Metaphysis

The metaphysis is the narrow portion of a long bone between the epiphysis and the diaphysis.[1] It contains the growth plate, the part of the bone that grows during childhood, and as it grows it ossifies near the diaphysis and the epiphyses. The metaphysis contains a diverse population of cells including mesenchymal stem cells, which give rise to bone and fat cells, as well as hematopoietic stem cells which give tis to a variety of blood cells as well as bone-destroying cells called osteoclasts. Thus the metaphysis contains a highly metabolic set of tissues including trabecular (spongy) bone, blood vessels , as well as Marrow Adipose Tissue (MAT).

| Metaphysis | |

|---|---|

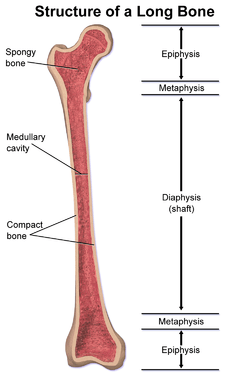

Structure of a long bone, showing the metaphysis | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /mətˈæfɪsɪs/ |

| Part of | Long bones |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | metaphysis |

| TA | A02.0.00.022 |

| FMA | 24014 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The metaphysis may be divided anatomically into three components based on tissue content: a cartilaginous component (epiphyseal plate), a bony component (metaphysis) and a fibrous component surrounding the periphery of the plate. The growth plate synchronizes chondrogenesis with osteogenesis or interstitial cartilage growth with appositional bone growth at the same that it is growing in width, bearing load and responding to local and systemic forces and factors.

During childhood, the growth plate contains the connecting cartilage enabling the bone to grow; at adulthood (between the ages of 18 to 25 years), the components of the growth plate stop growing altogether and completely ossify into solid bone.[2] In an adult, the metaphysis functions to transfer loads from weight-bearing joint surfaces to the diaphysis.[3]

Clinical significance

Because of their rich blood supply and vascular stasis, metaphyses of long bones are prone to hematogenous spread of osteomyelitis in children.[4]

Metaphyseal tumors or lesions include osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, osteoblastoma, enchondroma, fibrous dysplasia, simple bone cyst, aneurysmal bone cyst, non-ossifying fibroma, and osteoid osteoma.[5]

One of the clinical signs of rickets that doctors look for is cupping and fraying at the metaphyses when seen on X-ray.

References

- Dorland's Pocket Medical Dictionary, 27th edition

- Visual dictionary of Merriam-Webster http://visual.merriam-webster.com/human-being/anatomy/skeleton/parts-long-bone.php

- Encyclopædia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/377978/metaphysis

- Luqmani, Raashid; Robb, James; Daniel, Porter; Benjamin, Joseph (2013). Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rheumatology (second ed.). Mosby. p. 96. ISBN 9780723436805.

- "New Jersey Medical School, Pathology Department Introductory Course on Bone Tumours". Archived from the original on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

External links

- Anatomy photo: Musculoskeletal/bone/structure0/structure2 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis - "Bone, structure (Gross, Low)"