Meetup

Meetup is a service used to organize online groups that host in-person events for people with similar interests. It was founded in 2002 by Chairman Scott Heiferman and four co-founders. The company was acquired by WeWork in 2017 and remains headquartered in New York City.[3] WeWork sold it to AlleyCorp, an early stage NY-focused venture fund and incubator, in March 2020.[4]

| |

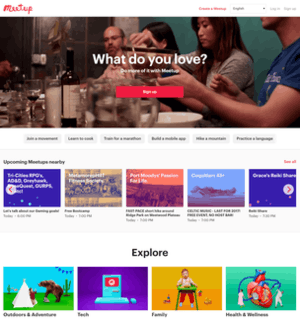

Screenshot  | |

Type of site | Membership software |

|---|---|

| Available in | English-default, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Korean, Dutch, Thai, Russian and Turkish |

| Owner | AlleyCorp, an early stage venture fund and incubator |

| URL | meetup |

| Alexa rank | |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Required to join a group |

| Launched | June 12, 2002[2] |

History

Early history

Meetup was founded in June 2002[5][6] by Scott Heiferman and five co-founders.[7][8] The idea for Meetup came from Heiferman meeting his neighbors in New York City for the first time after the September 11 attacks on the Twin Towers.[9][10] Heiferman was also influenced by the book Bowling Alone,[11] which is about the deterioration of community in American culture.[12] Some initial funding for the venture was raised from friends and family, which was followed by a funding round with angel investors.[13]

The early version of Meetup generated revenues by charging a fee to venues in exchange for bringing Meetup users to their business.[14] Once enough users added themselves to a group, Meetup would send the group members an email, asking them to vote on one of three sponsoring venues for the group to meet at.[14][15] Within a few months of Meetup launching, 56,000 users had joined the site.[6][11]

Meetup was originally intended to focus on hobbies and interests,[5] but it was popularized by Presidential hopeful Howard Dean.[16] Meetup developed paid services to help the Dean campaign to meet with Meetup users.[11] Dean also publicized Meetup groups of supporters in his speeches and on his website.[17] At the peak of Dean's campaign, 143,000 users had joined Meetup groups for Dean supporters.[5] Afterwards, Meetup became a routine part of internet campaigning for American politicians.[11][18]

Recent history

Meetup started charging a fee to group organizers in early 2005.[19] Initially, changes to the website had to be approved by two committees.[20] In 2009, Meetup started running hackathons, where employees came up with new features that would be implemented if their coworkers supported it.[20] The website was redesigned in 2013.[21] Meetup had 8 million users in 2010,[22] and 25.5 million users by 2013.[23]

In 2013, Meetup acquired a struggling email collaboration company called Dispatch.[24][25] In 2014, a hacker shut down Meetup with a DDoS attack, the hacker claimed to be funded by a competitor.[26] In 2017, Meetup created 1,000 #resist Meetup groups in response to the Trump travel ban.[27] This caused some Trump supporters to leave the site[27] or call for a boycott.[28] Meetup also partnered with a labor group to organize anti-Trump protests.[27]

Meetup was acquired by WeWork in late 2017 for about $156 million.[29] WeWork spaces are predominantly used during work hours, while Meetup events take place mostly on evenings and weekends.[30] Some former employees said there was a 10% layoff after the acquisition.[31]

In 2018, Scott Heiferman stepped down as CEO and former Investopedia CEO David Siegel took his place. Heiferman became Chairman of the company.[32][33]

In October 2019, Meetup began to test a different pricing model in two US states,[34] reducing the costs that must be paid by organizers of $23.99/month or $98.94/six months, but requiring users to pay a $2 fee in order to RSVP for events leaving several users angry.[35]

In March 2020, WeWork sold Meetup to AlleyCorp and other investors, reportedly at a substantial loss[36]. The deal added AlleyCorp's Kevin P. Ryan onto Meetup's board.[4]

Services

Meetup is an online service used to create groups that host local in-person events.[37][38] As of 2017, there are about 35 million Meetup users.[39] Each user can be a member of multiple groups or RSVP for any number of events.[40] Users are usually using the website to find friends, share a hobby, or for professional networking.[40] Meetup users do not have "followers" or other direct connections with each other like on other social media sites.[40]

Meetup users self-organize into groups.[40] As of 2017, there are about 225,000 Meetup groups in 180 countries.[38] Each group has a different topic, size, and rules.[16][38] Groups are associated with one of 30+ categories and any number of more than 18,000 tags that identify the group's theme.[40] The most popular categories are "adventure and outdoor activities, career and business, and parents and family."[16] Most events are on a structured schedule each week or month at a local venue,[38] typically on evenings or weekends.[40]

Meetup groups are run by approximately 140,000 organizers.[38] Any Meetup user can be an organizer.[16] Organizers set up groups, organize events, and develop event content.[16] They also pay a fee to run the group, under the expectation of sharing the cost with members that attend events.[38] Meetup has policies against organizing meetups around a commercial interest, hate speech, or groups that do not meet in-person.[38] This policy, against organizing meetups around commercial interests is not only not enforced; but, the Meetup company intentionally and deliberately ignore the policy and allow such to become Meetup groups. About 28% of organizers have sponsors that provide venues, drinks, and event content.[16][38]

References

- "meetup.com Competitive Analysis, Marketing Mix and Traffic - Alexa". meetup.com. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- Jeffries, Adrianne (January 21, 2011). "The Long and Curious History of Meetup.com". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- "Meetup company profile - Office locations, Competitors, Financials, Employees, Key People, News | Craft.co". craft.co. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Perez, Sarah (March 30, 2020). "WeWork sells off social network Meetup to AlleyCorp and other investors". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- Sifry, Micah; CNN, Special to (November 7, 2011). "From Howard Dean to the tea party: The power of Meetup.com". CNN. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Cox, Jonathan (October 10, 2002). "Interest Grows in Raleigh, N.C., around Offline Social Gatherings". Knight Ridder Tribune Business News.

- Review, MIT Technology. "Innovator Under 35: Scott Heiferman, 32". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Evans, Teri (June 7, 2011). "Meetup's Scott Heiferman on Connecting Communities". Entrepreneur. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Benz, Kate (January 23, 2014). "Pittsburgh Meetup members use the Internet to get off the Internet". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Ramanathan, Lavanya (October 13, 2011). "One week of Meetups". Washington Post. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Overfelt, Maggie (October 2003). "Taking America Offline". Fortune Small Business.

- Gordinier, J. (2008). X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft But Can Still Keep Everything from Sucking. Viking. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-670-01858-1. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Jeffries, Adrianne (January 21, 2011). "The Long and Curious History of Meetup.com". Observer. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Oliviero, Helena (November 25, 2002). "Web Site Links up Like Minds". The Atlanta Journal. p. E.1.

- Gilbert, Sarah (December 8, 2002). "I'm on the List: Virtual Communities: Not Just for Loners Anymore". The New York Post.

- Toledano, Margalit; Maplesden, Alexander (May 24, 2016). "Facilitating community networks: Public relations skills and non-professional organizers". Public Relations Review. 42 (4): 713–722. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.04.005.

- Gray, Chris (February 11, 2004). "MeetUp.com Working to Become a Force in Local, State Politics". Knight Ridder Tribune. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018.

- "Candidates Hope Voters Meetup.com". Indianapolis Star. September 2003. p. B.1.

- Troise, Damian J. (February 6, 2015). "Meetup Starts Charging Fee in Effort to Keep Users Involved". Inc.com. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Taylor, Chris (May 6, 2009). "Meetup: An office where group anarchy works". CNNMoney. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Ong, Josh (September 12, 2013). "Meetup Simplifies Its Member Homepage As It Pursues A Unified Design". The Next Web. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Haupt, Angela (December 13, 2010). "Meetup.com Helps Connect Like-minded People". US News & World Report. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Lai, Chih-Hui; Katz, James E. (May 31, 2016). "Volunteer associations in the Internet age: Ecological approach to understanding collective action". The Information Society. 32 (4): 241–255. doi:10.1080/01972243.2016.1177761. ISSN 0197-2243.

- Farr, Christina (October 9, 2013). "How meta! Meetup just acquired Dispatch, which got its start at a meetup". VentureBeat. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Perez, Sarah (October 9, 2013). "Meetup Makes Its First Acquisition With Dispatch, Will Roll Out Improved Messaging & Communications In Early 2014". TechCrunch. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Colón, Marcos (March 3, 2014). "Meetup battles prolonged DDoS attack". SC Media US. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "Meetup.com takes risky leap into the Trump resistance". Associated Press. March 19, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Perez, Sarah (February 16, 2017). "Trump Supporters Boycott Meetup After Company Creates #Resist Groups, Makes its Politics Known". Techcrunch. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Hempel, Jessi (November 28, 2017). "WeWork is Buying Meetup Amid an Increasingly Disconnected World". WIRED. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Hufford, Austen (November 28, 2017). "WeWork to Buy Meetup, Targeting Off-Hours Gatherings". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Conger, Kate (February 16, 2018). "The Mess at Meetup". Gizmodo. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Meetup CEO Scott Heiferman moves into chairman role". TechCrunch. July 17, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- "WeWork-owned Meetup brings on David Siegel as CEO". TechCrunch. October 30, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Siegel, David. "Payment test update". www.meetup.com. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Deahl, Dani (2019-10-15). "Meetup wants to charge users $2 just to RSVP for events — and some are furious". The Verge. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- https://techcrunch.com/2020/03/30/wework-sells-off-social-network-meetup-to-alleycorp-and-other-investors/

- Weinberg, Bruce; Williams, Christine (July–September 2006). "The 2004 US Presidential campaign: Impact of hybrid offline and online 'meetup' communities". Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice. 8 (1): 46–57. doi:10.1057/palgrave.dddmp.4340552.

- Toledano, Margalit (2017). "Emergent methods: Using netnography in public relations research". Public Relations Review. 43 (3): 597–604. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.03.007. ISSN 0363-8111.

- Vynck, Gerrit De (November 28, 2017). "WeWork Buys Meetup to Bring People Together Outside of Work". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Zhang, Shuo; Lv, Qin (2018). "Hybrid EGU-based group event participation prediction in event-based social networks". Knowledge-Based Systems. 143: 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2017.12.002. ISSN 0950-7051.