Metoac

Metoac is a name used by some to describe the Munsee-speaking Lenape and Pequot Native Americans on what is now Long Island in New York state. The term, a geographic rather than political grouping,[3] was adopted by amateur anthropologist and U.S. Congressman Silas Wood in the mistaken belief that the various bands on the island comprised distinct tribes.

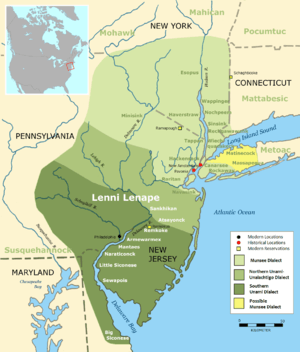

Instead, Native American peoples on Long Island are descended from two major language and cultural groups of the many Algonquian peoples who occupied Atlantic coastal areas from present-day Canada through the American South. The bands in the western part of Long Island were related to the Lenape, who had previously settled in the territory east of the Hudson River, and were related to peoples in what is now western Connecticut. Those to the east were more related culturally and linguistically to the Algonquian tribes of New England across Long Island Sound, such as the Pequot.[1][2] Wood (and earlier colonial settlers) often confused Indian place names, by which the bands were known, as the names for different tribes living there, further confusing that each was a different tribe.

Many of the place names that the Lenape and Pequot populations assigned to their villages and communities were adopted by English settlers and are still in use today. The Shinnecock Indian Nation, based in part of what is now Southampton, New York in Suffolk County, has gained federal recognition as a tribe and has a reservation there.

Etymology

"Metoac" as a collective term may have been derived by Wood from metau-hok, the Algonquian word for the rough periwinkle,[4] the shell of which small sea snail was used to make wampum, a means of exchange which played an important role in the economy of the region before and after the arrival of Europeans.[3]

Languages

The Native American population on Long Island has been estimated at 10,000 at the time of first contact.[5][6] They belonged to two major nations and spoke two languages within the Algonquian language group, reflecting their different connections to mainland peoples.[7] Native Americans in the west and in the central part of Long Island were Lenape, associated with bands of the same people in southeastern Connecticut, Eastern Pennsylvania, Lower Hudson Valley in New York, New Jersey and Delaware. These people spoke one of the R-dialects of the Lenape language. The tribes were highly decentralized and bands operated independently, establishing territory in different geographic areas.[3]

Those Native Americans who lived on the east end of the island were related to the Pequot of eastern Connecticut. They spoke a Y-dialect of the Mohegan-Montauk-Narragansett language.[2]

European colonization

European colonization of the region began in the 1620s, with Dutch colonists congregating around the lower Hudson and western Long Island. The Dutch attempted to establish jurisdiction from New Amsterdam over the western portion of Long Island (including what are now the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens).

The eastern part of Long Island was colonized by English settlers of the New England Confederation. Settlers from southern New England began to migrate to Long Island's north shore in the early eighteenth century. Indigenous populations declined significantly within a few decades of European contact, due to new infectious diseases to which they had no acquired immunity.

This separation between zones of Dutch and English influence was formalized in their Treaty of Hartford in 1650, which set a border running south from Oyster Bay. The Native Americans on Long Island played an important role in the trade economy; they fashioned shells harvested there into small beads to create sewant, or wampum (wampompeag in Lenape- a term later shortened by the English). These were used to decorate ceremonial wear and were the most highly prized.

Displacement

The Pequot War (1634–1638) in southern New England and Kieft's War (1643–1645) in the New York metropolitan area were two major conflicts between the indigenous peoples and the colonists. Exposure to new Eurasian infectious diseases, such as measles and smallpox, dramatically reduced the numbers of Native Americans on Long Island. In addition, some Native American settlements on Long Island migrated away under pressure from European encroachment. By 1659, their population was reduced to less than 500.

After the American Revolutionary War, their numbers were reduced to 162 people by 1788. By this time, Samson Occom had persuaded many survivors to join the Brothertown Indians in western upstate New York, where the Oneida people of the Iroquois Confederacy shared their reservation for several years.

Exonyms

For generations, colonists mistakenly used the place names as exonyms for peoples, thinking they referred to distinct tribes. Among the many locations on Long Island used by the native peoples, 19th-century American publications erroneously identified the following thirteen as "tribes" on Long Island:[8][9]

Metoac was a term erroneously used by amateur anthropologist and U.S. Congressman Silas Wood to describe Lenape and Pequot Native Americans on Long Island in New York state, in the belief that the various bands on the island comprised distinct tribes. He published a book in the 19th century which mistakenly claimed that several American Indian tribes were distinct to Long Island. He collectively called them the Metoac. Scholars now understand that these historic peoples were part of two major cultural groups: the Lenape and the Wappinger-Wangunk-Quinnipiac peoples, both part of the Algonquian languages family.

| Name | Alternate names | Location | Modern place names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canarsie | Carnasee | modern-day Brooklyn, New York and Maspeth, Queens, and Jamaica, New York | Canarsie, Brooklyn | According to legend, the Carnarsie sold Manhattan to the Dutch Governor Peter Minuit for "24 dollars' worth of beads and trinkets."[10] |

| Corchaug | Cochaug, Cutchogue | around Riverhead and Southold, New York on eastern Long Island | Cutchogue, New York | The Fort Corchaug Archaeological Site is on the National Register of Historic Places. |

| Manhasset | Manhansick | Shelter Island, New York | Manhasset, New York | |

| Marsapeague | Massapequa, Marsapequa, Maspeth | south shore, from the Rockaways east into Suffolk County. | Massapequa and Maspeth, Queens | |

| Matinecock | Matinecoc | Long Island North Shore from Flushing, Queens to Huntington | Matinecock, New York | |

| Mericoke | Merrick, Meroke, Merikoke, Meracock | south shore from the Rockaways into Suffolk County | Merrick, New York | |

| Montaukett | Montauk, Meanticut | East Hampton, New York | Montauk, New York | Its sagamore Wyandanch had his name on the title transfer of most of Long Island to the European settlers |

| Nissequaq | Nesaquake, Missaquogue | North Shore from Fresh Pond to Stony Brook in Suffolk County | Nissequogue, New York and the Nissequogue River | |

| Rockaway | Rechaweygh, Rechquaakie | around Rockaway and portions of Jamaica and Maspeth | The Rockaways is a place name derived from this. | |

| Secatague | Secatoag, Secatogue | Islip on the south shore. | ||

| Setauket | Setalcott | North Shore from Stony Brook to Wading River, New York | Setauket, New York | |

| Shinnecock | Southampton | Shinnecock Hills, New York and Shinnecock Inlet | The federally recognized tribe occupies the Shinnecock Reservation, New York. | |

| Unkechaug | Patchogue, Onechechaug, Patchoag, Unchachaug, Unquaches, Unquachog, Unquachock, Unchechauge | south shore from Brookhaven, New York to Southampton, New York | Patchogue, New York |

State and federal recognition

New York State has officially recognized the self-identified Shinnecock and the Unkechaug on Long Island as Native American tribes. The Shinnecock are based at Shinnecock Reservation near Southampton on the South Shore. The Unkechaug's Poospatuck Reservation at Mastic is the smallest Indian reservation in the state.

Since the mid-20th century, the Montaukett, Setalcott, and Matinnecock peoples have organized and established governments. All are seeking both state and federal recognition.

At the end of 2009, the administration of President Barack Obama announced the Shinnecock Indian Nation had met federal criteria as a tribe.[11] The Shinnecock were officially recognized by the United States government in October 2010 after a more than 30-year effort, which included suing the Department of Interior.[12] The Acting Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, George T. Skibine, issued the final determination of the tribe's recognized status on June 13, 2010.[13]

References

- Strong, John A. Algonquian Peoples of Long Island, Heart of the Lakes Publishing (March 1997). ISBN 978-1-55787-148-0

- Bragdon, Kathleen. The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Northeast,Columbia University Press (2002). ISBN 978-0-231-11452-3.

- Metoac History by Lee Sultzman

- Ricky, D.B. (1998). Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania Indians. Somerset Publishers. ISBN 9780403097722. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- longislandsoundstudy.net/about-the-sound/history/

- montaukclub.com/the-montauk-club/.../the-montauk-tribe/

- Barron, Donna. The Long Island Indians and Their New England Ancestors: Narragansett, Mohegan, Pequot & Wampanoag Tribes. AuthorHouse. June 28, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4259-3405-7

- Nathaniel Scudder, A History of Long Island From Its First Settlement By Europeans to the Year 1845, New York: 1845

- "Metoac Tribe". accessgenealogy.com. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- Islands Draw Native American, Dutch, and English Settlement, City-data.com, Retrieved December 1, 2007]

- Hakim, Danny (2009-12-15). "U.S. Eases Way to Recognition for Shinnecock". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- Hakim, Danny (June 15, 2010). "U.S. Recognizes an Indian Tribe on Long Island, Clearing the Way for a Casino". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- Darling, Nedra. "Skibine Issues a Final Determination to Acknowledge the Shinnecock Indian Nation of Long Island, NY. Archived 2010-12-05 at the Wayback Machine Office of the Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs. 15 June 2010 (retrieved 12 July 2010)