Mons (planetary nomenclature)

Mons /ˈmɒnz/[2] (plural: montes /ˈmɒntiːz/,[2] from the Latin word for "mountain") is a mountain on a celestial body. The term is used in planetary nomenclature: it is a part of the international names of such features. It is capitalized and usually stands after the proper given name, but stands before it in the case of lunar mountains (for example, there is a Martian mountain Arsia Mons and a lunar mountain Mons Argaeus).[3]

The term tholus ("dome") is used for names of smaller (especially domical) uplands, and the term colles ("hills") in names of groups of still smaller knobs. Peculiar round mountains found on Venus get names with the term farrum.[4]

Nature of montes

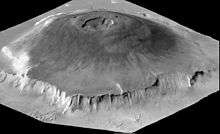

The term mons, like other terms of planetary nomenclature, describes only the external view of the feature, but not its origin or geological structure. It is used for mountains of any origin, and objects in this class are very diverse. Usually they are results of tectonic, impact or volcanic processes. Examples of such mountains are the Maxwell Montes on Venus,[5] the Montes Apenninus on the Moon[6] and Olympus Mons on Mars,[7] respectively. More unusual origins are also possible. For example, the Geryon Montes of Mars are an erosional remnant of a former plateau within Ius Chasma, part of the Valles Marineris canyon system.

During impact events, mountains can appear not only on the border of the resulting crater, but also in its center. Classical central peaks generally are not named, although some peaks within craters are named: for example, Aeolis Mons within Gale crater on Mars or the Scheria Montes within Odysseus crater on Tethys.

Names of montes

The term mons was firstly used for extraterrestrial mountains by Michael van Langren in 1645.[8] He assigned names to some mountains on the Moon,[9] but none of these names remain in use.[10] Two years later Johannes Hevelius proposed[11] the first names of extraterrestrial mountains still used. The lunar Alps and Apennines still bear names given by Hevelius, and five of his other mountain names nowadays refer to other features (in some cases his "mountains" later turned out to be bright rays from craters).[12]

The International Astronomical Union approved the first names of extraterrestrial mountains (together with many other traditional lunar names) in 1935, although without a generic Latin term, which was restored in 1961.[8] As of May 2015, 262 extraterrestrial mountains and mountain systems have official names: 117 on Venus, 50 on Mars, 48 on the Moon, 23 on Io, 13 on Titan, 9 on Iapetus, 1 on Mercury and 1 on Tethys.[3] They are named differently on different celestial bodies:[3][13]

- on Mercury – with word for "hot" in various languages (the only example is Caloris Montes);

- on Venus – after different goddesses of different religions (the only exception is Maxwell Montes);

- on the Moon – after terrestrial mountains and ranges, neighbouring craters or prominent scientists; several names of other origin also exist. In one case (Mont Blanc), the French word "Mont" is used instead of the Latin "Mons";

- on Mars – after a nearby albedo feature on classical maps by Giovanni Schiaparelli or Eugène Antoniadi;

- on Io – after places associated with Io mythology or Dante's Inferno; some names are derived from nearby features;

- on Tethys – after places mentioned in Homer's Odyssey;

- on Titan – after mountains of Tolkien's Middle-earth;

- on Iapetus – after places mentioned in the Chanson de Roland.

See also

- List of tallest mountains in the Solar System

- Lists of extraterrestrial mountains

References

- Fred W. Price (1988). The Moon observer's handbook. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33500-3.

- "Mons". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature". International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- "Descriptor Terms (Feature Types)". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). Archived from the original on 2014-06-23. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- Keep M.; Hansen V. L. (1994). "Structural history of Maxwell Montes, Venus: Implications for Venusian mountain belt formation" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (E12): 26015–26028. Bibcode:1994JGR....9926015K. doi:10.1029/94JE02636. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Bussey, D. B. J.; Spudis, P. D.; Hawke, B. R.; Lucey, P. G.; Taylor, G. J. (1998). "Geology and Composition of the Apennine Mountains, Lunar Imbrium Basin" (PDF). 29th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, March 16–20, 1998, Houston, TX, Abstract No. 1352. (1352): 1352. Bibcode:1998LPI....29.1352B.

- Plescia J. B. (2004). "Morphometric properties of Martian volcanoes". Journal of Geophysical Research. 109 (E3): E03003. Bibcode:2004JGRE..109.3003P. doi:10.1029/2002JE002031.

- Hargitai H. (2014). "Mons, Montes". In H. Hargitai; Á. Kereszturi (eds.). Encyclopedia of Planetary Landforms. Springer New York. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-9213-9_240-1. ISBN 978-1-4614-9213-9.

- Map of the Moon by Michael van Langren (1645)

- Whitaker E. A. (2003). Mapping and Naming the Moon: A History of Lunar Cartography and Nomenclature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–46, 195–200. Bibcode:2003mnm..book.....W. ISBN 9780521544146.

- Hevelius J. (1647). Selenographia sive Lunae descriptio. Gedani: Hünefeld. pp. 226–235. doi:10.3931/e-rara-238. (list of names — on p.228-235)

- Whitaker E. A. (2003). Mapping and Naming the Moon: A History of Lunar Cartography and Nomenclature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–57, 201–209. Bibcode:2003mnm..book.....W. ISBN 9780521544146.

- "Categories for Naming Features on Planets and Satellites". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). Archived from the original on 2014-07-08. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

Links

- Current lists of features with the term Mons or Montes in the name: on Mercury, on Venus, on Moon, on Mars, on Io, on Tethys, on Titan, on Iapetus.