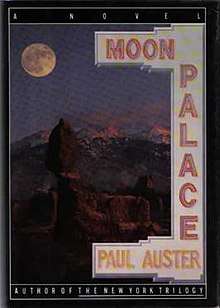

Moon Palace

Moon Palace is a novel written by Paul Auster that was first published in 1989.

First edition | |

| Author | Paul Auster |

|---|---|

| Country | USA |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Picaresque |

| Publisher | Viking Press |

Publication date | February 1989 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 320 pp |

| ISBN | 0-670-82509-3 |

| OCLC | 18415393 |

| 813/.54 19 | |

| LC Class | PS3551.U77 M66 1989 |

The novel is set in Manhattan and the U.S. Midwest, and centers on the life of the narrator Marco Stanley Fogg and the two previous generations of his family.

Plot summary

Marco Fogg is an orphan and his Uncle Victor his only caretaker. Fogg starts college, and nine months later moves from the dormitory into his own apartment furnished with 1492 books given to him by Uncle Victor. Uncle Victor dies before Fogg finishes college and leaves him without friends and family. Marco inherits some money which he uses to pay for Uncle Victor's funeral. He becomes an introvert, spends his time reading, and thinks, "Why should I get a job? I have enough to do living through the days." After selling the books one by one in order to survive Fogg loses his apartment and seeks shelter in Central Park. He meets Kitty Wu and begins a romance with her after he has been rescued from Central Park by Zimmer and Kitty Wu. Eventually he finds a job taking care of Thomas Effing.

Fogg learns about the complicated history of his parents, and Effings' previous identity as the painter Julian Barber. When Effing dies, leaving money to Fogg, Marco and Kitty Wu set up a house together in Chinatown. After an abortion Fogg breaks up with Kitty Wu and travels across the U.S. to search for himself. He begins his journey with his father Solomon Barber, who dies shortly after an accident at Westlawn Cemetery, where Fogg's mother is buried. Marco continues his journey alone, which ends on a lonely California beach: "This is where I start, ... this is where my life begins."

From Uncle Victor to Columbia University

Marco Stanley Fogg, aka M.S., is the son of Emily Fogg. He doesn't know his father. His mother dies because of a car accident when he is eleven years old. He moves to his Uncle Victor, who raises him until Marco goes to a boarding school in Chicago. When he reaches college age, he goes to Columbia University in New York City. After spending his freshman year in a college dormitory, he rents an apartment in New York.

Uncle Victor dies, which makes Marco lose track. After paying the funeral costs, Marco realizes that very little of the money that Uncle Victor gave him is left. He decides to let himself decay, to get out of touch with the world. He makes no effort to earn money. His electricity is cut off, he loses weight, and finally he is told that he must leave his apartment. The day before he is thrown out, Marco decides to ask Zimmer, an old college friend with whom he has lost contact, for help. Zimmer has moved to another apartment, so when Marco arrives at Zimmer's old apartment, he is invited by some strangers to join their breakfast. At that breakfast he meets Kitty Wu for the first time. She seems to fall in love with him. The next day, Marco has to leave his flat, and finds himself on the streets of Manhattan.

Central Park

Central Park becomes Marco's new home. Here he seeks shelter from the pressure of the Manhattan streets. He finds food in the garbage cans. Marco even manages to stay in touch with what is going on in the world by reading newspapers left by visitors. Although life in Central Park is not very comfortable, he feels at ease because he's enjoying his solitude and he restores the balance between his inner and outer self. This part devoted to Central Park may be considered an echo to the main themes of Transcendentalism and the works of Thoreau and Whitman.

At first, the weather is very good, so where to stay is not a big problem. But after a few weeks the weather changes. In a strong rain shower, Marco becomes ill and retires to a cave in Central Park. After some days of delirium, he crawls out of the cave and has wild hallucinations while lying outside. There, he is finally found by Zimmer and Kitty Wu, who have been looking for him for the whole time. Due to the fever he mistakes Kitty for an Indian and calls her Pocahontas.

At Zimmer's

Zimmer (the German word for room) is a good friend, hosts Marco in his apartment, bears all his expenses, and helps him to recover. But when Marco has to go to the army physical, he is still rated unfit because of his poor physical and mental state. Marco feels very bad about living at Zimmer's costs, so he finally persuades him to let him do a French translation for him to earn some money. Then he meets Kitty again, and decides to leave Zimmer. They lose touch, and when, after thirteen years, they happen to run into each other in a busy street, Marco learns that Zimmer has married and become a typical middle-class citizen.

At Effing's

After he has finished his work on the translation, Marco searches for another job offer. He finds a job at Effing's, where he is hired for reading books to Effing and driving the old, blind and disabled man through the city of New York in his wheelchair. Effing is a strange man who tries to teach Marco in his own way, taking nothing for granted. Marco has to describe to Effing all the things he can see while driving the old man around. This way, Marco learns to look at the things around him very precisely. Later, Effing tells Marco to do the main work he was hired for: write his obituary. Effing tells him the main facts of his life as the famous painter Julian Barber and his conversion to Thomas Effing. He went to Utah with Byrne, a topographer, and Scoresby, a guide, to paint the vast country. Byrne fell from a high place and the guide flees from the place, leaving Barber alone in the middle of the desert. Barber finds a cave where a hermit used to live and begins to live there. He kills the Gresham brothers, three bandits, and takes the money to San Francisco, where he officially takes the name "Thomas Effing". He becomes rich, but one day someone tells him he's very similar to Julian Barber, a famous painter who disappeared. He sinks in depression and fear and begins frequenting China Town, taking drugs, etc. But one day someone attacks him, rushes and hits a street lamp, becoming paraplegic. He stops having such an unhealthy life, and decides to go to France. He comes back to the US in 1939 fleeing from the Nazis.

Solomon Barber

Solomon Barber is Marco's father and Effing's son. He is extremely fat (which contrasts to Marco's period of starvation) and didn't know his father nor that he has a son. He inherits most of the fortune of Effing. He meets Marco after the death of Effing to learn about his father and finds a son. Marco, in the family cyclic pattern, doesn't know that Barber is his father. Barber had a relationship with one of his students, Emily, and never knew she was pregnant. Marco learns the truth when he sees Barber crying in front of Emily's grave.

Characters

Marco Stanley Fogg / M.S.

The name:

"Marco" refers to Marco Polo, the western explorer who reached China (Later M.S. "discovers" Kitty Wu and Uncle Victor gives him 1492 books, like the year of the discovery of "The New World" by Columbus).

"Stanley" refers to the reporter Henry Morton Stanley, who found Dr. David Livingstone in the heart of darkest Africa. This could be related to the fact that he finds or discovers his father and grandfather.

"Fogg" originally comes from Fogelmann (probably, deriving from German "Vogel" - "bird" and "Mann" - "man"), which was changed to Fog by the immigration department. The second "g" was added later. Marco says about his last name: "A bird flying through the fog, a giant bird flying across the ocean, not stopping until it reached America" (this resembles the American Dream).

"Fogg" refers to Phileas Fogg, the protagonist in the novel of Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days. "Around the World in Eighty Days" is also referred to in the book as Marco happens to see the 1956 movie adaption twice.

"M.S." Uncle Victor tells Marco "M.S." stands for manuscript, a book that is not yet finished (everybody is writing his own life, his own story). "MS" also refers to a disease: the multiple sclerosis. Marco quite appreciates this strangeness in his name.

Uncle Victor

Uncle Victor - the brother of Marco's mother - is a "spindly, beak-nosed bachelor" of forty-three who earns his living as a clarinetist. Although he lacks ambition, Uncle Victor must have been a good musician because for some time he is a member of the famous Cleveland Orchestra. Like all Foggs, he is characterized by a certain aimlessness in life. He does not settle down, but is constantly on the move. Because of a thoughtless joke, he has to leave the renowned Cleveland Orchestra. Then he plays in smaller combos: the Moonlight Moods and later the Moon Men. In order to earn a sufficient living, he also gives clarinet lessons to beginners. His last job is selling encyclopedias.

Uncle Victor is given to dreams, his mind restlessly shifting from one thing to another. He is interested in baseball and in all kinds of sport. His rich imagination and creativity allow him to invent playful activities for his nephew Marco. Uncle Victor carries out his guardianship for Marco in a responsible way, but he does not exercise adult authority over Marco. He forms a relationship based on sympathy, love and friendship. Marco loves his uncle's easy-going lifestyle, his humor and his generosity. Uncle Victor is also quite open-minded, likes movies and is fairly well-read, with 1492 books - a number obviously meant to remind us of the year when Columbus discovered America.

Thomas Effing / Julian Barber

Thomas Effing, father of Solomon and grandfather of Marco, was born as Julian Barber. He was a famous painter who lived in a house on a cliff. He was married to Elizabeth Wheeler, a young woman who, after the marriage, turned out to be frigid. Julian Barber eventually wanted to travel to the West and as his wife got scared he wouldn't come back, she spent one night with him. He undertook the expedition anyway and lived as a hermit in the desert for a little bit over a year. Since he never returned home to his pregnant wife, everybody thought that he was dead. He decided to be 'dead' and changed his name to Thomas Effing.

The first name Thomas was chosen by Julian Barber because he admired the painter Thomas Moran. The surname Effing echoes the inappropriate word f-ing (*fucking*). He adopted it to indicate that his whole life was "fucked up".

He started a new life as Thomas, and was then attacked which resulted in an accident that caused him to become paralyzed. He travels to Paris, where he stays until the beginning of the Second World War. Next he moves into a big New York apartment with his housemaid 'Mrs Hume' and his assistant Pavel Shum, a Russian student he met in Paris. Effing later learns that he has a son, an obese history professor, but never contacts him. After Pavel died in a car accident Effing employs Marco, his grandson, as his new assistant. Marco must read all kinds of books to him, describe the Manhattan scenery to the blind man while he takes him for walks in his wheelchair, and eventually has to write Effing's obituary.

Kitty Wu

Kitty is a girl with Chinese roots who falls in love with Marco and helps in searching for him during his central park period. This scene is a reference to the novel Around the World in Eighty Days, where the hero, Phileas Fogg, rescues an Indian woman from death; it can also be considered a reference to Pocahontas.

Like Marco she is an orphan as her parents had died when she was a child. After Effing's death they move together, having an impassionate relationship. But Marco leaves Kitty when she decides to have an abortion, and does not contact her until his father dies. But Kitty refuses to live with him again.

Symbols and motives

The quest for identities

Both Marco and Solomon are raised without having a father. This has a major impact on them:

- Marco completely loses orientation when Uncle Victor dies. He is very upset about not knowing his father. Throughout the novel, Marco tries to find his roots. Shortly after finding his father, he loses him again.

- Solomon writes a book that deals with the topic of a fatherless life at the age of seventeen, showing his own internal quest for identity. He does this by spending his nights composing it.

The moon

In this interview, published in The Red Notebook, Paul Auster looks at the meanings of the moon in Moon Palace:

The moon is many things all at once, a touchstone. It's the moon as myth, as ‘radiant Diana, image of all that is dark within us'; the imagination, love, madness. At the same time, it's the moon as object, as celestial body, as lifeless stone hovering in the sky. But it's also the longing for what is not, the unattainable, the human desire for transcendence. And yet it's history as well, particularly American history. First, there's Columbus, then there was the discovery of the west, then finally there is outer space: the moon as the last frontier. But Columbus had no idea that he'd discovered America. He thought he had sailed to India, to China. In some sense Moon Palace is the embodiment of that misconception, an attempt to think of America as China. But the moon is also repetition, the cyclical nature of human experience. There are three stories in the book, and each one is finally the same. Each generation repeats the mistakes of the previous generation. So it's also a critique of the notion of progress.[1]

A more prosaic explanation of the title is that the Moon Palace was a Chinese restaurant (now defunct) in the Morningside Heights neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, which was a popular student hangout when Auster was studying at Columbia University.

Similarities to author's life

Some aspects of the main character's life in Moon Palace mirror the life of the author. He was a descendant of an Austrian Jewish family, born on the Third of February 1947 in Newark, New Jersey, which is about 15 miles west of New York City. He also attended high school there. In his childhood, Auster's father Samuel Auster was often absent. Samuel Auster was a businessman who left the house in the morning before his son was awake and returned home when he was already in bed. Auster always searched for someone to replace his father. Unlike his father his mother gave Auster very much attention. In fact this may also put a different light on the title as the moon is symbolic of the female or the mother.

- Paul Auster and Marco Fogg were both born in 1947.

- Marco's, Solomon's and Paul's father were all absent during their sons' childhoods.

- When Paul's uncle travelled to Europe he stored several boxes of books at the Austers' home. Paul Auster read one book after the other. The same goes for Marco, who read his Uncle Victor's books.

- They both studied at Columbia University, New York.

- Both of them were involved in the student's demonstrations at Columbia University.

- Both Paul and Marco lost a lot of weight after running out of money.

- Effing and Paul went to France (Paris).

- Like Effing finds twenty thousand dollars in the saddlebag of the three gangsters he killed, Paul's son has stolen three thousand dollars out of the bag of a dead guy.

Adaptations

In 2009, Audible.com produced an audio version of Moon Palace, narrated by Joe Barrett, as part of its Modern Vanguard line of audiobooks.

Notes

- Source: Interview with Larry McCaffery and Sinda Gregory, The Red Notebook, Faber & Faber, Boston, 1995

References and further reading

- Addy, Andrew Narrating the Self: Story-Telling as Personal Myth-Making in Paul Auster’s Moon Palace. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 153–161.

- Auster, Paul Interview with Larry McCaffery and Sinda Gregory. In: Paul Auster. The Art of Hunger: Essays, Prefaces, Interviews and The Red Notebook. New York: Penguin Books, 1993, pp. 277–320.

- Bawer, Bruce Doubles and More Doubles. The New Criterion, 7:8 (April 1989), pp. 67–74.

- Becker, Peter von Marco Stanley Foggs Reise ins Ich. Süddeutsche Zeitung (05.12.1990), p. 7.

- Birkerts, Sven Postmodern Picaresque. The New Republic, 200:13 (March 27, 1989), pp. 36–40.

- Brooks, Carlo Désespoir et possibilité: le problème de l’appartenance au monde dans Moon Palace et Libra. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 163–175.

- Cesari Stricker, Florence Moon Palace ou les avatars du programm. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 177–182.

- Chassay, Jean-François Moon Palace: le palimpseste historique. In: Annick Duperray (ed.). L’oeuvre de Paul Auster: approaches et lectures plurielles. Actes du colloque Paul Auster. Aix-en-Provence: Actes Sud, 1995, pp. 215–227.

- Chauche, Catherine Approche phénoménologique de la représentation picturale dans Moon Palace de Paul Auster. Imaginaires: Revue du Centre de Recherche sur l’Imaginaire dans les Littératures de Langue Anglaise, 3 (1998), pp. 195–204.

- Chénetier, Marc Paul Auster as "the Wizard of Odds": Moon Palace. Didier Érudition CNED, 1996.

- Chénetier, Marc Around Moon Palace. A conversation with Paul Auster. Sources: Revue d’Études Anglophones, 1 (Fall 1996), pp. 5–35.

- Cochoy, Nathalie Moon Palace ou la formation du lecteur. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 183–192.

- Cochoy, Nathalie Prête-moi ta plume: la face cachée de New York dans la Trilogie et dans Moon Palace. In: Annick Duperray (ed.). L’oeuvre de Paul Auster: approaches et lectures plurielles. Actes du colloque Paul Auster. Aix-en-Provence: Actes Sud, 1995, pp. 228–241.

- Coe, Jonathan Moon Madness. Guardian (April 14, 1989), p. 30.

- Coulomb-Buffa, Chantal Réconciliation dans Moon Palace de Paul Auster. Revue Française d’Etudes Américaines, 62 (Nov. 1994), pp. 404–415.

- Cryer, Dan An Explorer on a Moonscape of the Mind. New York Newsday, 49:202 (March 26, 1989), p. 23.

- Delattre, Pierre A Wizardry of Transformations. Hungry Mind Review, 10 (Spring 1989), p. 16.

- Dirda, Michael Marvels and Mysteries. Washington Post Book World, 19:13 (March 26, 1989), p. 3.

- Dow, William Never Being ‚This Far from Home‘: Paul Auster and Picturing Moonlight Spaces. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 193–198.

- Eder, Richard He Wasn’t ‚Born‘ Until He Turned 22. Los Angeles Times, 108:117 (March 30, 1989), p. V21.

- Edwards, Thomas R. Sad Young Men. The New York Review of Books, 36:13 (August 17, 1989), pp. 52.

- Floch, Sylvain Ascetisme et austérité dans Moon Palace. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 199–207.

- Gébler, Carlos America’s Red Rock Soaked in Blood. Books, 3:1 (April 1989), p. 8.

- Gilbert, Matthew A Hypnotizing Tale from Paul Auster. Boston Globe, 235:89 (March 30, 1989), p. 78.

- Goldman, Steve Big Apple to the Core. The Guardian (April 18, 1989), p. 37.

- Goldstein, Bill A Spiritual Pilgrim Arrives in Grand Style. New York Newsday, 49:195 (March 19, 1989), p. 22.

- Gottlieb, Eli Moon Palace. Elle (March 1989), p. 208.

- Grim, Jessica Moon Palace. Library Journal, 114:2 (February 1, 1989), p. 81.

- Guilliatt, Richard Lunar Landscape. Time Out, 969 (March 15, 1989), Hardy, Mireille. Ceci n’est pas une lune: l’image-mirage de Moon Palace. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 209–215.

- Herzogenrath, Bernd ‘How can it be finished if my life isn’t?‘: The Picaresque. In: Bernd Herzogenrath. An Art of Desire: Reading Paul Auster. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999, pp. 115–124. pp. 29–30.

- Herzogenrath, Bernd Puns, Orphans, and Artists: Moon Palace. In: Bernd Herzogenrath. An Art of Desire: Reading Paul Auster. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999, pp. 125–156.

- Hoover, Paul The Symbols and Signs of Paul Auster. Chicago Tribune Books, 142:78 (March 19, 1989), p. 14/4.

- Indiana, Gary Pompous Circumstance. Village Voice, 34:14 (April 4, 1989), p. 46.

- Kakutani, Michiko A Picaresque Search for Father and for Self. The New York Times, 138 (March 7, 1989), p. C19.

- Klepper, Martin Moon Palace (1989): Marcos Mondfahrt. In: Martin Klepper. Pynchon, Auster, DeLillo: Die amerikanische Postmoderne zwischen Spiel und Rekonstruktion. Frankfurt und New York: Campus Verlag, 1996, pp. 284–298.

- Kornblatt, Joyce Reiser The Remarkable Journey of Marco Stanley Fogg. New York Times Book Review (19.03.1989), pp. 8–9. online text

- Mackey, Mary Desert Mystery Awash in Moonlight. San Francisco Chronicle Review, 1989:11 (March 20, 1989), p. 3.

- Michlin, Monica Bitter Sweet Gravity: Moon Palace. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 217–224.

- Nesbitt, Lois Self-Invention Redux. Princeton Alumni Weekly (March 3–17, 1989), pp. 19–20.

- Parrinder, Patrick Austward Ho. London Review of Books, 11:10 (May 18, 1989), p. 12-13.

- Pesso-Miquel, Catherine ‘Humpty Dumpty had a Great Fall‘: l’Amérique comme lieu de la chute dans Moon Palace de Paul Auster. Études Anglaises, 49:4 (Oct.-Dec. 1996), pp. 476–486.

- Reich, Allon The Promised Land. New Statesman & Society, 2:46 (April 21, 1989), pp. 37–38.

- Reinhart, Werner Die therapeutische Funktion pikaresker Weltsicht: Paul Auster, Moon Palace (1989). In: Werner Reinhart. Pikareske Romane der 80er Jahre: Ronald Reagan und die Renaissance des politischen Erzählens in den U.S.A. (Acker, Auster, Boyle, Irving, Kennedy, Pynchon). Tübingen: Narr, Frühjahr 2001, pp. 177–220.

- Ritchie, Harry Incidents and Accidents. The Sunday Times Books, 8593 (April 23, 1989), p. G6.

- Sacks, David Auster Wild: Further Tales from the Dark Side. Vogue, 179:3 (March 1989), p. 328.

- Sage, Lorna Now Stand Up for Bastards. Observer, 10,304 (April 9, 1989), p. 48.

- Slavitt, Bill A Writer Who’s Too Smart For His Own Good. Applause (April 1989), pp. 39–42.

- Smiley, Jane Searching for Secrets on this Side of the ‚Moon‘. USA Today, 7:128 (March 17, 1898), p. 4D.

- Steinberg, Sybil Fiction: Moon Palace. Publishers Weekly, 234:26 (December 23, 1988), pp. 66–67.

- Vallas, Sophie Moon Palace: Marco autobiographer, ou les errances du Bildungsroman. QWERTY, 6 (Oct. 1996), pp. 225–233.

- Walsh, Robert Preview: Moonstruck. Interview, 19:4 (April 1989), p. 18.

- Walters, Michael In Circulation. The Times Literary Supplement, 4491 (April 28, 1989), p. 452.

- Weisenburger, Steven Inside Moon Palace. In: Dennis Barone (ed.). Beyond the Red Notebook: Essays on Paul Auster. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995, pp. 129–142.

External links

- Around Moon Palace: A conversation with Paul Auster, Marc Chénetier

- Changing Identities in Paul Auster's Moon Palace, Anniken Telnes Iversen