Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prevents prosecutors from using a person's statements made in response to interrogation in police custody as evidence at their trial unless they can show that the person was informed of the right to consult with an attorney before and during questioning, and of the right against self-incrimination before police questioning, and that the defendant not only understood these rights, but voluntarily waived them.

| Miranda v. Arizona | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued February 28 – March 1, 1966 Decided June 13, 1966 | |

| Full case name | Miranda v. State of Arizona; Westover v. United States; Vignera v. State of New York; State of California v. Stewart |

| Citations | 384 U.S. 436 (more) 86 S. Ct. 1602; 16 L. Ed. 2d 694; 1966 U.S. LEXIS 2817; 10 A.L.R.3d 974 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendant . Superior Ct.; affirmed, 401 P.2d 721 (Ariz. 1965); cert. granted, 382 U.S. 925 (1965). |

| Subsequent | Retrial on remand, defendant convicted, Ariz. Superior Ct.; affirmed, 450 P.2d 364 (Ariz. 1969); rehearing denied, Ariz. Supreme Ct. March 11, 1969; cert. denied, 396 U.S. 868 (1969). |

| Holding | |

| The Fifth Amendment right against self incrimination requires law enforcement officials to advise a suspect interrogated in custody of their rights to remain silent and to obtain an attorney, at no charge if need be. Supreme Court of Arizona reversed and remanded. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by Black, Douglas, Brennan, Fortas |

| Concur/dissent | Clark |

| Dissent | Harlan, joined by Stewart, White |

| Dissent | White, joined by Harlan, Stewart |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amends. V, VI, XIV | |

Miranda was viewed by many as a radical change in American criminal law, since the Fifth Amendment was traditionally understood only to protect Americans against formal types of compulsion to confess, such as threats of contempt of court.[1] It has had a significant impact on law enforcement in the United States, by making what became known as the Miranda warning part of routine police procedure to ensure that suspects were informed of their rights. The Supreme Court decided Miranda with three other consolidated cases: Westover v. United States, Vignera v. New York, and California v. Stewart.

The Miranda warning (often shortened to "Miranda", or "Mirandizing" a suspect) is the name of the formal warning that is required to be given by law enforcement in the United States to criminal suspects in police custody (or in a custodial situation) before they are interrogated, in accordance with the Miranda ruling. The purpose of such is to ensure the accused are aware of, and reminded of, these rights before questioning or actions that are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response.

Pursuant to the U.S. Supreme Court decision Berghuis v. Thompkins (2010), criminal suspects who are aware of their right to silence and to an attorney, but choose not to "unambiguously" invoke them, may find any subsequent voluntary statements treated as an implied waiver of their rights, and used as or as part of evidence. At least one scholar has argued that Thompkins effectively gutted Miranda.[2]

Background

Legal

During the 1960s, a movement which provided defendants with legal aid emerged from the collective efforts of various bar associations.

In the civil realm, it led to the creation of the Legal Services Corporation under the Great Society program of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Escobedo v. Illinois, a case which closely foreshadowed Miranda, provided for the presence of counsel during police interrogation. This concept extended to a concern over police interrogation practices, which were considered by many to be barbaric and unjust. Coercive interrogation tactics were known in period slang as the "third degree".

Factual

On March 13, 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested by the Phoenix Police Department, based on circumstantial evidence linking him to the kidnapping and rape of an eighteen-year-old woman ten days earlier.[3] After two hours of interrogation by police officers, Miranda signed a confession to the rape charge on forms that included the typed statement: "I do hereby swear that I make this statement voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion, or promises of immunity, and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make may be used against me."[4]

However, at no time was Miranda told of his right to counsel. Before being presented with the form on which he was asked to write out the confession that he had already given orally, he was not advised of his right to remain silent, nor was he informed that his statements during the interrogation would be used against him. At trial, when prosecutors offered Miranda's written confession as evidence, his court-appointed lawyer, Alvin Moore, objected that because of these facts, the confession was not truly voluntary and should be excluded. Moore's objection was overruled, and based on this confession and other evidence, Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping. He was sentenced to 20–30 years of imprisonment on each charge, with sentences to run concurrently. Moore filed Miranda's appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court, claiming that Miranda's confession was not fully voluntary and should not have been admitted into the court proceedings. The Arizona Supreme Court affirmed the trial court's decision to admit the confession in State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d 721 (Ariz. 1965). In affirmation, the Arizona Supreme Court heavily emphasized the fact that Miranda did not specifically request an attorney.[5]

Attorney John Paul Frank, former law clerk to Justice Hugo Black, represented Miranda in his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.[6]

Supreme Court decision

On June 13, 1966, the Supreme Court issued a 5–4 decision in Miranda's favor that overturned his conviction and remanded his case back to Arizona for retrial.

Opinion of the Court

Five justices formed the majority and joined an opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren.[7] The Court ruled that because of the coercive nature of the custodial interrogation by police (Warren cited several police training manuals that had not been provided in the arguments), no confession could be admissible under the Fifth Amendment self-incrimination clause and Sixth Amendment right to an attorney unless a suspect has been made aware of his rights and the suspect has then waived them:

The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him.[8]

Thus, Miranda's conviction was overturned. The Court also made clear what must happen if a suspect chooses to exercise his or her rights:

If the individual indicates in any manner, at any time prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease ... If the individual states that he wants an attorney, the interrogation must cease until an attorney is present. At that time, the individual must have an opportunity to confer with the attorney and to have him present during any subsequent questioning.

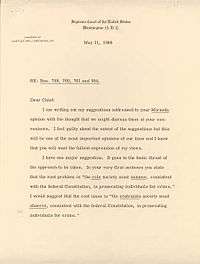

Warren also pointed to the existing procedures of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which required informing a suspect of his right to remain silent and his right to counsel, provided free of charge if the suspect was unable to pay. If the suspect requested counsel, "the interview is terminated." Warren included the FBI's four-page brief in his opinion.[9]

However, the dissenting justices accused the majority of overreacting to the problem of coercive interrogations, and anticipated a drastic effect. They believed that, once warned, suspects would always demand attorneys, and deny the police the ability to gain confessions.

Clark's concurrence in part, dissent in part

In a separate concurrence in part, dissent in part, Justice Tom C. Clark argued that the Warren Court went "too far too fast." Instead, Justice Clark would use the "totality of the circumstances" test enunciated by Justice Goldberg in Haynes v. Washington. Under this test, the court would:

consider in each case whether the police officer prior to custodial interrogation added the warning that the suspect might have counsel present at the interrogation and, further, that a court would appoint one at his request if he was too poor to employ counsel. In the absence of warnings, the burden would be on the State to prove that counsel was knowingly and intelligently waived or that in the totality of the circumstances, including the failure to give the necessary warnings, the confession was clearly voluntary.

Harlan's dissent

In dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote that "nothing in the letter or the spirit of the Constitution or in the precedents squares with the heavy-handed and one-sided action that is so precipitously taken by the Court in the name of fulfilling its constitutional responsibilities." Harlan closed his remarks by quoting former Justice Robert H. Jackson: "This Court is forever adding new stories to the temples of constitutional law, and the temples have a way of collapsing when one story too many is added."

White's dissent

Justice Byron White took issue with the court having announced a new constitutional right when it had no "factual and textual bases" in the Constitution or previous opinions of the Court for the rule announced in the opinion. He stated: "The proposition that the privilege against self-incrimination forbids in-custody interrogation without the warnings specified in the majority opinion and without a clear waiver of counsel has no significant support in the history of the privilege or in the language of the Fifth Amendment." White did not believe the right had any basis in English common law.

White further warned of the dire consequences of the majority opinion:

I have no desire whatsoever to share the responsibility for any such impact on the present criminal process. In some unknown number of cases, the Court's rule will return a killer, a rapist or other criminal to the streets and to the environment which produced him, to repeat his crime whenever it pleases him. As a consequence, there will not be a gain, but a loss, in human dignity.

Subsequent developments

Retrial

Miranda was retried in 1967 after the original case against him was thrown out. This time the prosecution, instead of using the confession, introduced other evidence and called witnesses. One witness was Twila Hoffman, a woman with whom Miranda was living at the time of the offense; she testified that he had told her of committing the crime.[10][11] Miranda was convicted in 1967 and sentenced to serve 20 to 30 years.[11] The Supreme Court of Arizona affirmed,[12] and the United States Supreme Court denied review.[13] Miranda was paroled in 1972. After his release, he returned to his old neighborhood and made a modest living autographing police officers' "Miranda cards" that contained the text of the warning for reading to arrestees. Miranda was stabbed to death during an argument in a bar on January 31, 1976.[14] A suspect was arrested, but due to a lack of evidence against him, he was released.[15]

Another three defendants whose cases had been tied in with Miranda's – an armed robber, a stick-up man, and a bank robber – either made plea bargains to lesser charges or were found guilty again despite the exclusion of their confessions.[16]

Reaction

The Miranda decision was widely criticized when it came down, as many felt it was unfair to inform suspected criminals of their rights, as outlined in the decision. Richard Nixon and other conservatives denounced Miranda for undermining the efficiency of the police, and argued the ruling would contribute to an increase in crime. Nixon, upon becoming President, promised to appoint judges who would reverse the philosophy he viewed as "soft on crime." Many supporters of law enforcement were angered by the decision's negative view of police officers.[17]

Miranda warning

After the Miranda decision, the nation's police departments were required to inform arrested persons or suspects of their rights under the ruling prior to custodial interrogation.[18] Such information is called a Miranda warning. Since it is usually required that the suspects be asked if they understand their rights, courts have also ruled that any subsequent waiver of Miranda rights must be knowing, intelligent, and voluntary.[19]

Many American police departments have pre-printed Miranda waiver forms that a suspect must sign and date (after hearing and reading the warnings again) if an interrogation is to occur.[20][21]

Data from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports shows a sharp reduction in the clearance rate of violent and property crimes after Miranda.[22] However, according to other studies from the 1960s and 1970s, "contrary to popular belief, Miranda had little, if any, effect on detectives' ability to solve crimes."[11]

Legal developments

The federal Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 purported to overrule Miranda for federal criminal cases and restore the "totality of the circumstances" test that had prevailed previous to Miranda.[23] The validity of this provision of the law, which is still codified at 18 U.S.C. § 3501, was not ruled on for another 30 years because the Justice Department never attempted to rely on it to support the introduction of a confession into evidence at any criminal trial.

Miranda was undermined by several subsequent decisions that seemed to grant exceptions to the Miranda warnings, challenging the ruling's claim to be a necessary corollary of the Fifth Amendment. The exceptions and developments that occurred over the years included:

- The Court found in Harris v. New York, 401 U.S. 222 (1971), that a confession obtained in violation of the Miranda standards may nonetheless be used for purposes of impeaching the defendant's testimony; that is, if the defendant takes the stand at trial and the prosecution wishes to introduce the defendant's confession as a prior inconsistent statement to attack the defendant's credibility, the Miranda holding will not prohibit this.

- The Court found in Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291 (1980), that a "spontaneous" statement made by a defendant while in custody, even though the defendant has not been given the Miranda warnings or has invoked the right to counsel and a lawyer is not yet present, is admissible in evidence, as long as the statement was not given in response to police questioning or other conduct by the police likely to produce an incriminating response.

- The Court found in Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420 (1984), that a person subjected to custodial interrogation is entitled to the benefit of the procedural safeguards enunciated in Miranda, regardless of the nature or severity of the offense of which he is suspected or for which he was arrested.

- The Court found in New York v. Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984), that there is also a "public safety" exception to the requirement that Miranda warnings be given before questioning; for example, if the defendant is in possession of information regarding the location of an unattended gun or there are other similar exigent circumstances that require protection of the public, the defendant may be questioned without warning and his responses, though incriminating, will be admissible in evidence. In 2009, the California Supreme Court upheld the conviction of Richard Allen Davis, finding that the public-safety exception applied despite the fact that 64 days had passed from the disappearance of the girl later found to be murdered.[24]

- The Court found in Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157 (1986), that the words "knowing, intelligent, and voluntary" mean only that suspects reasonably appear to understand what they are doing and are not being coerced into signing the waiver; the Court ruled that it is irrelevant whether the suspect may actually have been cognitively or mentally impaired at the time.

United States v. Garibay (1998) clarified an important matter regarding the scope of Miranda. Defendant Jose Garibay barely spoke English and clearly showed a lack of understanding; indeed, "the agent admitted that he had to rephrase questions when the defendant appeared confused."[25] Because of the defendant's low I.Q. and poor English-language skills, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that it was a "clear error" when the district court found that Garibay had "knowingly and intelligently waived his Miranda rights." The court investigated his waiver and discovered that it was missing all items for which they were looking: he never signed a waiver, he only received his warnings verbally and in English, and no interpreter was provided although they were available. With an opinion that stressed "the requirement that a defendant 'knowingly and intelligently' waive his Miranda rights," the Court reversed Garibay's conviction and remanded his case.[26]

Miranda survived a strong challenge in Dickerson v. United States, 530 U.S. 428 (2000), when the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda through § 3501 was tested. At issue was whether the Miranda warnings were actually compelled by the Constitution, or were rather merely measures enacted as a matter of judicial policy. In Dickerson, the Court, speaking through Chief Justice Rehnquist, upheld Miranda 7–2 and stated that "the warnings have become part of our national culture". In dissent, Justice Scalia argued that Miranda warnings were not constitutionally required. He cited several cases demonstrating a majority of the then-current court, counting himself, and Justices Kennedy, O'Connor, and Thomas, as well as Rehnquist (who had just delivered a contrary opinion), "[were] on record as believing that a violation of Miranda is not a violation of the Constitution."

Over time, interrogators began to devise techniques to honor the "letter" but not the "spirit" of Miranda. In the case of Missouri v. Seibert, 542 U.S. 600 (2004), the Supreme Court halted one of the more controversial practices. Missouri police had been deliberately withholding Miranda warnings and questioning suspects until they obtained confessions, then providing the warnings, getting waivers, and eliciting confessions again. Justice Souter wrote for the plurality: "Strategists dedicated to draining the substance out of Miranda cannot accomplish by training instructions what Dickerson held Congress could not do by statute."[27]

Berghuis v. Thompkins (2010) was a ruling in which the Supreme Court held that a suspect's "ambiguous or equivocal" statement, or lack of statements, does not mean that police must end an interrogation.[28] At least one scholar has argued that Thompkins effectively gutted Miranda. In The Right to Remain Silent, Charles Weisselberg wrote that "the majority in Thompkins rejected the fundamental underpinnings of Miranda v. Arizona's prophylactic rule and established a new one that fails to protect the rights of suspects" and that

But in Thompkins, neither Michigan nor the Solicitor General were able to cite any decision in which a court found that a suspect had given an implied waiver after lengthy questioning. Thompkins persevered for almost three hours before succumbing to his interrogators. In finding a waiver on these facts, Thompkins gives us an implied waiver doctrine on steroids.[2]

Effect on law enforcement

Miranda’s impact on law enforcement remains in dispute. Many legal scholars believe that police have adjusted their practices in response to Miranda and that its mandates have not hampered police investigations.[29] Others argue that the Miranda rule has resulted in a lower rate of conviction,[30] with a possible reduction in the rate of confessions of between four and sixteen percent.[31] Some scholars argue that Miranda warnings have reduced the rate at which the police solve crimes,[32] while others question their methodology and conclusions.[33]

See also

References

- Saltzburg & Capra (2018), p. 761.

- Charles Weisselberg and Stephanos Bibas, The Right to Remain Silent, 159 U. Pa. L. Rev. PENNumbra 69 (2010), Available at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/facpubs/2181 (Retrieved May 2, 2016)

- Miranda also matched the description given by a robbery victim of the perpetrator in a robbery several months earlier. He was simultaneously interrogated about both of these crimes, confessed to both, but was not asked to and did not write down his confession to the robbery. He was separately tried and convicted of the robbery and sentenced to 20 to 25 years of imprisonment. This crime, trial, and sentence is separate from the rape-kidnapping case appealed to the Supreme Court.

- Michael S. Lief and H. Mitchell Caldwell "'You Have the Right to Remain Silent,'" American Heritage, August/September 2006.

- Miranda's oral confession in the robbery case was also appealed and the Arizona Supreme Court likewise affirmed the trial decision to admit it in State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d 716. This case was not part of the appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States.

- Oliver, Myrna (September 12, 2002). "John P. Frank, 84; Attorney Won Key Decision in 1966 Miranda Case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- LaFave et al. (2015), § 6.5(b).

- Syllabus to the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miranda v. Arizona, holding 1.(d).

- Willing, Richard (June 10, 2016). "The right to remain silent, brought you by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI". The Washington Post.

- State v. Miranda, 104 Ariz. 174, 176, 450 P.2d 364, 366 (1969).

- Lief, Michael S.; H. Mitchell Caldwell (Aug–Sep 2006). "You Have The Right To Remain Silent". American Heritage. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- State v. Miranda, 104 Ariz. 174, 450 P.2d 364 (1969)

- 396 U.S. 868 (1969).

- "Miranda Slain; Main Figure in Landmark Suspects' Rights Case". The New York Times. February 1, 1976. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Charles Montaldo, Miranda Rights and Warning: Landmark Case Evolved from 1963 Ernesto Miranda Arrest, about.com; accessed 13 June 2014.

- "The Law: Catching Up with Miranda". Time. March 3, 1967. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "The Miranda Decision: Criminal Wrongs, Citizen Rights". The Washington Post. August 7, 1983. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "What Are Your Miranda Rights". ExpertLaw. 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- See, e.g., "Colorado v. Spring, 479 U.S. 564, 856-57 (1987)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Edwards, H. Lynn (1966). "The Effects of Miranda on the Work of the Federal Bureau of Investigation". American Criminal Law Quarterly. 159: 160–161. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Miranda Waiver" (PDF). University Police Department. University of North Alabama. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Handcuffing the Cops: Miranda's Harmful Effects on Law Enforcement | NCPA". 2015-05-18. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2016-09-28.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Cite Miranda And Go Free". Sarasota Journal. 31 May 1968. p. 7.

- People vs. Davis, S056425.

- Einesman, Floralynn (1999). "Confessions and Culture: The Interaction of Miranda and Diversity". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 90 (1): 1–48 [p. 41]. doi:10.2307/1144162. JSTOR 1144162. NCJ 182327.

- United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit (May 5, 1998), UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Jose Rosario GARIBAY, Jr., Defendant-Appellant. No. 96-50606., retrieved February 15, 2017

- "Missouri v. Seibert, section VI". Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-07. Hosted by Duke University School of Law.

- Berghuis v. Thompkins, 560 U.S. 370 (2010).

- Duke, Steven B. (2007). "Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?". Chapman Law Review. 10 (3): 551. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Cassell, Paul G. (19 August 2011). "Miranda's Social Costs: An Empirical Reassessment". Northwestern University Law Review. 90 (2). Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Fairness and effectiveness in policing : the evidence. National Academies Press. 2004. ISBN 0309084334.

- Cassell, Paul G.; Fowles, Richard (2017). "Still Handcuffing the Cops: A Review of Fifty Years of Empirical Evidence of Miranda's Harmful Effects on Law Enforcement". Brigham Young Law Review. 97: 685. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Alschuler, Albert W. (2017). "Miranda's Fourfold Failure". Boston Law Review. 97: 649. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- LaFave, Wayne R.; Israel, Jerold H.; King, Nancy J.; Kerr, Orin S. (2015). Criminal Procedure (4th ed.). St. Paul: West Academic Publishing. OCLC 934517477.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saltzburg, Stephen A.; Capra, Daniel J. (2018). American Criminal Procedure: Cases and Commentary (11th ed.). St. Paul: West Academic. ISBN 978-1683289845.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Baker, Liva (1983). Miranda: Crime, law, and politics. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-11240-9.

- Kassin, Saul M.; Norwick, Rebecca J. (2004). "Why People Waive Their Miranda Rights: The Power of Innocence". Law and Human Behavior. 28 (2): 211–221. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.983. doi:10.1023/B:LAHU.0000022323.74584.f5.

- Levy, Leonard W. (1986) [1969]. Origins of the Fifth Amendment (Reprint ed.). New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-919580-2.

- Soltero, Carlos R. (2006). "Miranda v. Arizona (1966) and the rights of the criminally accused". Latinos and American Law: Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 61–74. ISBN 978-0-292-71411-3.

- Stuart, Gary L. (2004). Miranda: The Story of America's Right to Remain Silent. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2313-9.

External links

- Text of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

- "Supreme Court Landmark Case Miranda v. Arizona" from C-SPAN's Landmark Cases: Historic Supreme Court Decisions

- An online publication titled "Miranda v. Arizona: The Rights to Justice" containing the most salient documents and other primary and secondary sources from the Law Library of Congress