Al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra

Abū Saʿīd al-Muhallab ibn Abī Ṣufra al-Azdī (Arabic: أَبْو سَعِيْد ٱلْمُهَلَّب ابْن أَبِي صُفْرَة ٱلْأَزْدِي; c. 632 – 702) was an Arab general from the Azd tribe who fought in the service of the Rashidun, Umayyad and Zubayrid caliphs between the mid-640s and his death. He served successive terms as the governor of Fars (685–686), Mosul, Arminiya and Adharbayjan (687–688) and Khurasan (698–702). Al-Muhallab's descendants, known as the Muhallabids, became a highly influential family, many of whose members held high office under various Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs, or became well-known scholars.

Al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra al-Azdi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Zubayrid governor of Fars | |

| In office 685–686 | |

| Monarch | Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr (r. 683–692) |

| Zubayrid governor of Mosul[note 1] | |

| In office 687–688 | |

| Monarch | Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr (r. 683–692) |

| Preceded by | Ibrahim ibn al-Ashtar |

| Succeeded by | Ibrahim ibn al-Ashtar |

| Umayyad governor of Khurasan[note 2] | |

| In office 698–702 | |

| Monarch | Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705) |

| Preceded by | Umayya ibn Abdallah ibn Khalid ibn Asid |

| Succeeded by | Yazid ibn al-Muhallab |

| Personal details | |

| Born | ca. 632 |

| Died | 702 Marw al-Rudh, Umayyad Caliphate |

| Spouse(s) | Khayra al-Qushayriyya Bahla |

| Children | Abd al-Malik Habib Marwan Mudrik Al-Mufaddal Muhammad Al-Mughira Qabisa Yazid Ziyad |

| Parents | Abu Sufra |

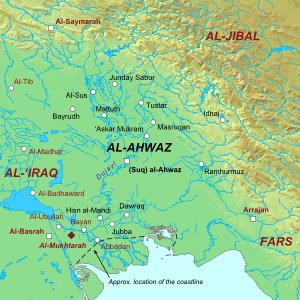

Throughout his early military career, he participated in the Arab campaigns against the Persians in Fars, Ahwaz, Sistan and Khurasan during the successive reigns of caliphs Umar (r. 634–644), Uthman (r. 644–656), Ali (r. 656–661) and Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680). By 680, his tribe, the Azd of Oman, had become a major army faction in the Arabs' Basra garrison, the launchpad for the Persian conquest. Following the collapse of Umayyad rule in Iraq and Khurasan in 683–684, during the Second Muslim Civil War, al-Muhallab was pressed by the Basran troops to lead the campaign against the Azariqa, a Kharijite faction which had taken over Ahwaz and threatened Basra. Al-Muhallab landed them a severe blow and drove them into Fars in 685. He was rewarded with the governorship of that province by the anti-Umayyad caliph Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr (r. 683–692), whose suzerainty had been recognized in Basra in the wake of the Umayyads' ouster. Al-Muhallab later held a command role in the successful Zubayrid campaign to eliminate the Kufa-based ruler al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi in 686/87. After this victory, he was transferred to the governorship of Mosul, where he was charged with protecting Iraq from a potential invasion from Umayyad-controlled Syria.

The resurgence of the Azariqa in Ahwaz in 688/89 saw him transferred once again to that front by the Zubayrids. When the latter were ousted from Iraq by the Umayyads in 691, al-Muhallab switched allegiance to the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705), who kept him in command of the war with the Azariqa. With the key support of the powerful Umayyad governor of Iraq, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, al-Muhallab decisively defeated the Kharijites in 698. Throughout the thirteen-year conflict with the Kharijites, al-Muhallab was consistently viewed as indispensable by the Basrans and their successive Zubayrid and Umayyad rulers. Al-Hajjaj made al-Muhallab governor of Khurasan in 698. From there, he recommenced the Arab conquests in Transoxiana, leading a two-year-long siege of the fortress of Kish. He was ultimately compelled to withdraw to his capital in Merv and died on the way there. He was succeeded by his son Yazid ibn al-Muhallab.

Origins, early life and career

Al-Muhallab was born in c. 632.[1] Most Muslim sources hold that his father, Abu Sufra, was an Arab from the Azd tribe, with 9th-century historian al-Baladhuri asserting that he belonged to one of the tribe's noble households,[1] the Atik of the Dibba coast.[3] However, according to another 9th-century scholar, Abu Ubayda, Abu Sufra was a Persian weaver who migrated from Kharak (Karachi) to Oman before settling in the Arab garrison town of Basra in Iraq. According to this account, he was accepted by the Azd as one of their own by dint of the courage he demonstrated in battle.[1] The Azd had dominated Oman (Uman) since the pre-Islamic era and hence were known as the "Azd Uman" to distinguish them from the "Azd Sarat", who were based in western Arabia.[4]

Al-Muhallab and his father were initially settled among the Azd Uman at the Arab military settlement of Tawwaj in Fars.[1] This likely marked the start of al-Muhallab's military career.[1] During the reign of Caliph Umar (r. 634–644) al-Muhallab participated in operations against the Persians in Ahwaz.[1] He later fought them in Sistan in 653/54, during the reign of Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656).[1] In 656, during the reign of Caliph Ali (r. 656–661), al-Muhallab and his father were moved to Basra.[1] Though in the reports cited by 9th-century historians al-Tabari and al-Awtabi, Ali declared Abu Sufra the chief of Azd, the modern historian Patricia Crone holds that "neither Abu Sufra nor al-Muhallab ever held" the chieftainship of the Basran Azd.[1] Rather, they gained prestige and power through their military prowess not their tribal status.[1] At some point during Ali's caliphate, al-Muhallab fought again in Ahwaz.[1]

Between 662 and 665, during the reign of the Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), al-Muhallab led a renewed campaign into Sistan, reaching as far as Sindh.[1] In 664, he attacked Banna and al-Ahwar (Lahore), but was countered by local forces.[5] There, he adopted the Indian tradition of trimming the tails of his war horses.[1] After his Sistan campaign, he was transferred, for an unspecified period, to the Khurasan front in 670, fighting under the command of al-Hakam ibn Amr al-Ghifari.[1] He returned to this front under the governor of Khurasan, Sa'id ibn Uthman, in 676 and then again in 681, in the company of other reputable Basran generals recruited by the newly-appointed governor, Salm ibn Ziyad.[1] This time he remained in the province for a further three years, after which Umayyad authority collapsed in Khurasan and most of the Caliphate.[1] Salm consequently left the province, initially appointing al-Muhallab as his deputy governor, but the latter was quickly edged out by Abd Allah ibn Khazim al-Sulami.[1] The latter had the backing of the Banu Tamim, a powerful tribal faction in the Khurasan army, while al-Muhallab lacked tribal support as the Azd presence in the province was negligible at the time.[6]

Iraq, and Khurasan with it, ultimately came under the suzerainty of the anti-Umayyad, Mecca-based caliph, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr (r. 683–692), who appointed al-Muhallab governor of Khurasan.[1] Meanwhile, a mass wave of Azdi tribesmen from Oman had migrated to Basra between 679 and 680, merged with the Azd Sarat already present in the city and formed a strong alliance with the Rabi'a tribal confederation, a major faction in the Basran garrison.[4] After Yazid's governor in the city, Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, was ousted in the aftermath of the caliph's death, the Azdi leader of the Azd–Rabi'a alliance, attempted to gain control of the city and was killed by members of the rival Banu Tamim, the other major faction of the Basran garrison.[4] This precipitated hostilities between the two groups, which spread to Khurasan where troops from both factions were deployed.[4]

First campaign against the Kharijites

Al-Muhallab was unable to take up his assignment in Khurasan due to the opposition of the Basran troops, who pressed him to lead the campaign against the Azariqa, a Kharijite faction that threatened the city.[1] The conflict between the Azd–Rabi'a alliance and the Tamim had strengthened the Azariqa in Ahwaz and spurred them to assault Basra.[7] The Basran troops sent to engage them were defeated and panic ensued in the city.[7] For many months, the Azariqa pillaged the areas between Basra and Ahwaz, killing those who refused to accept their doctrine.[8] When al-Muhallab reached Basra after arriving from Mecca on his way to Khurasan, the leader of the Tamim, al-Ahnaf ibn Qays, proclaimed to the Basran garrison and its Zubayrid governor, al-Harith ibn Abi Rabi'a al-Makhzumi, that "only al-Muhallab" was capable of defeating the Azariqa.[9] After al-Muhallab refused their initial entreaties, the Basran nobles forged a letter from Ibn al-Zubayr calling on him to abandon his assignment to Khurasan and confront the Kharijites instead, which he accepted after securing assurances of loyalty from the troops and sufficient funds from the provincial treasury.[10]

The campaign against the Kharijites "was to occupy him [al-Muhallab], on and off, for the next thirteen years", according to Crone.[1] Under his command, the Zubayrid forces ousted the Azariqa from the Tigris river valley, forcing them to regroup at a place in Ahwaz called Sillabra, where he inflicted a decisive defeat against them in 685,[8][11] in which 7,000 of their men were killed.[12] The Azariqa consequently retreated east into Fars.[8] Al-Muhallab remained in Ahwaz for a short period until Ibn al-Zubayr's brother, Mus'ab, became governor of Basra.[13] The latter appointed al-Muhallab governor of Fars.[14]

Zubayrid governor of Mosul

By 686/87, al-Muhallab had dispersed the Azariqa in the regions of Basra and Ahwaz and was called on by Mus'ab to join his campaign against al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, the ruler of Kufa.[1] With the key backing of the local mawali, al-Mukhtar had recently suppressed a rebellion by Kufa's Arab nobility, prompting thousands of them to seek refuge and support from Mus'ab in Basra.[14] One of the leading Kufan nobles, Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath, pressed Mus'ab to march against al-Mukhtar, but the former refused unless al-Muhallab agreed to join.[14] After Ibn al-Ash'ath persuaded al-Muhallab to that effect, the latter arrived in Basra "bringing many troops and much money with him, with such troops and in such a state of readiness as none of the people of al-Basrah could match", according to historian Abu Mikhnaf.[14] He was made commander of the Basran army's left wing at the Battle of Madhar, then commander of the right wing at the Battle of Harura, both of which ended in Zubayrid victories over al-Mukhtar's forces.[15] After Kufa was captured and al-Mukhtar killed in early 687, Mus'ab appointed al-Muhallab governor of Mosul, the Jazira, Armenia and Adharbayjan.[1][16] He replaced al-Mukhtar's governor over these areas, Ibrahim ibn al-Ashtar, who joined the Zubayrids after their victory in Kufa and was transferred to that city.[17] As governor over the region wedged between Zubayrid-controlled Iraq and Umayyad-controlled Syria, al-Muhallab was tasked with protecting the former from an Umayyad invasion.[1][18] He was also charged with ridding his province of al-Mukhtar's surviving loyalists, the Khashabiyya, who remained in control of Nisibis.[1]

Final campaign against the Kharijites

Al-Muhallab was recalled from Mosul to confront the Azariqa's resurgence and renewed raids against Ahwaz, and Ibn al-Ashtar replaced him as governor.[1][8][19] Despite the intensified efforts of al-Muhallab, the Azariqa's defense kept him confined to the west bank of the Dujayl river.[8] In 690, eight months after he was reassigned to the war against the Azariqa, Mus'ab was defeated and killed by the Umayyad army led by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan at the Battle of Maskin.[8][20] At the time, al-Muhallab was engaged against the Azariqa in the environs of Ahwaz.[21] Upon hearing news of Abd al-Malik's victory and conquest of Iraq, al-Muhallab had his troops swear allegiance to the Umayyad caliph.[22] Abd al-Malik's kinsman and governor over Basra, Khalid ibn Abdallah, relieved al-Muhallab of command and assigned him to collect the kharaj (land tax) of Ahwaz.[1] The governor's brother, Abd al-Aziz, was appointed in al-Muhallab's place, but was routed by the Azariqa.[23] After Abd al-Malik was informed of his forces' defeat, he sent a letter reproaching Khalid for not utilizing al-Muhallab, "who is fortunate in judgment, good in management, skillful and experienced in war—a man of war, and the son of men of war".[24] Afterward, in 693/94, Abd al-Malik directly appointed al-Muhallab commander of the war against the Azariqa, but later that year, his troops deserted the field against them at Ramhormoz following news of the death of Bishr ibn Marwan, Khalid's replacement as governor of Basra.[1]

Toward the end of 694, Abd al-Malik appointed al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf governor over Iraq (Kufa and Basra) and the latter strongly backed al-Muhallab's campaign. With al-Hajjaj's support, he drove the Azariqa from Ahwaz into Fars as he had done previously and maintained the momentum against them until they withdrew further, into Kerman.[1][8] They barricaded themselves in Jiroft and split into two factions, one dominated by mawali which remained in Jiroft under the command of a certain Abd Rabbih al-Kabir, and the second, dominated by Arabs led by Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a, which headed north toward Tabaristan.[1][8] Al-Muhallab defeated Abd Rabbih's faction in Jiroft by 696,[1] killing them in their entirety.[8] During this time, he is credited with introducing iron stirrups on the saddles of his army's war horses,[25] in place of the wooden ones, which could barely withstand a rider's weight.[1] There is no known evidence that the horsemen of the ancient world used stirrups and literary sources indicate al-Muhallab's army was the first to use them during the fighting with the Kharijites in southern Persia.[26] Al-Muhallab's innovation would be used thenceforth by Muslim armies.[25] Qatari and his band were later defeated by Sufyan ibn Abrad al-Kalbi in 698/99.[27]

Umayyad governor of Khurasan and death

In 697/98, Khurasan was incorporated into al-Hajjaj's governorship and he appointed al-Muhallab as his deputy governor over the province.[1][28] The Kharijite rebellions had not taken root in Khurasan and at the time of his appointment, the Tamim formed the strongest army faction in the province.[29] According to historian Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban, al-Hajjaj viewed the unruly Tamim's dominance as the major impediment to his policies of centralization and expansion in the eastern half of the Caliphate. His solution was to balance the Tamim with the largely Azd–Rabi'a troops of al-Muhallab.[30] The latter's appointment marked a departure from the Umayyad tradition of appointing a member of the Quraysh as governor over Khurasan.[31]

By dint of his battlefield reputation and al-Hajjaj's resolute support, al-Muhallab secured the loyalty of the Khurasani troops.[32] He renewed their focus on the Muslim conquests in Transoxiana, which would serve as a means for the Azdi troops he brought from Iraq, and the longer-established Khurasani troops, to acquire war spoils.[25] Al-Muhallab began his term in 698 by preparing an army in the provincial capital of Merv, composed of his men from the campaigns against the Azariqa, Khurasani troops and local forces commanded by the mawali brothers Thabit and Hurayth ibn Qutba.[32] In 699, after leaving his son al-Mughira in charge of Merv, he led this army on an expedition to conquer Transoxiana.[32] To that effect, he captured the fortress of Zamm, a crossing point guarding the Oxus river, and recruited its ruler, who converted to Islam.[32]

After crossing the Oxus, al-Muhallab reached his main target, the fortress of Kish in Soghdia.[25][32] He besieged it for two years, despite counsels to abandon it and proceed deeper into Soghdia.[25] From his camp outside Kish, he often dispatched contingents commanded by his sons against neighboring areas, though their gains were negligible.[33] After news of his son al-Mughira's death in Merv in 701, he secured a tributary arrangement with Kish's defenders and withdrew toward the provincial capital.[33] While the traditional Muslim sources generally attribute his withdrawal to heartbreak over al-Mughira's death, al-Mada'ini notes that a conspiracy by troops of the Mudar (the alliance of the Tamim and Qays factions of the Basran and Khurasani armies) in his camp prompted him to abandon the war effort.[33] Shaban surmises that a combination of both factors, in addition to Tamimi infighting in al-Muhallab's camp and tensions emanating from the wide-scale revolt by the governor of Sistan, Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath, in 700, all led al-Muhallab to "return to Merv to put his own house in order before trying to make any advances in Transoxiana".[33] Ibn al-Ash'ath's forces swept westward through Fars and at one point gained control of Kufa and Basra before being stamped out by al-Hajjaj and his Syrian troops in 701. Al-Muhallab remained loyal to the Umayyads during the tumult.[1] He died at Marw al-Rudh, on the way to Merv, in 702.[33]

Legacy

The historian Hugh Kennedy describes al-Muhallab as "a figure of almost legendary prowess on the battlefield and a man with a great reputation as a commander", which he gained in "hard, unrewarding campaigning" against the Azariqa in the unfavorable terrain of Fars and Ahwaz.[25] According to Julius Wellhausen, though al-Muhallab's career in Khurasan "did not add to his renown in war", it brought about a development of "great importance" in the province: the influx of the Azd.[34] A small number of Azdi tribesmen had already been present, but it was only under al-Muhallab that the Azd gained prominence in Khurasan.[35] Together with their allies from the Rabi'a, they counted 21,000 soldiers out of the 40,000-strong Arab army of Khurasan,[36] and ended the previous dominance of the Tamim–Mudar alliance; a balance of power was thenceforth established, tilted only by support from the governor to either side.[37] Al-Muhallab was succeeded by his son Yazid as governor.[1] During this period, the Muslim conquest of Makran was consolidated and the Azd, the predominant Arab faction in this region, gained considerable wealth.[38] The Azd held al-Muhallab in high esteem and commemorated him and his accomplishments in legendary tales and song.[39]

The descendants of al-Muhallab and his father Abu Sufra, known as the Muhallabids, became a prominent family, "famed for their numbers and their remarkable role in early Islamic history" according to Crone.[40] They lost their fortunes with the death of their patron, Caliph Sulayman (r. 715–717), and several of them died during Yazid's abortive revolt against Caliph Yazid II (r. 720–724).[41] They later staged a comeback during the Third Muslim Civil War, during which they rebelled against the Umayyads, and many of their members held high office under various caliphs of the Abbasid dynasty, which had overthrown the Umayyads in 750.[42]

Notes

- Al-Muhallab's governorship of Mosul included jurisdiction over the Jazira, Arminiya and Adharbayjan.[1][2]

- Khurasan was attached to the Iraqi governorship of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, who appointed al-Muhallab as his deputy governor over Khurasan.

References

- Crone 1993, p. 357.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 110, 118.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 404, note 1.

- Strenziok 1960, p. 812.

- Wink 2002, p. 121.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 417.

- Hawting 1989, pp. 165–166.

- Rubinacci 1960, p. 810.

- Hawting 1989, p. 167.

- Hawting 1989, pp. 167–168.

- Hawting 1989, p. 168.

- Hawting 1989, p. 175.

- Hawting 1989, p. 172.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 86.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 87, 92.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 110, 118.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 110.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 123.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 133–134.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 198.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 182.

- Fishbein 1989, p. 199.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 200.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 202–203.

- Kennedy 2007, p. 243.

- Kennedy 2007, pp. 61, 243.

- Rubinacci 1960, pp. 810–811.

- Shaban 1971, p. 109.

- Shaban 1970, pp. 53–54.

- Shaban 1970, pp. 54–55.

- Shaban 1970, p. 54.

- Shaban 1970, p. 55.

- Shaban 1970, p. 56.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 427.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 427, note 2.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 427, note 3.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 427–428.

- Wink 2002, p. 53.

- Kennedy 2007, pp. 226, 243.

- Crone 1993, p. 358.

- Crone 1993, p. 359.

- Crone 1993, p. 358–359.

Bibliography

- Crone, P. (1993). "Al-Muhallab b. Abī Ṣufra". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 357. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Crone, P. (1993). "Muhallabids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 358–360. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Fishbein, Michael, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXI: The Victory of the Marwānids, A.D. 685–693/A.H. 66–73. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0221-4.

- Hawting, G.R., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XX: The Collapse of Sufyānid Authority and the Coming of the Marwānids: The Caliphates of Muʿāwiyah II and Marwān I and the Beginning of the Caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik, A.D. 683–685/A.H. 64–66. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-855-3.

- Hinds, Martin, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIII: The Zenith of the Marwānid House: The Last Years of ʿAbd al-Malik and the Caliphate of al-Walīd, A.D. 700–715/A.H. 81–95. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-721-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2007). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81585-0.

- Rubinacci, R. (1960). "Azārika". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 810–811. OCLC 495469456.

- Shaban, M. A. (1970). The Abbasid Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29534-3.

- Shaban, M. A. (1971). Islamic History: Volume 1, AD 600-750 (AH 132): A New Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08137-8.

- Strenziok, Gert (1960). "Azd". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 811–813. OCLC 495469456.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

- Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Boston and Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-391-04173-8.

| Preceded by Umayya ibn Abdallah |

Governor of Khurasan 697–702 |

Succeeded by Yazid ibn al-Muhallab |