Mellotron

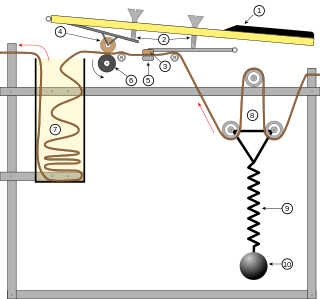

The Mellotron is an electro-mechanical musical instrument developed in Birmingham, England, in 1963. It evolved from the similar Chamberlin, but could be mass-produced more efficiently. The instrument is played by pressing its keys, each of which pushes a length of magnetic tape against a capstan, which pulls it across a playback head. Then as the key is released, the tape is retracted by a spring to its initial position. Different portions of the tape can be played to access different sounds.

| Mellotron | |

|---|---|

A Mellotron Mk VI | |

| Manufacturer | Bradmatic/Mellotronics (1963–70) Streetly Electronics (1970–86, 2007–present) |

| Dates | 1963 (Mk I) 1964 (Mk II) 1968 (M300) 1970 (M400) 2007 (M4000) |

| Technical specifications | |

| Polyphony | Full |

| Oscillator | Audio tape |

| Synthesis type | Sample-based synthesis |

| Input/output | |

| Keyboard | 1 or 2 x 35 note manuals (G2–F5) |

The first models were designed to be used in the home and contained a variety of sounds, including automatic accompaniments. Bandleader Eric Robinson and television personality David Nixon were heavily involved in introductory promotion of the instruments. A number of other celebrities such as Princess Margaret were early adopters. The instrument began to be used by rock and pop groups in the mid to late 1960s. The Moody Blues's keyboardist Mike Pinder used it extensively on the band's 1967 orchestral collaboration Days of Future Passed. The Beatles used the instrument on several tracks, including the hit single "Strawberry Fields Forever". The Mellotron was subsequently used by groups like King Crimson and Genesis, becoming a common instrument in progressive rock. Later models, such as the best selling M400, dispensed with the accompaniments and some sound selection controls so it could be used by touring musicians. The instrument's popularity declined in the 1980s after the introduction of polyphonic synthesizers and samplers, despite a number of high-profile users like Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and XTC.

Production of the Mellotron ceased in 1986, but it regained popularity in the 1990s and was used by several notable bands, such as Oasis and Radiohead. This led to the resurrection of the original manufacturer, Streetly Electronics. In 2007, Streetly produced the M4000, which combined the layout of the M400 with the bank selection of earlier models.

Operation

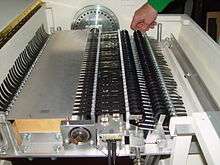

The Mellotron uses the same concept as a sampler, but generates its sound using analogue samples recorded on audio tape rather than digital samples. When a key is pressed, a tape connected to it is pushed against a playback head, as in a tape deck. While the key remains depressed, the tape is drawn over the head, and a sound is played. When the key is released, a spring pulls the tape back to its original position.[1] A variety of sounds are available on the instrument. On earlier models, the instrument is split into "lead" and "rhythm" sections. There is a choice of six "stations" of rhythm sounds, each containing three rhythm tracks and three fill tracks. The fill tracks can also be mixed together.[2]:17–18 Similarly, there is a choice of six lead stations, each containing three lead instruments which can be mixed. In the centre of the Mellotron, there is a tuning button that allows a variation in both pitch and tempo.[2]:19 Later models do not have the concept of stations and have a single knob to select a sound, along with the tuning control. However, the frame containing the tapes is designed to be removed, and replaced with one with different sounds.[3]

Although the Mellotron was designed to reproduce the sound of the original instrument, replaying a tape creates minor fluctuations in pitch (wow and flutter) and amplitude, so a note sounds slightly different each time it is played.[4] Pressing a key harder allows the head to come into contact under greater pressure, to the extent that the Mellotron responds to aftertouch.[5]

Another factor in the Mellotron's sound is that the individual notes were recorded in isolation. For a musician accustomed to playing in an orchestral setting, this was unusual, and meant that they had nothing against which to intonate. Noted cellist Reginald Kirby refused to downtune his cello to cover the lower range of the Mellotron, and so the bottom notes are actually performed on a double bass. According to Mellotron author Nick Awde, one note of the string sounds contains the sound of a chair being scraped in the background.[1]

The original Mellotrons were intended to be used in the home or in clubs and were not designed for touring bands. Even the later M400, which was designed to be as portable as possible, weighed over 122 pounds (55 kg).[6] Smoke, variations in temperature, and humidity were also detrimental to the instrument's reliability. Moving the instrument between cold storage rooms and brightly lit stages could cause the tapes to stretch and stick on the capstan. Leslie Bradley recalls receiving some Mellotrons in for a repair "looking like a blacksmith had shaped horseshoes on top".[7] Pressing too many keys at once caused the motor to drag, resulting in the notes sounding flat.[8] Robert Fripp stated that "[t]uning a Mellotron doesn't".[9][10] Dave Kean, an expert Mellotron repairer, recommends that older Mellotrons should not be immediately used after a period of inactivity, as the tape heads can become magnetised in storage and destroy the recordings on them if played.[7]

History

Although tape samplers had been explored in research studios, the first commercially available keyboard-driven tape instruments were built and sold by California-based Harry Chamberlin.[11] The concept of the Mellotron originated when Chamberlin's sales agent, Bill Fransen, brought two of Chamberlin's Musicmaster 600 instruments to England in 1962 to search for someone who could manufacture 70 matching tape heads for future Chamberlins. He met Frank, Norman and Les Bradley of tape engineering company Bradmatic Ltd, who said they could improve on the original design.[12] The Bradleys subsequently met bandleader Eric Robinson, who agreed to help finance the recording of the necessary instruments and sounds. Together with the Bradleys and television celebrity David Nixon, they formed a company, Mellotronics, in order to market the instrument.[13] Robinson was particularly enthusiastic about the Mellotron, because he felt it would revitalise his career, which was then on the wane. He arranged the recording sessions at IBC Studios in London, which he co-owned with George Clouston.[14]

The first model to be commercially manufactured was the Mk I in 1963. An updated version, the Mk II, was released the following year which featured the full set of sounds selectable by banks and stations.[12] The instrument was expensive, costing £1,000, at a time when a typical house cost £2,000–£3,000.[15]

Fransen failed to explain to the Bradleys that he was not the owner of the concept, and Chamberlin was unhappy with the fact that someone overseas was copying his idea. After some acrimony between the two parties, a deal was struck between them in 1966, whereby they would both continue to manufacture instruments independently.[16] Bradmatic renamed themselves Streetly Electronics in 1970.[17]

.jpg)

In 1970, the model M400 was released, which contained 35 notes (G–F) and a removable tape frame. It sold over 1,800 units.[7] By the early 1970s, hundreds of the instruments were assembled and sold by EMI under exclusive licence.[8] Following a financial and trademark dispute through a US distribution agreement, the Mellotron name was acquired by American-based Sound Sales.[18] Streetly-manufactured instruments after 1976 were sold under the name Novatron.[17] The American Mellotron distributor, Sound Sales, produced their own Mellotron model, the 4-Track, in the early 1980s. At the same time Streetly Electronics produced a road-cased version of the 400 – the T550 Novatron.[19] By the mid-1980s, both Sound Sales and Streetly Electronics suffered severe financial setbacks, losing their market to synthesizers and solid-state electronic samplers, which rendered the Mellotron essentially obsolete. The company folded in 1986, and Les Bradley threw most of the manufacturing equipment into a skip.[20] From 1963 until Streetly's closure, around 2,500 units had been built.[21]

Streetly Electronics was subsequently reactivated by Les Bradley's son John and Martin Smith.[22] After Les Bradley's death in 1997, they decided to resume full-time operation as a support and refurbishment business. By 2007, the stock of available instruments to repair and restore was diminishing, so they decided to build a new model, which became the M4000. The instrument combined the features of several previous models, and featured the layout and chassis of an M400 but with a digital bank selector that emulated the mechanical original in the Mk II.[3][23]

Notable users

The first notable musician to use the Mellotron was variety pianist Geoff Unwin, who was specifically hired by Robinson in 1962 to promote the use of the instrument. He toured with a Mk II Mellotron and made numerous appearances on television and radio.[24] Unwin claimed that the automatic backing tracks on the Mk II's left-hand keyboard allowed him to provide more accomplished performances than his own basic skills on the piano could provide.[25]

The earlier 1960s Mk II units were made for the home and the characteristics of the instrument attracted a number of celebrities. Among the early Mellotron owners were Princess Margaret,[26] Peter Sellers,[27] King Hussein of Jordan[15] and Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard[28] (whose Mellotron is now installed in the Church of Scientology's head UK office at Saint Hill Manor).[29] According to Robin Douglas-Home, Princess Margaret "adored it; (Lord Snowdon) positively loathed it".[27]

After Mellotronics had targeted them as a potential customer, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop became interested in the possibilities of the instrument, hoping it would allow them to increase throughput. The corporation used two custom-made models that employed recorded sound effects throughout 1963 and 1964, but had problems with fluctuating tape speed and found the sound wasn't up to professional broadcast quality.[30] The Mellotron was eventually dropped in favour of electronic oscillators and synthesizers.[31]

British multi-instrumentalist Graham Bond is considered the first rock musician to record with a Mellotron, beginning in 1965. The first hit song to feature a Mellotron Mk II was "Baby Can It Be True", which Bond performed live with the machine in televised performances, using solenoids to trigger the tapes from his Hammond organ.[32] This was followed by Manfred Mann, who used its reed sound on their late 1966 single "Semi-Detached Suburban Mr James". The band then included multiple Mellotron parts on their follow-up single, "Ha! Ha! Said the Clown".[33]

There's one thing I can do /

Play my Mellotron for you /

Try to blow away your city blues

Mike Pinder worked at Streetly Electronics for 18 months in the early 1960s as a tester, and was immediately excited by the possibilities of the instrument.[35] After trying piano and Hammond organ, he settled on the Mellotron as the instrument of choice for his band, the Moody Blues, purchasing a second-hand model from Fort Dunlop Working Men's Club in Birmingham[36] and using it extensively on every album from Days of Future Passed (1967) to Octave (1978).[37] Pinder says he introduced John Lennon and Paul McCartney to the Mellotron, and convinced each of them to buy one.[37] The Beatles hired a machine and used it on their single "Strawberry Fields Forever", recorded in various takes between November and December 1966.[38][39] Author Mark Cunningham describes the part in "Strawberry Fields Forever" as "probably the most famous Mellotron figure of all-time".[40] Though producer George Martin was unconvinced by the instrument, describing it "as if a Neanderthal piano had impregnated a primitive electronic keyboard",[16] they continued to compose and record with various Mellotrons for the albums Magical Mystery Tour (1967)[41] and The Beatles (1968, also known as "the White Album").[42] McCartney went on to use the Mellotron sporadically in his solo career.[43]

The instrument became increasingly popular among rock and pop bands during the psychedelic era, adding what author Thom Holmes terms "an eerie, unearthly sound" to their recordings.[44] Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones played a Mellotron on several of his band's songs over 1967–68. These include "We Love You", where he used the instrument to create a Moroccan-sounding horn section,[45] "She's a Rainbow",[46] "2000 Light Years from Home"[21] and "Jigsaw Puzzle".[47]

The Mellotron became a key instrument in progressive rock. King Crimson bought two Mellotrons when forming in 1969.[48] They were aware of Pinder's contributions to the Moody Blues and did not want to sound similar, but concluded there was no other way of generating the orchestral sound.[49] The instrument was originally played by Ian McDonald,[50] and subsequently by Robert Fripp on McDonald's departure. Later member David Cross recalled he did not particularly want to play the Mellotron, but felt that it was simply what he needed to do as a member of the band.[51] Tony Banks bought a Mellotron from Fripp in 1971, which he claimed was previously used by King Crimson, to use with Genesis. He decided to approach the instrument in a different way to a typical orchestra, using block chords, and later stated that he used it in the same manner as a synth pad on later albums.[52] His unaccompanied introduction to "Watcher of the Skies" on the album Foxtrot (1972), played on a Mk II with combined strings and brass, became significant enough that Streetly Electronics provided a "Watcher Mix" sound with the M4000.[3] Banks claims to still have a Mellotron in storage, but does not feel inclined to use it as he generally prefers to use up-to-date technology.[53] Barclay James Harvest's Woolly Wolstenholme bought an M300 primarily to use for string sounds,[54] and continued to play the instrument live into the 2000s as part of a reformed band.[55] Jethro Tull used a Mellotron on their last standalone single, "The Witch's Promise", to emulate a string section.

Rick Wakeman played Mellotron on David Bowie's 1969 hit song "Space Oddity". Having previously found it difficult to keep in tune, Wakeman had discovered a way to do so using a special fingering technique.[56]

Various Elton John songs featured the Mellotron, including hit singles "Daniel"[57][58] and "Island Girl" (with James Newton Howard performing on the latter).[59][60]

The Mellotron was used by German electronic band Tangerine Dream through the 1970s,[61] on albums such as Atem (1973),[61] Phaedra (1974),[62] Rubycon (1975),[63] Stratosfear (1976),[64] and Encore (1977).[64] In 1983, the band's Christopher Franke asked Mellotronics if they could produce a digital model, as the group migrated towards using samplers.[65]

Though the Mellotron was not extensively used in the 1980s, a number of bands featured it as a prominent instrument. One of the few UK post-punk bands to do so was Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, who featured it heavily on their platinum-selling 1981 album Architecture & Morality. Andy McCluskey has stated they used the Mellotron because they were starting to run into limitations of the cheap monophonic synthesizers they had used up to that point. He bought a second-hand M400 and was immediately impressed with the strings and choir sounds.[66] XTC's Dave Gregory recalls seeing bands using Mellotrons when growing up in the 1970s, and thought it would be an interesting addition to the group's sound. He bought a second-hand model in 1982 for £165, and first used it on the album Mummer (1983).[67] IQ's Martin Orford bought a second-hand M400 and used it primarily for visual appeal rather than musical quality or convenience.[68]

The Mellotron resurfaced in 1995 on Oasis' album (What's the Story) Morning Glory?[69] The instrument was played by both Noel Gallagher and Paul Arthurs on several tracks, but a particularly prominent use was the cello sound on the hit single "Wonderwall", played by Arthurs.[70] Radiohead asked Streetly Electronics to restore and repair a model for them in 1997,[71] and recorded with it on several tracks for their album OK Computer (1997).[72] The French electronic duo AIR extensively used a M400 on their two first albums Moon Safari in 1998 and The Virgin Suicides in 1999.[73]

Spock's Beard's Ryo Okumoto is a fan of the Mellotron, saying it characterises the sound of the band.[74] Porcupine Tree's Steven Wilson has acquired one of King Crimson's old Mellotrons[75] and, in 2013, gave a demonstration of the instrument in celebration of its 50th anniversary.[76]

Competitors

Alternative versions of the Mellotron were manufactured by competitors in the early to mid-1970s. The Mattel Optigan was a toy keyboard designed to be used in the home, which played back sounds using optical discs.[77] This was followed by the Vako Orchestron in 1975, which used a more professional-sounding version of the same technology. It was popularised by Patrick Moraz.[78]

List of models

- Mk I (1963) – double manual (35 notes on each). Very similar to the Chamberlin Music Master 600. About 10 were made.[19]

- Mk II (1964) – double manual. 18 sounds on each manual. Organ-style cabinet, two 12-inch internal speakers and amp. Weight 160 kg.[12] About 160 were made.[19]

- FX console (1965) – double manual with sound effects. Designed to be quieter than the Mk II, with a different DC motor and a solid-state power amplifier.[8]

- M300 (1968) – 52-note single manual, some with pitch wheel-control, and some without. About 60 were made.[19]

- M400 (1970) – 35-note single manual. The most common and portable model. About 1,800 units were made. It has three different sounds per frame.[12]

- EMI M400 (1970) – a special version of the M400 manufactured by EMI music company in Britain under licence from Mellotronics. 100 of this model were made.[8]

- Mark V (1975) – double-manual Mellotron, with the internals of two M400s plus additional tone and control features.[8] Around nine were made.[19]

- Novatron Mark V (1977) – the same as the Mellotron Mark V, but under a different name.[19]

- Novatron 400 (1978) – as above; a Mellotron M400 with a different name-plate.[19]

- T550 (1981) – a flight-cased version of Novatron 400.[8]

- 4 Track (1980) – very rare model; only about five were ever made.[19]

- Mark VI (1999) – an improved version of the M400. The first Mellotron to be produced since Streetly Electronics went out of business in 1986.[8]

- Mark VII – basically an upgraded Mark V. Like the Mark VI, produced in the new factory in Stockholm.[79]

- Skellotron (2005) – an M400 in a transparent glass case. Only one was made.[3]

- M4000 (2007) – one manual, 24 sounds. An improved version of the Mk II with cycling mechanism. Made by Streetly Electronics.[3]

Related products

- M4000D (2010) – a single-manual digital product that does not feature tapes. Made at the Mellotron factory in Stockholm.[79]

- Electro-Harmonix MEL9 Tape Replay Machine (2016) – simulator pedal

See also

- List of Mellotron recordings

- String synthesizer, another instrument used to imitate orchestral ensembles

References

- Awde 2008, p. 17.

- Mellotron Mk II Service Manual (PDF). Streetly Electronics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Reid, Gordon (October 2007). "Streetly Mellotron M4000". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Awde 2008, p. 16.

- Vail 2000, p. 230.

- Awde 2008, p. 23.

- Vail 2000, p. 233.

- Reid, Gordon (August 2002). "Rebirth of the Cool : The Mellotron Mk VI". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- The Night Watch (Media notes). King Crimson. Discipline Global Mobile. 1997.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Albiez, Sean; Pattie, David (2011). Kraftwerk: Music Non-Stop. Continuum. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4411-9136-6.

- "The Chamberlin history". Clavia. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "History of the Mellotron". Clavia. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- Awde 2008, pp. 44–46.

- Awde 2008, pp. 64–66.

- Shennan, Paddy (31 October 2008). "I gave Lennon a few rock tips". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- Brice 2001, p. 107.

- Awde 2008, p. 44.

- "Sound Sales brings Mellotron to the United States". Music Trades. Music Trades Corporation. 126 (1–6): 69. 1978.

- Vail 2000, p. 232.

- Awde 2008, p. 57.

- Holmes 2012, p. 448.

- Awde 2008, p. 33.

- Awde 2008, p. 45.

- Awde 2008, p. 59.

- Awde 2008, p. 69.

- Aronson, Theo (1997). Princess Margaret: A Biography. Regnery Pub. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-89526-409-1.

- Lewis, Roger (1995). The life and death of Peter Sellers. Arrow. p. 939. ISBN 978-0-09-974700-0.

- Thompson, Andy. "Oddball Owners". Planet Mellotron. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "Clients". Streetly Electronics. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- Niebur 2010, p. 126.

- Niebur 2010, p. 127.

- Awde 2008, p. 91.

- Cunningham 1998, pp. 126–27.

- Pinder, Michael (1978). "One Step Into The Light Lyrics". Octave. Retrieved 16 October 2014. cited at Metrolyrics

- Awde 2008, pp. 88–89.

- Awde 2008, p. 169.

- Awde 2008, p. 94.

- Everett 1999, p. 146.

- Pinder, Mike. "Mellotron". Mike Pinder (Official Web Site). Archived from the original on 20 June 2007.

- Cunningham 1998, p. 127.

- Everett 1999, p. 247.

- Everett 1999, p. 248.

- Benitez, Vincent P. (2010). The Words and Music of Paul McCartney: The Solo Years. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. pp. 23, 47, 86, 139. ISBN 978-0-313-34969-0.

- Holmes 2012, pp. 448–49.

- Davis, Stephen (2001). Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. New York, NY: Broadway Books. pp. 209–10. ISBN 0-7679-0312-9.

- Thompson, Gordon (2008). Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out. Oxford University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-195-33318-3.

- Clayson, Alan (2008). The Rolling Stones: Beggars Banquet – Legendary sessions. Billboard Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-823-08397-8.

- "Crimson's trons". Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Awde 2008, pp. 116–117.

- Awde 2008, p. 118.

- Awde 2008, p. 187.

- Awde 2008, pp. 200–201.

- Jenkins 2012, p. 246.

- Awde 2008, p. 133.

- Awde 2008, p. 148.

- Rick Wakeman (8 January 2017). "The day I played the Mellotron for David Bowie". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Elton John - Don't Shoot Me I'm Only The Piano Player". Discogs. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Dont Shoot Me..." Albumlinernotes.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Elton John - Rock Of The Westies". Discogs. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "To Be Continued Disc 3". Albumlinernotes.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Stump 1997, p. 39.

- Mera, Miguel; Burnand, David (2006). European Film Music. Ashgate Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7546-3659-5.

- Stump 1997, p. 64.

- Stump 1997, p. 70.

- Stump 1997, p. 119.

- Awde 2008, p. 401.

- Awde 2008, p. 387.

- Awde 2008, p. 455.

- The Mojo Collection: 4th Edition. Canongate Books. 2007. p. 622. ISBN 978-1-84767-643-6.

- Buskin, Richard (November 2012). "Oasis "Wonderwall" : Classic Tracks". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Etheridge, David (October 2007). "Mellotron M4000". Performing Musician. Retrieved 3 September 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Letts, Marianne Tatom (2010). Radiohead and the Resistant Concept Album: How to Disappear Completely. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-253-00491-8.

- Thompson, Andy. "AIR". Planet Mellotron. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jenkins 2012, p. 251.

- Orant, Tony (20 September 2013). "Adam Holzman straddles Prog Rock and Jazz Fusion". Keyboard Magazine. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Blackmarquis, Philippe (30 October 2013). "Steven Wilson – review of the concert at the Depot in Leuven". Peek a Boo Magazine. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Vail 2000, pp. 97–98.

- Vail 2000, p. 97.

- "Mellotron Mark VI, Mark VII, M4000D". Mellotron (official site). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Books

- Awde, Nick (2008). Mellotron: The Machines and the Musicians that Revolutionised Rock. Bennett & Bloom. ISBN 978-1-898948-02-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brice, Richard (2001). Music Engineering. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-7506-5040-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cunningham, Mark (1998). Good Vibrations: A History of Record Production. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 978-1860742422.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802960-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Thom (2012). Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture (4th edn). New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-89636-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkins, Mark (2012). Analog Synthesizers: Understanding, Performing, Buying – From the Legacy of Moog to Software Synthesis. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-136-12277-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Niebur, Louis (2010). Special Sound: The Creation and Legacy of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536840-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stump, Paul (1997). Digital Gothic: A Critical Discography of Tangerine Dream. SAF Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-946719-18-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vail, Mark (2000). Keyboard Magazine Presents Vintage Synthesizers: Pioneering Designers, Groundbreaking Instruments, Collecting Tips, Mutants of Technology. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-603-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Radcliffe, Mark (3 June 2006). "Sampledelica! The History of the Mellotron". BBC Radio 4. BBC. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "The Mellotron". Music Technology. Vol. 3 no. 5. April 1989. p. 24. ISSN 0957-6606. OCLC 24835173.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mellotrons. |

- Mellotron.com – US manufacturers and trademark owners

- Mellotronics.com – Streetly Electronics, UK manufacturers

- Planet Mellotron – List of Mellotron recordings and album reviews

- Mellotron Info – History and inner workings by self-confessed Mellyholic Norm Leete

- The Mellotron on '120 years Of Electronic Music'