Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven

Mervyn Tuchet (sometimes Mervin Touchet), 2nd Earl of Castlehaven (1593 – 14 May 1631), was an English nobleman who was convicted of rape and sodomy and subsequently executed.

Mervyn Tuchet | |

|---|---|

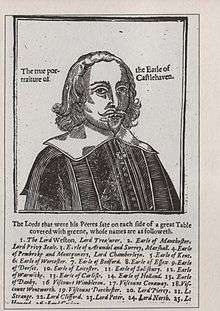

The 2nd Earl of Castlehaven, from a contemporary print published in the wake of his notorious trial. | |

| Member of Parliament Dorset | |

| In office 5 April 1614 – 7 June 1625 | |

| Justice of the Peace Dorset | |

| In office 1614–1625 | |

| Justice of the Peace Somerset | |

| In office 1614–1626 | |

| Justice of the Peace Wiltshire | |

| In office 1614–1626 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mervyn Tuchet 1593 |

| Died | 14 May 1631 Tower Hill, London |

| Cause of death | beheaded |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

A son of George Tuchet, 1st Earl of Castlehaven and 11th Baron Audley, by his wife, Lucy Mervyn, he was known by the courtesy title of Lord Audley during his father's lifetime, so is sometimes referred to as Mervyn Audley.[1]

He was knighted by James I in 1608, before he studied law at the Middle Temple. He served as Member of the Parliament of England for Dorset in the Addled Parliament of 1614 and was a Justice of the Peace for the counties of Dorset, Somerset, and Wiltshire.[1] He succeeded his father on 20 February 1616/7 as Earl of Castlehaven and Baron Audley. He left six children upon his death.[2]

Sometime before 1608[1] (records of the marriage are lacking), Lord Audley married Elizabeth Barnham, a sister-in-law of the philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon, and with her he had six children. By all accounts the marriage was a loving and successful one, ending with her death in 1622.[3] His second marriage, on 22 July 1624, at Harefield, Middlesex, was to the former Lady Anne Stanley (1580–1647), elder daughter and co-heiress of Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby (by his wife, Alice Spencer), and widow of Grey Brydges, 5th Baron Chandos. They had a daughter, Anne Touchet, who died young.[4] Lady Anne was significantly older than Castlehaven,[5] and the marriage was not a success, but in 1628 Lord Castlehaven's son was married to her thirteen-year-old daughter, Elizabeth;[5] a marriage of step-children.

Trial on charges of rape and sodomy

In 1630, Castlehaven was publicly accused of raping his wife and committing sodomy with two of his servants.[6] Castlehaven's son, James, claimed that it was the extent of Castlehaven's "uxoriousness" toward his male favourites which led to his initial lodging of a complaint.[7]

At a trial by his peers, it was stated that one such favourite, Henry Skipwith, had arrived at Fonthill Gifford in 1621 and that within a few years he was so close to Castlehaven that he sat at the family's table and was to be addressed as "Mister Skipwith" by the servants. Several years later, Giles Broadway arrived at the house and received similar treatment. It was not long before Castlehaven was providing Skipwith with an annual pension, and he was accused of attempting to have Skipwith inseminate his daughter-in-law, to produce an heir from Skipwith instead of his son. In fact, the countess and Skipwith had an adulterous relationship.

Charges were brought against Castlehaven on the complaint of his eldest son and heir, who feared disinheritance, and were heard by the Privy Council under the direction of Thomas Coventry, Lord High Steward. Lady Castlehaven gave evidence of a household which she said was infested with debauchery, and the Attorney-General acting for the prosecution explained to the court that Castlehaven had become ill because "he believed not God", an impiety which made Castlehaven unsafe. However, he insisted he was not guilty and that his wife and son had conspired together in an attempt to commit judicial murder. All witnesses against Castlehaven would gain materially by his death (as the defendant put it: "It is my estate, my Lords, that does accuse me this day, and nothing else")[5] and "News writers throughout England and as far away as Massachusetts Bay speculated about the outcome."[5]

Castlehaven maintained his innocence, and the trial aroused considerable public debate, After some deliberation the Privy Council returned a unanimous verdict of guilty on the charge of rape. The sodomy charge was also upheld, but by a slim margin as not all jurors agreed that actual penetration had taken place.[6] The case remains of interest to some as an early trial concerning male homosexuality, but ultimately its greatest influence proved to be as a precedent in spousal rights, as it became the leading case establishing an injured wife's right to testify against her husband.[5]

Castlehaven was convicted, attainted, and three weeks later beheaded on Tower Hill for his sexual crimes: namely the "unnatural crime" of sodomy, committed with his page Laurence (or Florence) FitzPatrick, who confessed to the crime and was executed; and assisting Giles Browning (alias Broadway), who was also executed, in the rape of his wife Anne, Countess of Castlehaven, in which Lord Castlehaven was found to have participated by restraining her.

The page who was executed, Laurence FitzPatrick, testified that Lady Castlehaven "was the wickedest woman in the world, and had more to answer for than any woman that lived". In The Complete Peerage, Cokayne adds that the death of Castlehaven was certainly brought about by his wife's manipulations and that her undoubted adultery with one Ampthill and with Henry Skipwith renders her motives suspicious. According to the historian Cynthia B. Herrup,[8] Anne was the equal of Lord Castlehaven in immorality.

Under the terms of the attainder, Castlehaven forfeited his English barony of Audley, created for heirs general, but retained his Irish earldom and barony since it was an entailed honour protected by the statute De Donis. When he was beheaded on Tower Hill on 14 May 1631, those Irish titles passed to his son James.

Children

Mervyn Touchet's first marriage (before 1608) was with Elizabeth Barnham (1592 – c. 1622/4), daughter of London alderman Benedict Barnham and his wife, Dorothea Smith, and they had six surviving children:

- James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven (1612–1684), who married Elizabeth Brydges (1614/5–1679), daughter of his stepmother, but left no surviving children

- Lady Frances Touchet (born 1617)

- Hon. George Touchet (died c. 1689), who became a Benedictine monk

- Mervyn Tuchet, 4th Earl of Castlehaven (died 1686)

- Lady Lucy Touchet (died 1662)

- Lady Dorothy Touchet (died 1635)

His second marriage was with Lady Anne Stanley, 22 July 1624, daughter of Ferdinando Stanley and Alice Spencer. From this marriage there was one daughter:

- Anne Touchet, died young.

References

- Ferris, John P.; Hunneyball, Paul (2010). "Audley, alias Tuchet, Sir Mervyn (c.1588-1631), of Stalbridge, Dorset; later of Fonthill Gifford, Wilts". The History of Parliament.

- Herrup 1999, p. ix.

- Herrup 1999, p. 12.

- Herrup, Cynthia B. (January 2008) [2004]. "Touchet, Mervin, second earl of Castlehaven (1593–1631)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/66794. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Massarella, Derek (November 2017). ""& thus ended the buisinisse": A Buggery Trial on the East India Company Ship Mary in 1636". The Mariner's Mirror. Portsmouth, United Kingdom: Society for Nautical Research. 103 (4): 423.

- Herrup 1999, p. 19.

- Herrup, Cynthia B. (1999). A House in Gross Disorder: sex, law, and the 2nd Earl of Castlehaven. Oxford University Press.

- Herrup, Cynthia (1999). A House in Gross Disorder: Sex, Law, and the 2nd Earl of Castlehaven. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512518-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lacey, Brian (2008). Terrible Queer Creatures: A History of Homosexuality in Ireland. Wordwell Books.

- Leigh Rayment's Peerage Pages

- Rictor Norton, "The Trial of Mervyn Touchet, Earl of Castlehaven, 1631", The Great Queens of History. Updated 8 August 2009

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Tuchet |

Earl of Castlehaven 1617–1631 |

Succeeded by James Tuchet |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Preceded by George Tuchet |

Baron Audley 1617–1631 |

Forfeit Title next held by James Tuchet |