Undertale

Undertale is a role-playing video game created by indie developer Toby Fox. The player controls a child who has fallen into the Underground: a large, secluded region under the surface of the Earth, separated by a magic barrier. The player meets various monsters during the journey back to the surface. Some monsters might engage the player in a fight. The combat system involves the player navigating through mini-bullet hell attacks by the opponent. They can opt to pacify or subdue monsters in order to spare them instead of killing them. These choices affect the game, with the dialogue, characters, and story changing based on outcomes.

| Undertale | |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Toby Fox[lower-alpha 1] |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Designer(s) | Toby Fox |

| Artist(s) | Temmie Chang |

| Composer(s) | Toby Fox |

| Engine | GameMaker Studio |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | September 15, 2015

|

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Outside of some artwork, Fox developed the entirety of the game by himself, including the script and music. The game took inspiration from several sources. These include the Mother, Brandish, and Mario & Luigi role-playing series, the bullet hell shooter series Touhou Project, and the British comedy show Mr. Bean. Originally, Undertale was meant to be two hours in length and was set to be released in mid-2014. However, development was delayed over the next three years.

The game was released for Microsoft Windows and OS X in September 2015. It was also ported to Linux in July 2016, PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita in August 2017, and the Nintendo Switch in September 2018. The game was acclaimed for its thematic material, intuitive combat system, musical score, originality, story, dialogue, and characters. The game sold over one million copies and was nominated for multiple accolades and awards. Several gaming publications and conventions listed Undertale as game of the year. The first chapter of a related game, Deltarune, was released in October 2018.

Gameplay

Undertale is a role-playing game that uses a top-down perspective.[3] In the game, players control a child and complete objectives in order to progress through the story.[4] Players explore an underground world filled with towns and caves, and are required to solve numerous puzzles on their journey.[4][5] The underground world is the home of monsters, many of whom challenge the player in combat;[5] players decide whether to kill, flee, or befriend them.[4][6] Choices made by the player radically affect the plot and general progression of the game, with the player's morality acting as the cornerstone for the game's development.

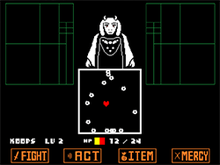

When players encounter enemies in either scripted events or random encounters, they enter a battle mode. During battles, players control a small heart which represents their soul, and must avoid attacks unleashed by the opposing monster similar to a bullet hell shooter.[4][5] As the game progresses, new elements are introduced, such as colored obstacles, and boss battles which change the way players control the heart.[7] Players may choose to attack the enemy, which involves timed button presses. Killing enemies will cause the player to earn EXP (in turn increasing their LOVE) and gold.[8] They can use the ACT option to check an enemy's attacking and defending attributes as well as perform various other actions, which vary depending on the enemy.[4] If the player uses the right actions to respond to the enemy, or attacks them until they have low HP (but still alive) they can choose to spare them and end the fight without killing them.[9] For some boss encounters to be completed peacefully, the player is required to survive until the character they are facing has finished their dialogue. The game features multiple story branches and endings depending on whether players choose to kill or spare their enemies; and as such, it is possible to clear the game without killing a single enemy.[10]

Monsters will talk to the player during the battle, and the game will tell the players what the monster's feelings and actions are.[11] Enemy attacks change based on how players interact with them: should players choose non-violent options, enemy attacks are easy, whereas they become difficult if players choose violent options.[5][11] The game relies on a number of metafictional elements in both its gameplay and story.[12] When players participate in a boss battle on a second playthrough, the dialogue will be altered depending on actions in previous playthroughs.[13]

Plot

Undertale takes place in the Underground, a realm to where monsters, once equal to humans, were banished after war broke out between them. The Underground is sealed from the surface world by an imperfect magic barrier, the only point of entry being at Mount Ebott.[14] A human child falls into the Underground and encounters Flowey, a sentient flower who teaches them the game's mechanics and encourages them to raise their "LV", or "LOVE", by gaining "EXP" through killing monsters.[lower-alpha 4] When Flowey attempts to murder the human to take their soul for himself, the human is rescued by Toriel, a motherly goat-like monster, who teaches the human to solve puzzles and survive conflict in the Underground without killing. She intends to adopt the human, wanting to protect them from Asgore Dreemurr, the king of the Underground.

The human eventually leaves Toriel to search for Asgore's castle, which contains the barrier leading to the surface world. Along the way, the human encounters several monsters, including the skeletons Sans and Papyrus, two brothers who act as sentries for the Snowdin forest; Undyne, the head of the royal guard; Alphys, the kingdom's royal scientist; and Mettaton, a robotic television host Alphys created. Some of them are fought, with the human having to choose whether to kill them or to show mercy; should the human spare them, they may choose to become friends. During their travels, the human learns the cause of the war between humans and monsters. Asriel, the son of Asgore and Toriel, befriended the first human child who fell into the Underground and was adopted by Asgore and Toriel. One day, the child killed themselves by eating poisonous flowers. When Asriel returned their body to the humans, they attacked and fatally wounded him, resulting in Asgore declaring war. Asgore now seeks to break the barrier, which requires him to collect seven human souls, of which he has six.

The game's ending depends on how the player resolved encounters with monsters.[10][lower-alpha 5] If the player killed some but not all monsters, the human arrives at Asgore's castle and learns that they also need a monster's soul to cross the barrier, forcing them to fight Asgore. Sans stops the human before their confrontation, revealing that the human's "LOVE" is an acronym for "level of violence" and "EXP" for "execution points." Sans judges the human based on the combined resolution of the encounters. The human fights Asgore, but Flowey interrupts them, killing Asgore and stealing the human souls. With the aid of the rebelling souls, the human defeats Flowey, falls unconscious, and awakens on the human side of the barrier; they receive a phone call from Sans, explaining the state of the Underground after the human's departure. This ending is referred to as the "Neutral" ending, and has many different epilogue phone calls depending on how many monsters have been killed and who the player has spared.

If the player instead kills no monsters and has completed a previous (passive neutral) playthrough of the game,[17] Flowey is revealed to be a reincarnation of Asriel, created as part of Alphys's experiments. Toriel intervenes before the human fights Asgore and is joined by the other monsters the human has befriended. Flowey ambushes the group, re-taking all the human souls and the souls of all the monsters to take an older Asriel's form to fight the human. The human connects with their new friends during the fight, eventually triumphing. Asriel reverts to his child form, destroys the barrier, and expresses his remorse to the others before leaving. The human falls unconscious and is awoken to see their friends surrounding them, with the knowledge of the human's name – Frisk. The monsters reintegrate with the humans on the surface, while Frisk has the option of accepting Toriel as their adoptive mother. This route is referred to as the "Pacifist" or "True Pacifist" route.

Another ending ensues if the player kills all monsters -known as the "Genocide" route-[13][17] in which Frisk becomes influenced by Chara, the fallen human child whose body Asriel attempted to return. When Frisk reaches Asgore's castle, Sans attempts to stop them, but Frisk kills him. Flowey kills Asgore in an attempt to get mercy, but Frisk executes Flowey anyway. The fallen human child assumes control and, with or without the player's consent, destroys the universe. To enable further replays of the game, Frisk must first give their soul to the fallen human child in exchange for restoring the universe, which will permanently alter every subsequent Pacifist run.

Development

Undertale was developed by Toby Fox across 32 months.[18] Development was financed through a crowdfunding campaign on the website Kickstarter. The campaign was launched on June 25, 2013 with a goal of US$5,000; it ended on July 25, 2013, with US$51,124 raised by 2,398 people (1022.48% of the original goal).[19] Undertale's creation ensued after Fox created a battle system using the game creation system GameMaker: Studio.[20] He wanted to develop a role-playing game that was different from the traditional design, which he often found "boring to play".[21] He set out to develop a game with "interesting characters", and that "utilizes the medium as a storytelling device ... instead of having the story and gameplay abstractions be completely separate".[21]

Fox worked on the entire game independently, besides some of the art; he decided to work independently to avoid relying on others.[18] Fox had little experience with game development; he and his three brothers often used RPG Maker 2000 to make role-playing games, though few were ever completed. Fox also worked on several EarthBound ROM hacks while in high school.[21] Temmie Chang worked as the main artistic assistant for the game, providing most of the sprites and concept art.[22][23] Fox has said that the game's art style would likely remain the same if he had access to a larger team of artists. He found that "there's a psychological thread that says audiences become more attached to characters drawn simply rather than in detail", particularly benefiting from the use of visual gags within the art.[24]

Game design

The defensive segment within the battle system was inspired by the Mario & Luigi series, as well as bullet hell shooters such as the Touhou Project series.[25] When working on the battle system, Fox set out to create a mechanic that he would personally enjoy.[26] He wanted Undertale to have a battle system equally engaging as Super Mario RPG (1996) and Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga (2003). Fox did not want grinding to be necessary at any point in the game, instead leaving it optional to players. He also did not wish to introduce fetch quests, as they involve backtracking, which he dislikes.[18] In terms of the game's difficulty, Fox ensured that it was easy and enjoyable. He asked some friends who are inexperienced with bullet hell shooters to test the game, and found that they were able to complete it. He felt that the game's difficulty is optimal, particularly considering the complications involved in adding another difficulty setting.[27]

The game's dialogue system was inspired by Shin Megami Tensei (1992),[25] particularly the gameplay mechanic whereby players can talk to monsters to avoid conflict. Fox intended to expand upon this mechanic, as failing to negotiate resulted in a requirement to fight. "I want to create a system that satisfied my urge for talking to monsters," he said.[5] When he began developing this mechanic, the concept of completing the game without killing any enemies "just evolved naturally".[28] However, he never considered removing the option to fight throughout development.[28] When questioned on the difficulty of playing the game without killing, Fox responded that it is "the crux of one of the major themes of this game", asking players to think about it themselves.[28] Certain parts of the game, such as the "CORE" area, as well as the plot pace and progression of the game and minor references, draw strong parallels with Chrono Trigger.

Writing

According to Fox, the "idea of being trapped in an underground world" was inspired by the video game Brandish.[23] Fox was partly influenced by the silliness of internet culture, as well as comedy shows like Mr. Bean.[18] He was also inspired by the unsettling atmosphere of EarthBound.[18] Fox's desire to "subvert concepts that go unquestioned in many games" further influenced Undertale's development.[28] Fox found that the writing became easier after establishing a character's voice and mood. He also felt that creating the world was a natural process, as it expressed the stories of those within it.[24] Fox felt the importance to make the game's monsters "feel like an individual".[25] He cited the Final Fantasy series as the opposite; "all monsters in RPGs like Final Fantasy are the same ... there's no meaning to that".[25]

The character of Toriel, who is one of the first to appear in the game, was created as a parody of tutorial characters. Fox strongly disliked the use of the companion character Fi in The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword, in which the answers to puzzles were often revealed early. Fox also felt that role-playing video games generally lack mother characters; in the Pokémon series, as well as Mother and EarthBound, Fox felt that the mothers are used as "symbols rather than characters".[21] In response, Fox intended for Toriel's character to be "a mom that hopefully acts like a mom", and "genuinely cares" about players' actions.[21]

Music

The game's soundtrack was entirely composed by Fox. A self-taught musician, he composed most of the tracks with little iteration; the game's main theme, "Undertale", was the only song to undergo multiple iterations in development. The soundtrack was inspired by music from Super NES role-playing games,[18] such as EarthBound,[31] as well as the webcomic Homestuck, for which Fox provided some of the music.[18] Fox also stated that he tries to be inspired by all music he listens to,[26] particularly those in video games.[31] According to Fox, over 90% of the songs were composed specifically for the game.[20] "Megalovania", the song used during the boss battle with Sans, had previously been used within Homestuck and in one of Fox's EarthBound ROM hacks.[30][32] For each section of the game, Fox composed the music prior to programming, as it helped "decide how the scene should go".[20] He initially tried using a music tracker to compose the soundtrack, but found it difficult to use. He ultimately decided to play segments of the music separately, and connect them on a track.[31] To celebrate the one year anniversary of the game, Fox released five unused musical works on his blog in 2016.[33] Four of the game's songs were released as official downloadable content for the Steam version of Taito's Groove Coaster.[32]

Undertale's soundtrack has been well received by critics as part of the success of the game, in particular for its use of various leitmotifs for the various characters used throughout various tracks.[34][35] In particular, "Hopes and Dreams", the boss theme when fighting Asriel in the run-through where the player avoids killing any monster, brings back most of the main character themes, and is "a perfect way to cap off your journey", according to USgamer's Nadia Oxford.[30] Oxford notes this track in particular demonstrates Fox's ability at "turning old songs into completely new experiences", used throughout the game's soundtrack.[30] Tyler Hicks of GameSpot compared the music to "bit-based melodies".[36]

Release

The game was released on September 15, 2015, for Microsoft Windows and OS X,[37] and on July 17, 2016, for Linux.[38] Fox expressed interest in releasing Undertale on other platforms, but was initially unable to port it to Nintendo platforms without reprogramming the game due to the engine's lack of support for these platforms.[18] A patch was released in January 2016, fixing bugs and altering the appearance of blue attacks to help colorblind players see them better.[39] Sony Interactive Entertainment announced during E3 2017 that Undertale would get a release for the PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita, a Japanese localization, and a retail version published by Fangamer. These versions were released on August 15, 2017.[40][41][42] A Nintendo Switch version was revealed during a March 2018 Nintendo Direct, though no release date was given at the time;[43][44] Undertale's release on Switch highlighted a deal made between Nintendo and YoYo Games to allow users of GameMaker Studio 2 to directly export their games to the Switch.[45] The Switch version was released on September 15, 2018, in Japan,[46] and on September 18, 2018, worldwide.[47] All the console ports were developed and published by Japanese localizer 8-4 in all regions.[1][2]

Other Undertale media and merchandise have been released, including toy figurines and plush toys based on characters from the game.[48] The game's official soundtrack was released by video game music label Materia Collective in 2015, simultaneously with the game's release.[49] Additionally, two official Undertale cover albums have been released: the 2015 metal/electronic album Determination by RichaadEB and Ace Waters,[50][51] and the 2016 jazz album Live at Grillby's by Carlos Eiene, better known as insaneintherainmusic.[52] Another album of jazz duets based on Undertale's songs, Prescription for Sleep, was performed and released in 2016 by saxophonist Norihiko Hibino and pianist Ayaki Sato.[53] A 2xLP vinyl edition of the Undertale soundtrack, produced by iam8bit, was also released in the same year.[54] Two official UNDERTALE Piano Collections sheet music books and digital albums, arranged by David Peacock and performed by Augustine Mayuga Gonzales, were released in 2017 and 2018[55][56] by Materia Collective. A Mii Fighter costume based on Sans was made available for download in the crossover title Super Smash Bros. Ultimate in September 2019, marking the character's official debut as a 3D model. This costume also adds a new arrangement of "Megalovania" by Fox as a music track.[57] Super Smash Bros. director Masahiro Sakurai noted that Sans was a popular request to appear in the game.[58] Music from Undertale was also added to Taiko no Tatsujin: Drum 'n' Fun! as downloadable content.[59]

Deltarune

After previously teasing something Undertale-related a day earlier, Fox released the first chapter of Deltarune on October 31, 2018, for Windows and macOS for free.[60] Deltarune is "not the world of Undertale", according to Fox, though characters and settings may bring some of Undertale's world to mind,[61] and is "intended for people who have completed Undertale";[62] the name Deltarune is an anagram of Undertale.[63] Fox stated that this release is the first part of a new project, and considered the release a "survey program" to determine how to take the project further.[63] Fox clarified that Deltarune will be a larger project than Undertale; Fox stated it took him a few years to create the first chapter of Deltarune, much longer than it took him to complete the Undertale demo. Because of the larger scope, he anticipates getting a team to help develop Deltarune, and has no anticipated timetable when it will be completed. Once the game is ready, Fox will release the game as one whole package.[61] Fox plans for Deltarune to have only one ending, regardless of what choices the player makes in the game.[61]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Undertale received critical acclaim, and was quickly considered a cult video game by numerous publications.[72][73] Review aggregator Metacritic calculated an average score of 92 out of 100, based on 43 reviews.[64] Metacritic ranks the game the third-highest rated Windows game released in 2015,[64] and among the top 50 of all time.[74] Praise was particularly directed at the game's writing, unique characters, and combat system. GameSpot's Tyler Hicks declared it "one of the most progressive and innovative RPGs to come in a long time",[36] and IGN's Kallie Plagge called it "a masterfully crafted experience".[16] By the end of 2015, in a preliminary report by Steam Spy, Undertale was one of the best-selling games on Steam, with 530,343 copies sold.[75] By early February 2016, the game surpassed one million sales,[76] and by July 2018, the game had an estimated total of three and a half million players on Steam.[77] Japanese digital PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita sales surpassed 100,000 copies sold by February 2018.[78]

Daniel Tack of Game Informer called the game's combat system "incredibly nuanced", commenting on the uniqueness of each enemy encounter.[68] Giant Bomb's Austin Walker praised the complexity of the combat, commenting that it is "unconventional, clever, and occasionally really difficult".[69] Ben "Yahtzee" Croshaw of The Escapist commended the game's ability to blend "turn-based and live combat elements in a way that actually fucking works".[79] IGN's Plagge praised the ability to avoid combat, opting for friendly conversations instead.[16] Jesse Singal of The Boston Globe found the game's ability to make the player empathize with the monsters during combat if they opted for non-violent actions was "indicative of the broader, fundamental sweetness at the core" of Undertale.[80]

Reviewers praised the game's writing and narrative, with IGN's Plagge calling it "excellent".[16] The Escapist's Croshaw considered Undertale the best-written game of 2015, writing that "is on the one hand hilarious... and is also, by the end, rather heartfelt".[79] Destructoid's Ben Davis praised the game's characters and use of comedy, and compared its tone, characters, and storytelling to Cave Story (2004).[4] PC Gamer's Richard Cobbett provided similar comments, writing that "even its weaker moments... just about work".[70]

The game's visuals received mixed reactions. Giant Bomb's Walker called it "simple, but communicative".[69] IGN's Plagge wrote that the game "isn't always pretty" and "often ugly", but felt that the music and animations compensate.[16] The Escapist's Croshaw remarked that "it wobbles between basic and functional to just plain bad".[79] Other reviewers liked the graphics: Daniel Tack of Game Informer felt that the visuals appropriately match the characters and settings,[68] while Richard Cobbett of PC Gamer commended the ability of the visuals to convey emotion.[70]

About a year after release, Fox commented that he was surprised by how popular the game had become and though appreciative of the attention, he found it stressful. Fox said: "It wouldn't surprise me if I never made a game as successful again. That's fine with me though."[81]

Accolades

The game appeared on several year-end lists of the best games of 2015, receiving Game of the Month and Funniest Game on PC from Rock, Paper, Shotgun,[82][83] Best Game Ever from GameFAQs,[84] and Game of the Year for PC from The Jimquisition,[85] Zero Punctuation,[86] and IGN.[87] It also received Best PC Game from Destructoid,[88] the Matthew Crump Cultural Innovation Award[89] and Most Fulfilling Crowdfunded Game from the SXSW Gaming Awards;[89] and Game, Original Role Playing from the National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers awards.[90]

Undertale garnered awards and nominations in a variety of categories with praise for its story, narrative and for its role-playing. At the IGN's Best of 2015, the game received Best Story.[91] Undertale was nominated for the Innovation Award, Best Debut, and Best Narrative at the Game Developers Choice Awards.[92] In 2016, at the Independent Games Festival the game won the Audience Award, and garnered three nominations for Excellence in Audio, Excellence in Narrative, and the Seumas McNally Grand Prize.[93][94] The SXSW Gaming Awards named it the Most Fulfilling Crowdfunded Game, and awarded it the Matthew Crump Cultural Innovation Award.[89] The same year at the Steam Awards the game received a nomination for The "I'm not crying, there's just something in my eye" award.[95] Polygon named the game among the decade's best.[96]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Result | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12th British Academy Games Awards | 7 April 2016 | Story | Nominated | [97][98] |

| 19th Annual D.I.C.E. Awards | 18 February 2016 | Outstanding Achievement in Game Direction | Nominated | [99] |

| DICE Sprite Award | Nominated | |||

| Role-Playing/Massive Multiplayer Game of the Year | Nominated | |||

| Dragon Awards | 11 August 2016 | Best Science Fiction or Fantasy PC/Console Game | Nominated | [100] |

| Global Game Awards | 27 November 2015 | Best Indie | Runner-up | [101] |

| The Game Awards | 3 December 2015 | Best Independent Game | Nominated | [102] |

| Games for Change | Nominated | |||

| Best Role-Playing Game | Nominated | |||

| 2016 Game Developers Choice Awards | 16 March 2016 | Innovation Award | Nominated | [92] |

| Best Debut | Nominated | |||

| Best Narrative | Nominated | |||

| 2016 Independent Games Festival Awards | Seumas McNally Grand Prize | Nominated | [103] | |

| Excellence in Audio | Nominated | |||

| Excellence in Narrative | Nominated | |||

| Audience Award | Won | [93] | ||

| 2016 SXSW Gaming Awards | 19 March 2016 | Game of the Year | Nominated | [104] |

| Excellence in Gameplay | Nominated | |||

| Most Promising New Intellectual Property | Nominated | |||

| Most Fulfilling Crowdfunded Game | Won | [89] | ||

| Matthew Crump Cultural Innovation Award | Won | |||

| NAVGTR Awards | 21 March 2016 | Game, Original Role Playing | Won | [90] |

| Original Light Mix Score, New IP | Nominated | |||

| Game Design, New IP | Nominated |

See also

- List of GameMaker Studio games

Notes

- 8-4 developed the console versions.[1][2]

- Self-published on Steam and GOG.

- 8-4 published the console versions.

- In role-playing games, "LV" and "EXP" are abbreviations for "[experience] level" and "experience points", respectively, and are desirable to increase.[15]

- The endings are referred to as, respectively: the "neutral run"; the "pacifist run"; and the "no mercy run" (fan dubbed the genocide run).[13][16][17]

References

- Fox, Toby (June 13, 2017). "UNDERTALE is Coming to PlayStation!". PlayStation.Blog.

Along the way that transformed into having them develop and publish the PlayStation versions, too.

- 8-4. Undertale (Nintendo Switch). 8-4. Scene: Credits.

Nintendo Switch Conversion: 8-4, Ltd.

CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "The RPS Advent Calendar, Dec 16th: Undertale". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Davis, Ben (September 24, 2015). "Review: Undertale". Destructoid. ModernMethod. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Hudson, Laura (September 24, 2015). "In Undertale, you can choose to kill monsters — or understand them". Boing Boing. Happy Mutants. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Smith, Adam (October 15, 2015). "Conversations With Myself: On Undertale's Universal Appeal". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Cobbett, Richard (September 21, 2015). "The RPG Scrollbars: Undertale". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- Bogos, Steven (June 2, 2013). "Undertale is an EarthBound Inspired Indie RPG". The Escapist. Defy Media. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Couture, Joel (September 22, 2015). "Guilt, Friendship, and Carrot Monsters — Undertale and the Consequences of Easy Violence". IndieGames.com. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Farokhmanesh, Megan (July 7, 2013). "UnderTale combines classic RPG gameplay with a pacifist twist". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- Welhouse, Zach (October 8, 2015). "Undertale – Review". RPGamer. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Muncy, Jack (January 18, 2016). "The Best New Videogames Are All About … Videogames". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Grayson, Nathan (September 28, 2015). "Players Still Haven't Figured Out All Of Undertale's Secrets". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on February 17, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Toby Fox (September 15, 2015). Undertale (0.9.9.5 ed.). Scene: Intro.

- Moore, Michael E. (2011). Basics of Game Design. A K Peters, Ltd. p. 142. ISBN 9781568814339.

- Plagge, Kallie (January 12, 2016). "Undertale Review". IGN. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Hughes, William (December 9, 2015). "Undertale dares players to make a mistake they can never take back". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- Turi, Tim (October 15, 2015). "GI Show – Yoshi's Woolly World, Star Wars: Battlefront, Undertale's Toby Fox". Game Informer. GameStop. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Suszek, Mike (July 29, 2013). "Crowdfund Bookie, July 21–27: Terminator 2, UnderTale, Last Dream". Engadget. AOL Tech. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Feeld, Julian (October 9, 2015). "INTERVIEW: TOBY FOX OF UNDERTALE". Existential Gamer. Feeld. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Hogan, Sean (May 25, 2013). "Toby Fox's Undertale – DEV 2 DEV INTERVIEW #1". Seagaia. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Fox, Toby (June 25, 2013). "UnderTale by Toby Fox". Kickstarter. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016.

- Fox, Toby (2016). Undertale Art Book. Fangamer. ISBN 9781945908996.

- Bennett, David (October 22, 2015). "Behind the humor of Toby Fox's Undertale". Kill Screen. Kill Screen Media. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Bogos, Steven (June 25, 2013). "Undertale Dev: "Every Monster Should Feel Like an Individual"". The Escapist. Defy Media. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Isaac, Chris (December 10, 2015). "Interview: Undertale Game Creator Toby Fox". The Mary Sue. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Scarnewman, Bobby; Aldenderfer, Kris; Fox, Toby (December 15, 2015). Toph & Scar Show S1 SEASON FINALE – ft. Creator of Undertale, Toby Fox, and Storm Heroes. YouTube. Google. Event occurs at 41:54. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Couture, Joel (October 27, 2015). "Thinking for Ourselves – Toby Fox on Fighting and Introspection in Undertale". IndieGames.com. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Schreier, Jason (January 5, 2016). "Undertale Has One Of The Greatest Final Boss Fights In RPG History". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Oxford, Nadia (April 21, 2016). "Note Block Beat Box: Listening to Hopes and Dreams from Undertale". USgamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Scarnewman, Aldenderfer & Fox 2015, 1:15:10

- Tarason, Dominic (October 17, 2018). "Undertale DLC hits Taito rhythm 'em up Groove Coaster". Rock Paper Shotgun. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Leack, Jonathan (September 15, 2016). "Undertale Dev Celebrates 1 Year Anniversary With Unreleased Music". Game Revolution. Crave Online. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Yu, Jason (April 6, 2016). "An Examination of Leitmotifs and Their Use to Shape Narrative in UNDERTALE – Part 1 of 2". Gamasutra. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Yu, Jason (April 14, 2016). "An Examination of Leitmotifs and Their Use to Shape Narrative in UNDERTALE – Part 2 of 2". Gamasutra. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Hicks, Tyler (November 20, 2015). "Undertale Review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Orland, Kyle (December 28, 2015). "The best video games of 2015, as picked by the Ars editor". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Fox, Toby (July 17, 2016). "UnderTale on Twitter: "UNDERTALE is now available for Linux on Steam! Also, the game's still on sale for the next 24 hours, so..."". Twitter. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- Frank, Allegra (January 21, 2016). "Undertale's first patch claims to fix bugs, but fans found hidden content". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Matulef, Jeffrey (June 13, 2017). "Undertale is coming to PS4 and Vita this summer". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- Jenni (July 18, 2017). "Undertale Coming To The PlayStation 4 And Vita On August 15, 2017". Siliconera. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- Frank, Allegra (August 15, 2017). "Undertale's trophies are perfectly hilarious". Polygon. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- "世界的な大ヒットタイトル『UNDERTALE』がNintendo Switchで発売!". Nintendo. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- Glagowski, Peter (March 8, 2018). "Undertale will 'eventually' be on Switch". Destructoid. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- Good, Owen (March 9, 2018). "Undertale coming to Switch brings indie games' GameMaker Studio engine with it". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Soejima (August 1, 2018). "記念すべき9月15日に『UNDERTALE』発売へ!" (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Schreier, Jason (August 28, 2018). "A Ton Of New Indie Games Are Heading To Switch Soon". Kotaku. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Rowen, Nic (February 9, 2016). "Get your name in early for these Undertale figures". Destructoid. ModernMethod. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- "UNDERTALE Soundtrack". Steam. Valve. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Grayson, Nathan (January 6, 2016). "Undertale has an officially sanctioned fan album, and it's awesome". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- RichaadEB; Waters, Ace. "Determination". Bandcamp. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Gwaltney, Javy (February 6, 2016). "Official Undertale Jazz Album Live At Grillby's Released". Game Informer. GameStop. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Hamilton, Kirk (December 5, 2016). "Undertale just got a nice new musical tribute". Kotaku. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- "Undertale Soundtrack Coming to Vinyl". IGN. August 26, 2016. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- "RPGFan Music - Undertale Piano Collections". www.rpgfan.com. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- "『UNDERTALE』のピアノアレンジアルバム第2弾『UNDERTALE Piano Collections 2』が発表。Bandcampで予約開始(試聴動画アリ)". ファミ通.com. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- Glogowski, Peter (September 4, 2019). "Sans from Undertale is getting a costume in Smash Ultimate". Destructoid. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- https://m.youtube.com/watch?feature=youtu.be&v=953dc07NMEk

- Life, Nintendo (October 13, 2019). "Undertale Song Pack Arrives In Taiko no Tatsujin: Drum 'n' Fun! As Paid DLC". Nintendo Life.

- "Cult RPG Undertale gets a surprise spinoff for Halloween". The Verge. October 31, 2018. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Kent, Emma (November 2, 2018). "Undertale creator suggests it's going to be a while before we see more Deltarune". Eurogamer. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Fox, Toby. "DELTARUNE". www.deltarune.com. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Frank, Allegra (October 31, 2018). "Undertale creator's new game is Deltarune, a mysterious surprise". Polygon. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Undertale for PC Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- "Undertale". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- "Undertale". Metacritic. CBS Interactive.

- Peterson, Joel (August 15, 2017). "Review: Undertale (PS4)". Destructoid. Enthusiastic Gaming. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- Tack, Daniel (October 1, 2015). "An Enchanting, Exhilarating Journey – Undertale". Game Informer. GameStop. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Walker, Austin (September 25, 2015). "Undertale Review". Giant Bomb. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Cobbett, Robert (September 29, 2015). "Undertale review". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- Mackey, Bob (September 30, 2015). "Undertale PC Review: The Art of Surprise". USgamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- Allen, Eric Van (October 22, 2015). "Undertale Fan Makes a Sequel... In a Wrestling Game?". Paste. Paste Media Group. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- LaBella, Anthony (September 24, 2015). "You Should Play Undertale". Game Revolution. CraveOnline. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Best PC Video Games of All Time". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- Wawro, Alex (December 22, 2015). "GTA 5 leads Steam Spy's list of best-selling 2015 Steam games". Gamasutra. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- Grubb, Jeff (April 13, 2016). "Stardew Valley is one of the best-selling PC games of the year as it surpasses 1M copies sold". GamesBeat. VentureBeat. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Orland, Kyle (July 6, 2018). "Valve leaks Steam game player counts; we have the numbers". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2018. Complete list. Archived July 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Romano, Sal (February 15, 2018). "Undertale PS4 and PS Vita sales top 100,000 in Japan". Gematsu. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- Croshaw, Ben (October 28, 2015). "Undertale May Be This Year's Best Written Game". The Escapist. Defy Media. Archived from the original on October 29, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- Singal, Jesse (February 12, 2016). "Best game ever? No, but 'Undertale' warrants the hype". The Boston Globe. Boston Globe Media Partners. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- Wawro, Alex (September 14, 2016). "Undertale dev reflects on what it's like to have your game become a phenomenon". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- "Game of the Month: October – Undertale". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "The RPS Advent Calendar, Dec 16th: Undertale". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "Undertale wins GameFAQs' Best Game Ever contest". Polygon. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "The Jimquisition Game of the Year Awards 2015". The Jimquisition. December 21, 2015. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Top 5 Games of 2015". The Escapist. January 7, 2016. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "PC Game of the Year". IGN. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Destructoid's award for Best PC Game of 2015 goes to..." Destructoid. December 22, 2015. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Sarkar, Samit (March 21, 2016). "The Witcher 3 takes top honors at yet another award show, the SXSW Gaming Awards". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- "2015 Winners". National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers. March 21, 2016. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Best Story". IGN. January 12, 2016. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- "The Witcher 3, Metal Gear Solid 5 lead nominees for GDC 2016 Awards". VG247. January 8, 2016. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Her Story takes home top honors at the 18th annual IGF Awards". Gamasutra. UBM TechWeb. March 16, 2016. Archived from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- "Nominees for 2016 Independent Games Festival Awards Revealed". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Sarkar, Samit (December 20, 2016). "2016 Steam Awards finalists go all the way back to 2006". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- "The 100 best games of the decade (2010–2019): 100–51". Polygon. November 4, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Fallout 4 wins best game at BAFTAs". Gamesindustry.biz. Gamer Network. April 7, 2016. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- "Rocket League, The Witcher 3, Fallout 4, others up for BAFTA Best Game Award". VG247. March 10, 2016. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- "DICE Awards finalists include Fallout 4, Witcher 3, Life is Strange and more". Polygon. January 13, 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Vote for the Dragon Awards!". Dragon Con. August 12, 2016. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- "Global Game Awards 2015". Game Debate. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- "Here are the nominees for The Game Awards 2015". Polygon. November 13, 2015. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- "Her Story, Undertale, Darkest Dungeon receive multiple 2016 IGF Award nominations". VG247. January 6, 2016. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Bloodborne, Metal Gear Solid 5 among SXSW Gaming Award nominees". Polygon. January 25, 2016. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.