Odysseus (crater)

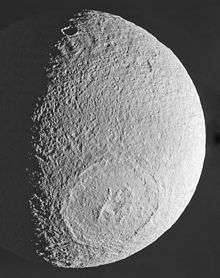

Odysseus is the largest crater on Saturn's moon Tethys. It is 445 km across, more than 2/5 of the moon's diameter, and is one of the largest craters in the Solar System. It is situated in the western part of the leading hemisphere of the moon—the latitude and longitude of its center are 32.8°N and 128.9°W, respectively. It is named after the Greek hero Odysseus from Homer's the Iliad and the Odyssey.[1]

Odysseus was discovered by the Voyager 2 spacecraft on 1 September 1981 during its flyby of Saturn.[2]

Geology

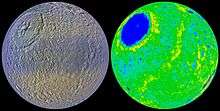

The Odysseus crater is now quite flat for its size of approximately 450 km or more precisely, its floor conforms to Tethys' spherical shape. This is most likely due to the viscous relaxation of the Tethyan icy crust over geologic time. The floor lies approximately 3 km below the mean radius, while its exterior rim is about 5 km above the mean radius—the relief of 6–9 km is not very high for such a large crater. Inside the crater the rim is composed of arcuate scarps and extends for about 100 km until the floor is reached. There are several graben radiating away from Odysseus, which are 10–20 km wide and hundreds of kilometers long. They are likely to be cracks in the crust created by the impact.[3] The most prominent among them is called Ogygia Chasma.[4]

The crater must have originally been deep, with a high mountainous rim and towering central peak. Over time the crater floor has relaxed to the spherical shape of the Tethyan surface, and the crater's rim and central peak have collapsed (similar relaxation is apparent on Jupiter's moons Callisto and Ganymede). This indicates that at the time of the Odysseus impact, Tethys must have been sufficiently warm and malleable to allow the topography to collapse; its interior may have even been liquid. If Tethys had been colder and more brittle at the time of impact, the moon might have been shattered, and even if it survived the impact, the topography of the crater would have retained its shape, similarly to the crater Herschel on Mimas.[5][6]:642

The central complex of Odysseus (Scheria Montes)[7] features a central pit-like depression,[6]:642 which is 2–4 km deep. It is surrounded by massifs elevated by 2–3 km above the crater floor, which itself is about 3 km below the average radius.[3]

Relation to Ithaca Chasma

The immense trench called Ithaca Chasma, which approximately follows a great circle with a pole near Odysseus' center, had been hypothesized to have formed as a result of the Odysseus impact.[3] However, a study based on high resolution Cassini images indicated that this is unlikely—the crater counts inside Odysseus appear to be lower than in Ithaca Chasma, indicating that the latter is older than the former.[8][6]:669

References

- "Tethys: Odysseus". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- Stone, E. C.; Miner, E. D. (29 January 1982). "Voyager 2 Encounter with the Saturnian System" (PDF). Science. 215 (4532): 499–504. Bibcode:1982Sci...215..499S. doi:10.1126/science.215.4532.499. PMID 17771272.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Jeffrey M.; Schenk, Paul M.; Bruesch, Lindsey S.; Asphaug, Erik; McKinnon, William B. (October 2004). "Large impact features on middle-sized icy satellites" (PDF). Icarus. 171 (2): 421–443. Bibcode:2004Icar..171..421M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009.

- "Tethys: Ogygia Chasma". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- Hamilton, Calvin J. (19 February 1999). "Odysseus Basin on Saturn's Moon Tethys". SolarViews.com. SolarViews. Retrieved 19 December 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jaumann, R.; Clark, R. N.; Nimmo, F.; Hendrix, A. R.; Buratti, B. J.; Denk, T.; Moore, J. M.; Schenk, P. M.; Ostro, S. J.; Srama, Ralf (2009). "Icy Satellites: Geological Evolution and Surface Processes". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 637–681. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_20. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- "Tethys: Scheria Montes". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- Giese, B.; Wagner, R.; Neukum, G.; Helfenstein, P.; Thomas, P. C. (2007). "Tethys: Lithospheric thickness and heat flux from flexurally supported topography at Ithaca Chasma" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (21): 21203. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3421203G. doi:10.1029/2007GL031467.