the first official they came across. In later interrogation, they both admitted that they knew that they could not realistically hope ever to have got off the island.[16]

Significant internees

- Peter Gellhorn (1912–2004), conductor, composer, pianist and teacher

- Walter Joseph (1922–2003), photographer

- Rabbi Werner van der Zyl (1902–84), founder of Leo Baeck College

See also

- Category: People interned in the Isle of Man during World War II

Notes and references

- http://www.airfieldinformationexchange.org/ Archived 18 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Island of Barbed Wire, Connery Chappell, Corgi Books, London, p. 40

- Chappell, p. 42

- http://www.airfieldinformationexchange.org/ Archived 18 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Chappell, p.123

- Chappell, p.193

- Chappell, p.232

- http://www.airfieldinformationexchange.org/ Archived 18 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Records from June 1943 show the number of male farm workers down to 1,027 from a figure of 1,800 in 1940, recorded in Chappell, p.216

- Ramsey Police note of 4 June 1940, recorded in Chappell, p.78

- JPG images of Stimmen hinter Stracheldraht available on http://www.edwardvictor.com

- JPG image on http://www.edwardvictor.com

- Chappell, pp. 175–179

- Chappell, pp. 195

- Chappell, pp. 193–200

- Chappell, pp. 209–211