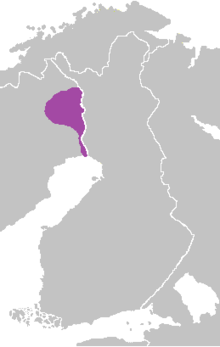

Meänkieli dialects

Meänkieli (literally "our language") is a Finnic language spoken in the northernmost part of Sweden along the valley of the Torne River. Its status as an independent language is disputed but in Sweden it is recognized as one of the country's five minority languages.

| Meänkieli | |

|---|---|

| meänkieli | |

| Native to | Sweden, Finland |

| Region | Torne Valley |

Native speakers | 60,000 (1997–2009)[1] |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | fit |

| Glottolog | torn1244[2] |

Linguistically, Meänkieli consists of two dialect subgroups, the Torne Valley dialects (also spoken on the Finnish side of the Torne River) and the Gällivare dialects, which both belong to the larger Peräpohjola dialect group (see Dialect chart).[3] For historical and political reasons it has the status of a minority language in Sweden. In modern Swedish the language is normally referred to officially as meänkieli, although colloquially an older name, tornedalsfinska ("Torne Valley Finnish"), is still commonly used. Sveriges Radio tends to use tornedalsfinska for the culture generally and meänkieli specifically for the language.[4]

Meänkieli is distinguished from Standard Finnish by the absence of 19th- and 20th-century developments in Finnish.[5] Meänkieli also contains many loanwords from Swedish and Sámi pertaining to daily life. However, the frequency of loanwords is not exceptionally high when compared to some other Finnish dialects: for example, the dialect of Rauma has roughly as many loanwords from Swedish but Meänkieli also contains a few Sámi loanwords and words that have died out from the Finnish language but were retained in Meänkieli due to isolation from the Finnish language. Meänkieli lacks two of the grammatical cases used in Standard Finnish, the comitative and the instructive (they are used mostly in literary, official language in Finland). And the verb conjugations of Meänkieli are different than in Finland. There is also a dialect of Meänkieli spoken around Gällivare that differs even more from Standard Finnish. Meänkieli also has a few words that are not found in either Swedish, Standard Finnish or Sami, for example "porista" (to talk), "son" (it is) and "sole" (it is not).[6]

History

Before 1809, all of what is today Finland was an integral part of Sweden. The language border went west of the Torne Valley area, so a small part of today's Sweden, along the modern border, was historically Finnish speaking (just like most areas along the eastern coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, areas that were ceded to Russia and are part of modern Finland, were historically Swedish speaking, and to a large extent still are). The area where Meänkieli is spoken that is now Finnish territory (apart from the linguistically Sami and Swedish parts of this geographical area), formed a dialect continuum within the Realm of Sweden. Since the area east of Torne River was ceded to Russia in 1809, the language developed in partial isolation from standard Finnish. In 1826 the state Church of Sweden appointed the priest and amateur botanist Lars Levi Laestadius to be the Vicar over the Karesuando parish, which is situated along the Muonio River north of the Arctic Circle on the border of Finland in Swedish Lapland. The population of Karesuando was predominantly Finnish-speaking people of Sami, Finnish, and Swedish mixed descent. Laestadius reported that the local dialect was notably different from standard Finnish, though he did not give it a name.

In the 1880s, the Swedish state decided that all citizens of the country should speak Swedish. Part of the reason was military; people close to the border speaking the language of the neighbouring country rather than the major language in their own country might not be trusted in case of war. Another reason was that Finns were regarded as being of another "race." The official Swedish opinion was that "the Sami and the Finnish tribes belong[ed] more closely to Russia than to Scandinavia".[7] Beginning around this time, the schools in the area only taught in Swedish, and children were forbidden under penalty of physical punishment from speaking their own language at school even during class breaks. Native Meänkieli speakers were prevented by the authorities from learning Standard Finnish as a school subject for decades, which resulted in the survival of the language only in oral form.

Meänkieli today

On April 1, 2000, Meänkieli became one of the now five nationally recognized minority languages of Sweden, which means it can be used for some communication with local and regional authorities in the communities along the Finnish border. Its minority language status applies in designated local communities and areas, not throughout Sweden.

Few people today speak Meänkieli as their only language, with speakers usually knowing Swedish and often standard Finnish as well. Estimates of how many people speak Meänkieli vary from 30,000 to 70,000, of whom most live in Norrbotten. Many people in the northern parts of Sweden understand some Meänkieli, but fewer people speak it regularly. People with Meänkieli roots are often referred to as Tornedalians although the Finnish-speaking part of Norrbotten is a far larger area than the Torne River Valley; judging by the names of towns and places, the Finnish-speaking part of Norrbotten stretches as far west as the city of Gällivare.

Today Meänkieli is declining. Few young people speak Meänkieli as part of daily life though many have passive knowledge of the language from family use, and it is not uncommon for younger people from Meänkieli-speaking families to be more familiar with standard Finnish, for which literature, radio, TV and courses are much more readily available. The language is taught at Stockholm University, Luleå University of Technology, and Umeå University. Bengt Pohjanen is a trilingual author from the Torne Valley. In 1985 he wrote the first Meänkieli novel, Lyykeri. He has also written several novels, dramas, grammars, songs and films in Meänkieli.

The author Mikael Niemi's novels and a film based on one of his books in Swedish have improved awareness of this minority among Swedes. Since the 1980s, people who speak Meänkieli have become more aware of the importance of the language as a marker of identity. Today there are grammar books, a Bible translation, drama performances, and there are some TV programmes in Meänkieli.

On radio, programmes in Meänkieli are broadcast regularly from regional station P4 Norrbotten (as well as local station P6 in Stockholm) on Mondays to Thursdays between 17:10 and 18:00, while on Sundays further programmes are carried by P6 between 8:34 and 10:00 (also on P2 nationwide from 8:34 to 9:00). All of these programmes are also available via the Internet.

Comparison of an example of Meänkieli and Standard Finnish

| Meänkieli[8] | Finnish | |

|---|---|---|

| Ruotti oon demokratia. Sana demokratia | Ruotsi on demokratia. Sana demokratia | |

| tarkottaa kansanvaltaa. Se merkittee | tarkoittaa kansanvaltaa. Se merkitsee, | |

| ette ihmiset Ruottissa saavat olla matkassa | että ihmiset Ruotsissa saavat olla mukana | |

| päättämässä miten Ruottia pittää johtaa. | päättämässä, miten Ruotsia pitää johtaa. | |

| Meän perustuslaissa sanothaan ette kaikki | Meidän perustuslaissamme sanotaan, että kaikki | |

| valta Ruottissa lähtee ihmisistä ja ette | valta Ruotsissa lähtee ihmisistä ja että | |

| valtiopäivät oon kansan tärkein eustaja. | valtiopäivät ovat kansan tärkein edustaja. | |

| Joka neljäs vuosi kansa valittee kukka | Joka neljäs vuosi kansa valitsee, ketkä | |

| heitä eustavat valtiopäivilä, maakäräjillä | heitä edustavat valtiopäivillä, maakäräjillä | |

| ja kunnissa. | ja kunnissa. |

Literal English translation:

Sweden is a democracy. The word democracy means rule by the people. It means that people in Sweden are allowed to participate in deciding how Sweden is to be governed. It is said in our constitution that all power in Sweden comes from the people and that the Riksdag is the most important representative of the people. Every four years the people choose those who will represent them in the Riksdag, county councils, and municipalities. Example 2[9]

| Meänkieli | Finnish |

|---|---|

| Hallitus oon epäonnistunnu osittain heän minuriteettipulitiikassa

Issoin osa kunnista ja maakärajistä ei tehe aktiiivista työtä perussuojan kans johonka minuriteettikansala oon oikeus. |

Hallitus on epäonnistunut osittain vähemmistöpolitiikassaan.

Suurin osa kunnista ja maakäräjistä ei toimi riittävän aktiivisesti turvatakseen perussuojan, johon vähemmistökansalla on oikeus. |

| Silti tutkimus, jonka Lennart Rohdin oon allekirjottannu, esittää korjaamista.

Esimerkiksi häätyy liittää minuriteettikysymykset Koululakhiin ja Sosiaalipalvelulakhiin ette net saava suureman merkityksen. Vasittu kielikeskus meänkielele saatethaan kans panna etusiale. |

Siksi selvitys, jonka Lennart Rohdin on allekirjoittanut, esittää toimenpiteitä.

Muun muassa vähemmistökysymykset pitää sisällyttää koululakiin ja sosiaalipalvelulakiin, jotta ne voitaisiin ottaa riittävästi huomioon. Erityinen kielikeskus meänkielelle voidaan myös asettaa etusijalle. |

Dialect or a language?

The reason there is a debate is because the line between a dialect and a language is not clear. Meänkieli received the status of a separate language in Sweden for political, historical and sociological reasons. Linguistically it can be grouped into the northern dialects of Finnish and the difference between northern Finnish dialects in Meänkieli is the loanword count. Meänkieli has about the same amount of Swedish loanwords as the dialect of Rauma but Meänkieli also has Sami loanwords but they are less common.[10] People who claim that it is a language usually point to the literary scene of Meänkieli and that it has its own separate literary language. also sociological, political and historical reasons while the people who claim it is a dialect use a more conservative way of pure linguistics.[11] Meänkieli is very similar to the northern dialects of Finnish but due to not having been effected by the literary language of Finland it has kept many elements that have died in Finnish and has adopted many Swedish loanwords. Currently the status of Meänkieli is very debatable but it has been developing in a different direction than Finnish.[12]

Some Meänkieli words not used in standard Finnish

- äpyli = apple(s)

- son/s´oon = it is

- sole = it is not

- klaarata = to get along(s)

- sturaani = ugly

- potati = potato(s)

- pruukata = to have a habit of

- följy = along with, company(s)

- ko = when, as, since

- fiskata = to fish(s)

- kläppi = child

- muuruutti = carrot(s)

- porista = to talk

- praatata = to speak(s)

- kahveli = fork(s)

- pruuvata = to try(s)

- kniivi = knife(s)

- knakata = to knock(s)

- öölata = to drink alcohol(s)

- miilu = game

- knapsu = feminine man

- fruukosti = breakfast(s)

- fältti = field(s)

- funteerata = to think(s)

- engelska = English(s)

- fryysbuksi = freezer(s)

- flakku = flag(s)

- häätyy = to have to

(s)=Borrowed from Swedish

Example of Sámi loanwords in Meänkieli

- kobbo = hill

- kiena = slope

- veiki = dark time

- suohka = porridge

- roina = skinny

- muijula = to smile

- kaanij = ghost

- jutu = route[13]

Differences between Finnish and Meänkieli

In many situations where Finnish has "v", Meänkieli has "f"

- färi = väri "color"

- fuori = vuori "mountain"

- fankila = vankila "prison"

Some loanwords with "y" in Meänkieli have "u" in Finnish

- kylttyyri = kulttuuri "culture"

- resyrssi = resurssi "resource"

In some loanwords "o" in Finnish corresponds to "u" in Meänkieli

- puliisi = poliisi "police"

- pulitiikka = politiikka "politics"

In some loanwords "d" in Finnish corresponds to "t" in Meänkieli

- tynamiitti = dynamiitti "dynamite"

Standard Finnish "d" has disappeared in some places

- tehä = tehdä "to make"

- meän = meidän "our"

- heän = heidän "their"

Double consonants

References

- Meänkieli at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Tornedalen Finnish". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sveriges Radio press release 22.02.2017 (in Swedish)

- "Meänkieli, yksi Ruotsin vähemmistökielistä - Kielikello". www.kielikello.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- "Meänkielen sanakirja". meankielensanakirja.com. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- L.W.A Douglas, Hur vi förlorade Norrland – How We Lost Norrland, Stockholm 1889, p.17

- Tervetuloa valtiopäivitten webbsivuile meänkielelä!. Accessed 2009-02-10

- "Kielikeskus meänkielele ja uusi virasto pelastaa epäonnistunheen minuriteettipulitiikan – STR-T" (in Finnish). Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- "Murre vai kieli - M.A. Castrénin seura". www.ugri.net. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "Meänkieli, yksi Ruotsin vähemmistökielistä - Kielikello". www.kielikello.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "Meänkieli, yksi Ruotsin vähemmistökielistä - Kielikello". www.kielikello.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- "Meänkielen sanakirja". meankielensanakirja.com. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "Meänkielen sanakirja". meankielensanakirja.com. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- "Meänkieli", Wikipedia (in Finnish), 2020-01-20, retrieved 2020-01-26

External links

| Meänkieli dialects test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- MeänViesti

- Torniolaaksolaiset

- Pohjankielet

- Ridanpää, Juha (2018) Why save a minority language? Meänkieli and rationales of language revitalization. - Fennia : International Journal of Geography 169 (2), 187-203.