Molenbeek-Saint-Jean

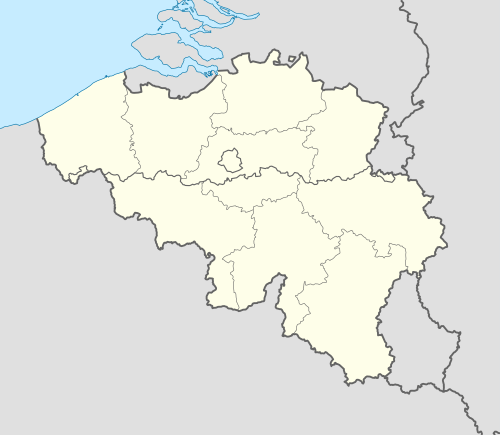

Molenbeek-Saint-Jean (French, pronounced [molənbeːk sɛ̃ ʒɑ̃]) or Sint-Jans-Molenbeek (Dutch, pronounced [sɪn ˈcɑns ˈmoːlə(m)ˌbeːk] (![]()

Municipal Square of Molenbeek | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Coordinates: 50°51′28″N 04°18′57″E | |

| Country | Belgium |

| Community | Flemish Community French Community |

| Region | Brussels |

| Arrondissement | Brussels |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Catherine Moureaux (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.89 km2 (2.27 sq mi) |

| Population (2018-01-01)[1] | |

| • Total | 97,005 |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (43,000/sq mi) |

| Postal codes | 1080 |

| Area codes | 02 |

| Website | www |

As of 1 January 2014, Molenbeek had a population of 94,854 inhabitants.[2] It is densely populated, at 16,357/km2 (42,360/sq mi), twice the average of Brussels. Its upper area is greener and less densely populated.

In 2015, Molenbeek gained international attention as the base of Islamist terrorists, who carried out attacks in both France and Belgium. The municipality's then-mayor described it as "a breeding ground for violence".[3] In early 2016, Molenbeek held a reputation as a safe haven for jihadists in relation to the support shown by some residents towards the bombers who carried out the Paris and Brussels attacks.[4][5][6][7]

Etymology

The name Molenbeek derives from two Dutch words: molen, meaning "mill", and beek, meaning "brook". Although first applied to the brook that ran through the village, the name eventually came to be used to designate the village itself, around the year 985. The suffix Saint-Jean in French or Sint-Jans in Dutch refers to the parish's patron saint: Saint John the Baptist.

History

Rural beginnings

As early as the 9th century, Molenbeek was the site of a church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist. In the early Middle Ages, Molenbeek was known for its miraculous well of Saint Gertrude of Nivelles, which attracted thousands of pilgrims.

_by_Pieter_Brueghel_II.jpg)

The village was made part of Brussels in the 13th century. As a result, Molenbeek lost a lot of its land to its more powerful neighbour. In addition, its main church was dismantled in 1578, leading to further decline. The town's character remained mostly rural until the 18th century.

Industrialisation

At the end of the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution and the building of the Brussels–Charleroi Canal brought prosperity back to Molenbeek through commerce and manufacturing. In 1785, the town regained its status as an independent municipality. Attracted by the industrial opportunities, many workers moved in, first from other Belgian provinces and France, then from South European, and more recently from East European and African countries.

_12-02-2010_15-07-38.jpg)

The growth of the community continued unabated throughout the 19th century, leading to cramped living conditions, especially near the canal. The town became known as Little Manchester or the Belgian Manchester.[8][9] On 5 May 1835, Molenbeek was the departure site of the first passenger train in continental Europe.[10][11] At the end of the 19th century, Brussels reintegrated the canal area within its new port, which was thus lost to Molenbeek.

20th century

Until the early 20th century, Molenbeek was a booming suburb which attracted a large working-class population. The industrial decline, which had already started before World War I, accelerated after the Great Depression.

Following the industrial decline after the war, the districts bordering the City of Brussels began to decrease in population. This was not addressed until the 1960s through the construction of new residential areas in the then-rural west of the town. In 1990, this expansion was halted, leaving some woods and meadows in Molenbeek: the Scheutbos.[12]

Where Molenbeek was once a centre of intense industrial activity, concentrated around the canal and the railway, most of those industries have disappeared to make way for large-scale urban renewal following the modernist Athens Charter. The industrial past is remembered in a museum of social and industrial history built on the site of the former foundry of the Compagnie des Bronzes de Bruxelles.[9]

21st century

In some areas of the town, the ensuing poverty left its mark on the urban landscape and scarred the social life of the community, leading to rising crime rates and pervading cultural intolerance. Various local revitalisation programmes are currently under way, aiming at relieving the most impoverished districts of the municipality.

Attempts at revitalising the municipality have, however, not been successful. In June 2011, the multinational company BBDO, citing over 150 attacks on their staff by locals, posted an open letter to then-mayor Philippe Moureaux, announcing its withdrawal from the town.[13] As a result, serious questions were raised about governance, security and the administration of Moureaux.[14]

Terrorism

According to Le Monde, the assassins who killed anti-Taliban commander Ahmed Shah Massoud both came from Molenbeek.[15] Hassan el-Haski, one of the 2004 Madrid terror bombers, came from Molenbeek.[16][17] The perpetrator of the Jewish Museum of Belgium shooting, Mehdi Nemmouche, lived in Molenbeek for a time.[18] Ayoub El Khazzani, the perpetrator of the 2015 Thalys train attack, stayed with his sister in Molenbeek.[19] French police believe the weapons used in the Porte de Vincennes siege two days after the Charlie Hebdo shooting were sourced from Molenbeek.[20] The bombers of the November 2015 Paris attacks were also traced to Molenbeek;[21] during the Molenbeek capture of Salah Abdeslam, an accomplice of the Paris bombers, protesters "threw stones and bottles at police and press during the arrest", stated the then-Interior Minister of Belgium, Jan Jambon.[22] Oussama Zariouh, the bomber of Brussels Central Station in June 2017,[23] lived in Molenbeek.[24]

November 2015 Paris attacks

At least four of the terrorists in the November 2015 Paris attacks — the brothers Brahim and Salah Abdeslam, alleged accomplice Mohamed Abrini, and the alleged mastermind Abdelhamid Abaaoud — grew up and lived in Molenbeek. According to former French President François Hollande, that was also where they organised the attacks.[25] On 18 March 2016, Salah Abdeslam, a suspected accomplice in those attacks, was captured in two anti-terrorist raids in Molenbeek that killed another suspect and injured two others. At least one other suspect remains at large.[26][27][28][29] Ibrahim (born 9 October 1986 in Brussels) was involved in the attempted robbery of a currency exchange office in January 2010, where he shot at police with a Kalashnikov rifle. The then-mayor of Brussels, Freddy Thielemans, and the then-mayor of Molenbeek, Philippe Moureaux, described the shooting as a "fait divers" (a small daily news item) and "normal in a large city", causing controversy.[30]

Police investigation

Since several of the attackers in the Brussels and Paris terrorist attacks had connections to the area, Belgian police started door-to-door checks in which a quarter of Molenbeek's inhabitants were investigated, a total of 22,668. This operation resulted in that of the 1,600 organisations investigated, 102 were found to be involved with crime and a further 52 were involved with terrorism. 72 individuals were found to have a terrorist connection and were subject to future surveillance.[31][32]

Districts

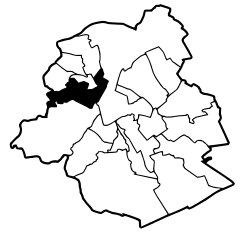

.jpg)

There are two distinct areas in Molenbeek: a lower area and a higher area. The lower area, next to the canal, consists of working-class, mainly migrant, communities, mostly of Moroccan and Turkish descent, with many being second- and third-generation. The higher area, close to Brussels' second ring road, features newer construction and is mostly middle-class and residential.[33]

Molenbeek has seven large districts:

- Centre (Parvis)

- Duchesse (Quatre-vents)

- Heyvaert

- Karreveld

- Machtens (Marie-José)

- Maritime

- Scheutbos-Cimetière (Mettewie)

The area along the canal is currently experiencing a large revitalisation programme, as part of the Plan Canal of the Brussels-Capital Region.[34]

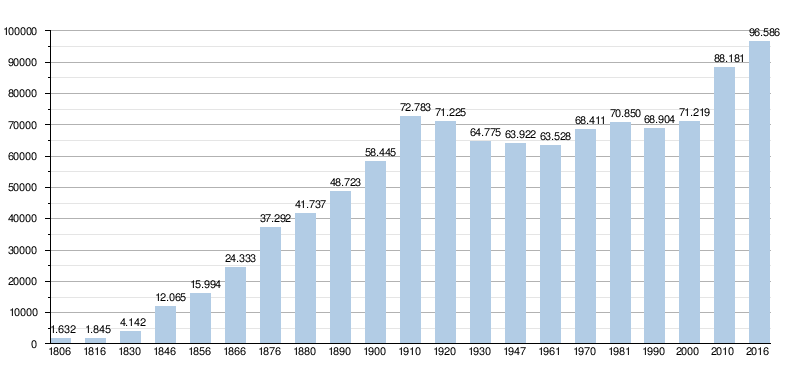

Demographics

The population, as of 1 January 2015, was 95,576.[35] The area is 5.9 km2 (2.3 sq mi), making the density 16,357/km2 (42,360/sq mi). The population has been described as "mainly Muslim" in the media;[8] however, actual figures range between 25% and 40%, depending on the catchment area. The population of Molenbeek itself, while already impoverished and overcrowded, has further increased by 24.5% in the last decade.[36]

As of 2016, there is one main minority group in Molenbeek, Belgian Moroccans. That year, Françoise Schepmans, then-mayor of Molenbeek, stated that the lack of diversity in the foreign population of Molenbeek and the fact they are all clustered in the same area is a problem.[37] Nearly 40% of young people in Molenbeek are unemployed. The municipality lies in a semi-circle of neighbourhoods in Brussels often referred to as the "poor croissant".[37]

Historical population

- Sources: INS: 1806 to 1981= census; 1990 and later = population on January 1

Politics

Molenbeek is governed by an elected municipal council and an executive college of the mayor and aldermen. The longtime mayor from 1992 to 2012 was Philippe Moureaux (PS). Following the Belgian local elections, 2012, an alternative majority was formed headed by then-mayor Françoise Schepmans (MR) and consisting of MR (15 seats), CDH-CD&V (6 seats) and Ecolo-Groen (4 seats). The Socialist Party (16 seats) became the opposition next to the Workers' Party of Belgium (PTB), Democratic Federalist Independent (DéFI), the ISLAM party and the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), each having one seat.

Mayor

Historical list of mayors or burgomasters of Molenbeek:

- 1800–1812: J.-B. De Roy

- 1812–1818: FR. De Putte

- 1818–1819: V. Van Espen

- 1819–1830: F. Vanderdussen

- 1830–1836: Ch. Deroy

- 1836–1842: P.-J. Meeüs

- 1843–1848: A. Vander Kindere

- 1848–1860: H.-J.-L. Stevens

- 1861–1863: J.-B. De Bauche

- 1864–1875: L.-A. De Cock

- 1876–1878: G. Mommaerts

- 1879–1911: Henri Hollevoet (liberal)

- 1914–1938: Louis Mettewie (liberal)

- 1939–1978: Edmond Machtens (PSB)

- 1978–1988: Marcel Piccart (PS, later FDF)

- 1988–1992: Léon Spiegels (PRL)

- 1992–2012: Philippe Moureaux (PS)

- 2013–2018: Françoise Schepmans (MR)

- 2018–present: Catherine Moureaux (PS)

Sports

Football

The Molenbeek football team Racing White Daring Molenbeek, often referred to as RWDM, was a very popular football club until its dissolution in 2002. Its successor, R.W.D.M. Brussels F.C., used to play in the Belgian first division. It folded at the end of 2012–13 as a member of the Belgian Second Division. Since 2015, its reincarnation RWDM47 is back playing in the fourth division.

Education

There are 17 French-language and six Dutch-language primary schools in Molenbeek.[38]

Secondary schools:

Points of interest

Several rundown industrial buildings have been renovated and converted into prime real estate and other community functions. Examples include:

- The Fonderie, a former smelter of the Compagnie des Bronzes de Bruxelles, operational from 1854 to 1979, now home to Brussels' Museum of Industry and Labour. The museum focuses on the industry, coupled with the social history of the Molenbeek, and the impact of industrialisation on the development of the municipality.[9]

- The Raffinerie, a former sugar refinery, now the site of a cultural and modern dance complex.

- The Bottelarij, a bottling plant that housed the Royal Flemish Theatre during its renovation in the centre of Brussels.

- The Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art (MIMA), a museum dedicated to culture 2.0 and to urban art opened in April 2016, in the former buildings of the brewery Belle-Vue, and is the first of the kind in Europe.[42]

- The impressive buildings of the former goods station of Tour & Taxis and the surrounding area bordering the municipality, which will be turned into residences, as well as commercial enterprises.

- Brussels' Circus School, installed in the buildings of Tour & Taxis.[43]

- A brewery, the Brasserie de la Senne.

Other points of interest include:

- The Town Hall of Molenbeek, in eclectic style, located on the Municipal Square.[44]

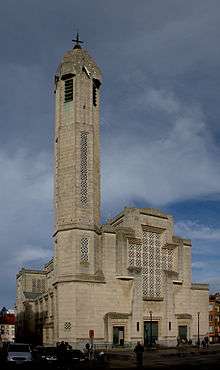

- The Church of St. John the Baptist, an Art Deco Roman Catholic church built between 1931–1932,[45] which has been listed as a protected monument since 1984.[46]

- The neo-Gothic Church of Saint Remigius, completed in 1907.[47]

- The Church of Saint-Barbara, another neo-Gothic building, completed in 1894 and listed since 1998.[48]

- The Molenbeek Cemetery contains remarkable monuments, including funerary galleries and a columbarium built in 1880.[49]

- The Municipal Museum of Molenbeek (MoMuse), housed in the prestigious building of the Academy of Drawing and Visual Arts.[50]

- The Vaartkapoen statue, on Sainctelette Square.

- The Karreveld Castle and surrounding park is used for cultural events and the meetings of the municipal council. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was one of the birth places of Belgian Cinema. At the request of Charles Pathé (Pathé Cinéma), the director Alfred Machin commissioned the first film studio in the country, together with a workshop for the construction of film sets and a mini zoological garden for exotic animals, such as bears, camels and panthers used as 'extras' in films. Several films, including the first two Belgian feature films La Fille de Delft and the sadly prophetic Maudite soit la guerre (in hand-painted colours) were shot by Alfred Machin in the studio of the Karreveld Castle. Since 1999, the castle hosts from mid-July to September the Festival Bruxellons!,[51] a theatre festival open to other performing arts (magic, music, circus, etc.)

Karreveld Castle

Karreveld Castle

Transportation

Road network

The main roads that cross Molenbeek are Boulevard Léopold II/Leopold II-laan, Chaussée de Gand/Steenweg op Gent and Chaussée de Ninove/Ninoofsesteenweg running east-west, as well as Boulevard Mettewie/Mettewielaan running north-south.

Public transport

Molenbeek is served by Brussels' metro lines 1, 2, 5 and 6. Brussels-West and Beekkant metro stations are connected to all of Brussels' metro lines and are multi-modal transport hubs in western Brussels. The former will also gain importance in the framework of the Brussels RER/GEN development. Additionally, a comprehensive bus a tram service links Molenbeek to other parts of the region. The municipality also has a number Villo! public bicycle stations on its territory.

Parks and green spaces

Green spaces in the municipality include:[52]

- Scheutbos Park, a regional nature park of 6 ha (15 acres)

- Semi-natural site of the Scheutbos, a protected area of 44 ha (110 acres)

- Karreveld Park 3 ha (7.4 acres)

- Marie-José Park 6 ha (15 acres)

- Albert Park

- Muses' Park

- Hauwaert Park

- Bonnevie Park

- Fonderie Park

Notable inhabitants

- Salah Abdeslam (b. 1989), jihadist terrorist

- Richard Beauthier (1913–1999), Belgian politician, was born there.

- Norbert Benoit (Norbert Benoit Van Peperstaete) (1910–1993), filmmaker

- Louis Bertrand (1856–1943), politician

- Ado Chale (b. 1928), Belgian artist

- Serge Creuz (1924–1996), painter

- Jean De Middeleer (1908–1986), Belgian musician

- Eugène Demolder (1862–1919), writer

- Joseph Diongre (1878–1963), modernist architect

- Alfred Dubois (1898–1949), professor at the Brussels Conservatory, violinist and teacher of the Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux

- Alexis Dumont (1877–1962), architect of the Citroën building, was born there.

- Ferdinand Elbers (1862–1943), mechanic, trade unionist, and politician

- Hendrik Fayat (1906–1997), politician

- Eugene Hins (1839–1923), founder of the newspaper La Pensée, leader of the Belgian freethinking movement and co-founder of the Socialist International.

- Marcel Josz (1899–1984), actor, was born there

- Eugène Laermans (1864–1940), painter

- Daniel Leyniers, Esquire (1881–1957), equerry, politician and senator, was born there.

- Marka, Serge Van Laeken (b. 1961), singer, songwriter, composer and film-maker

- Pierre-Joseph Meeûs-Vandermaelen (1793–1873), mayor of Neder-over-Heembeek in 1830 and Molenbeek-Saint-Jean from 1836 to 1842, registrar of the Court of Auditors from 1831 to 1836, decorated with the Iron Cross (Belgium), etc. He lived at 7, Faubourg de Flandre.

- Henry Meuwis (1870-1935), Painter.

- Philippe Moureaux (1939–2018), politician, senator, mayor, and professor of economic history at the Université Libre de Bruxelles

- Michel Mourlon (1845–1915), geologist, paleontologist, and curator of the Museum of Natural Sciences of Belgium.

- Jean Muno (1924–1988), writer

- Geo Norge (1898–1990), poet

- Zeynep Sever (b. 1989), Miss Belgium 2008

- Jean Stampe (1889–1978), war pilot, aircraft manufacturer including the famous Stampe SV-4

- Eric Struelens (b. 1969), professional basketball player

- Herman Teirlinck (1879–1967), writer

- Pierre Tetar van Elven (1828–1908), painter

- Toots Thielemans(1922–2016),[53] jazz artist

- Henri Thomas (1878–1972), painter

- Pierre Van Humbeeck (1829–1890), minister

- Leon Vanderkindere (1842–1906), historian and prominent professor at the Free University of Brussels, was born there.

- Philippe Vandermaelen (1795–1869), world-renowned geographer and cartographer. He founded the geographical establishment of Brussels in Molenbeek.

- Franky Vercauteren (b. 1956), Belgian football personality.

- Firmin Verhevick (1874–1962), painter, was born there.

- Oussama Zariouh (1981–2017), Moroccan terrorist responsible for the Brussels Central Station bombing in 2017.

- Thierry Zéno (1950–2017), author-filmmaker

Twin cities

References

- "Wettelijke Bevolking per gemeente op 1 januari 2018". Statbel. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- "Chiffres-clés par commune — fr". ibsa.irisnet.be. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Levitt, Matthew (27 March 2016). "My Journey To Brussels' Terrorist Safe Haven". Politico.

- "Brussels attacks: Molenbeek's gangster jihadists". BBC. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "The Belgian neighborhood indelibly linked to jihad". Washington Post. 15 November 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Beleaguered Molenbeek struggles to fend off jihadist recruiters". The Times of Israel. 3 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "World points to "jihad Capital" Molenbeek". Het Niuewsblad. 16 November 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Paris attacks: Visiting Molenbeek, the police no-go zone that was home to two of the gunmen". The Independent. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Fun, Everything is (10 March 2017). "La Fonderie - Brussels Museum of Industry and Work". Brussels Museums. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Wolmar 2010, p. 20.

- "Histoire en quelques mots — Français". molenbeek.irisnet.be. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "Scheutbos: grand espace vert bruxellois". www.scheutbos.be. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Insécurité à Molenbeek" [Insecurity in Molenbeek]. La Capitale (in French). 17 June 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- "BBDO zwaar ontgoocheld in Moureaux" [BBDO greatly disappointed by Moureaux]. De Standaard (in Dutch). 17 June 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Stroobants, Jean Pierre (16 November 2015). "Molenbeek, la plaque tournante belge du terrorisme islamiste". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 12 April 2016.

c’est de Molenbeek que sont partis les tueurs du commandant afghan Ahmed Shah Massoud, principal adversaire du régime des talibans, assassiné par deux faux journalistes.

- Bartunek, Robert-Jan; Lewis, Barbara (15 November 2015). "Belgian connection: three held in Brussels over Paris attacks". Reuters. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

A prominent, Moroccan-born member of the group behind the 2004 Madrid train bombings that killed 191 was from Molenbeek.

- "Why did the bombers target Belgium?". The Guardian. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Hassan el-Haski – Madrid and Casablanca bombings - A Spanish judge sentenced Haski to 14 years in jail for belonging to a terrorist organisation, in connection with the March 2004 attacks on Madrid.

- Newton-Small, Jay (16 November 2015). "The Belgian Suburb at the Heart of the Paris Attacks Probe". Time. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

May 2014, three people were killed and one injured in a shooting at the Jewish Museum of Belgium by alleged terrorist Mehdi Nemmouche, who is awaiting trial and spent time in Molenbeek

- Torfs, Michaël (25 August 2015). " 'Suspect lived in Brussels before attempted Thalys attack' ". De Redactie.

- Lewis, Barbara; Bartunek, Robert-Jan (15 November 2015). "Belgian connection: three held in Brussels over Paris attacks". Reuters. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Molenbeek. The area has been connected with two attacks in France this year. Security officials have said the Islamist who killed people at a Paris kosher grocery in January at the time of the attack on the magazine Charlie Hebdo acquired weapons in the district.

- Lynch, Julia (5 April 2016). "Here's why so many of Europe's terrorist attacks come through this one Brussels neighborhood". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Molenbeek had been linked to radical Islamist terrorism. One of 19 'communes' in the Brussels metro area, the neighborhood was home to one of the attackers in the 2004 commuter train bombings in Madrid and to the Frenchman who shot four people at the Jewish Museum in Brussels in August 2014. The Moroccan shooter on the Brussels-Paris Thalys train in August 2015 stayed with his sister there. French police suspect that the weapons used in the Paris supermarket attack connected with the Charlie Hebdo attack in January 2015 were acquired in Molenbeek, and the attackers in the November 2015 Paris bombings were traced to Brussels by way of a parking ticket issued on a rental car in Molenbeek.

- "Belgian minister says many Muslims 'danced' after attacks". Agence France-Presse. 16 April 2016. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

They threw stones and bottles at police and press during the arrest of Salah Abdeslam. That is the real problem.

- "Brussels station suspect had 'nail bomb'". BBC News. 21 June 2017.

- "L'auteur de l'attentat manqué de Bruxelles avait des "sympathies" pour l'État islamique". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 21 June 2017.

L'homme abattu par les soldats à la gare centrale de Bruxelles était un Marocain de 36 ans. Il vivait à Molenbeek

- "Paris attacks: Belgian Abdelhamid Abaaoud identified as presumed mastermind". CBC News. 16 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- "Shots in Brussels raid tied to Paris attacks". CNN. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Gunfire in Brussels raid on 'Paris attacks suspects'". BBC News. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Paris attacks suspect Salah Abdeslam shot, arrested in Brussels raid". Russia Today. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Paris attacks: Salah Abdeslam 'worth his weight in gold'". BBC News. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Schietpartij in Anderlecht was fait divers". Het Laatste Nieuws. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "Belgium's Molenbeek home to 51 groups with terror links: report". Politico. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "51 Molenbeekse vzw's verdacht van terreurbanden". De Morgen. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Molenbeek-Saint-Jean". be.brussels. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- "Plan canal: des ambitions, une méthode, une équipe | Canal.brussels". canal.brussels. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- "Molenbeek-Saint-Jean (Commune, Region of Brussels)". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- "La population de Molenbeek augmente de 25% en 10 ans" [The population of Molenbeek increases 25% in 10 years]. l'avenir.net (in French). Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Capadites, Christina (11 April 2016). "Molenbeek and Schaerbeek: A tale of two tragedies". CBS News. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Ecoles communales fondamentales"/"Gemeentelijke basisscholen." Sint-Jans-Molenbeek. Retrieved on September 8, 2016.

- "Autres écoles — Français". Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "Campus Toverfluit".

- "Andere scholen — Nederlands". Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "MIMA : ouverture d'un musée du street art au coeur de Molenbeek". Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- "École de Cirque de Bruxelles – École de Cirque de Bruxelles" (in French). Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "The Maison Communale at Molenbeek". visit.brussels. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Church of St John the Baptist in Molenbeek". visit.brussels. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Molenbeek-Saint-Jean - église Saint-Jean-Baptiste - Parvis Saint-Jean-Baptiste - DIONGRE Joseph". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Molenbeek-Saint-Jean - Eglise Saint-Rémi - VERAART Chrétien". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "Molenbeek-Saint-Jean - Eglise Sainte-Barbe - Place de la Duchesse de Brabant - PEPERMANS Léopold". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Molenbeek-Saint-Jean - Cimetière communal de Molenbeek-Saint-Jean - Chaussée de Gand 537, 539 - PRAET". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "MoMuse - MuséeMolenbeekMuseum". www.momuse.be. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Festival Bruxellons!".

- "Espaces verts à Molenbeek-Saint-Jean — Français". molenbeek.irisnet.be. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- "Toots, an icon of the Brussels jazz scene". Visitbrussels.be. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

Bibliography

- Wolmar, Christian (2010). Blood, Iron & Gold: How the Railways transformed the World. London: Grove Atlantic. ISBN 9781848871717.

Further reading

- Lamfalussy, Christophe; Martin, Jean-Pierre (2017). Molenbeek-sur-djihad. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 9782246862765.

- Chalmers, Robert (April 2017). "Is Molenbeek really a no-go zone?". British GQ.

- "Molenbeek: Life Inside the So-Called 'Jihadi Capital of Europe". ABC News. 3 April 2016.

External links

![]()

- Official website