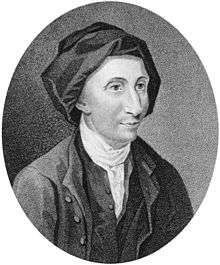

Matthew Maty

Matthew Maty (17 May 1718 – 2 July 1776), originally Matthieu Maty, was a Dutch physician and writer of Huguenot background, and after migration to England secretary of the Royal Society and the second principal librarian of the British Museum.

Early life

The son of Paul Maty, he was born at Montfoort, near Utrecht, the Netherlands, on 17 May 1718. His father was a Protestant refugee from Beaufort, Provence; he settled in the Dutch Republic and became minister of the Walloon church at Montfoort, and subsequently catechist at The Hague, but was dismissed from his benefices and excommunicated by synods at Kampen and The Hague in 1730 for maintaining, in a letter on ‘The Mystery of the Trinity’ to De la Chappelle, that the Son and Holy Spirit are two finite beings created by God, and at a certain time united to him. After ineffectual protest against the decision of the synods, the elder Maty sought refuge in England, but was unable to find patronage there, and had to return to The Hague, whence his enemies drove him to Leiden. He lived in Leiden with his brother Charles Maty, compiler of a Dictionnaire géographique universel (1701 and 1723, Amsterdam), in 1751, being then seventy years of age. He subsequently returned to England, and lived with his son in London, where he died on 21 March 1773.

Matthew was entered at Leiden University on 31 March 1732, and graduated PhD in 1740, the subject for his inaugural dissertation (which shows Montesquieu's influence) being ‘Custom.’ A French version of the Latin original, greatly modified, appeared at Utrecht in 1741 under the title ‘Essai sur l'Usage,’ and attracted some attention. He also graduated M.D. at Leiden, 11 February 1740, with a parallel dissertation, ‘De Consuetudinis Efficacia in Corpus Humanum.’

In England

In 1741, he came over to London, England, and set up in practice as a physician. He frequented a club which numbered Drs James Parsons, Peter Templeman, William Watson, and John Fothergill among its members, and met every fortnight in St Paul's Churchyard, but soon began to devote his energies to literature. He began in 1750 the publication of the bi-monthly Journal Britannique, which was printed at the Hague, and gave an account in French of the chief productions of the English press. The ‘Journal,’ which had a considerable circulation in the Low Countries, on the Rhine, and at Paris, Geneva, Venice, and Rome, as well as in England, became in Maty's hands an instrument of eulogy; and it continued to illustrate, in Edward Gibbon's words, ‘the taste, the knowledge, and the judgment of Maty’ until December 1755, by which time it had introduced him to a wide circle of literary friends.

He had been elected Fellow of the Royal Society on 19 December 1751, and in 1753, on the establishment of the British Museum, he was nominated, together with James Empson, an under-librarian, the appointment being confirmed in June 1756. Gibbon described Maty as one of the last disciples of the school of Fontenelle, and revised his Essai sur l'étude de la littérature in accordance with Maty's advice; nervous that his French, acquired in Lausanne, might appear provincial rather than Parisian, Gibbon had come hoping for a rather stronger endorsement than Maty's introduction to the work turned out to be.[1] Maty was, though, on bad terms with Samuel Johnson after some comments in his 'Journal'; when his name was mentioned in 1756 by Dr William Adams as a suitable assistant in the projected review of literature, Johnson's sole comment was, ‘The little black dog! I'd throw him into the Thames first.’ He was in frequent intercourse with Hans Sloane and other scientific men, was an advocate of inoculation, and against doubts of its efficacy experimented on himself.

On 1 March 1760, he unsuccessfully applied to the Duke of Newcastle for the post of secretary to the Society of Arts; but he was in March 1762 elected foreign secretary of the Royal Society, in succession to Dr James Parsons. He was at this time member of a literary society which included John Jortin, Wetstein, Ralph Heathcote, De Missy, and Thomas Birch. On the resignation of the post by Birch (who died a few months later and left him his executor), Maty was, 30 November 1765, appointed secretary of the Royal Society. He was in the same year admitted a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians.

In 1772, on the death of Gowin Knight, Maty was nominated his successor as principal librarian of the British Museum. In his capacity as chief librarian he placed, like his predecessor, difficulties in the way of visitors. He bought a number of valuable books for the Museum at Anthony Askew's sale in 1775. Maty died on 2 July 1776. His books were sold in 1777 by Benjamin White.

Works

Maty's chief works are:

- Ode sur la Rebellion en Écosse, Amsterdam, 1746.

- Essai sur le Caractère du Grand Medecin, ou Eloge Critique de Mr. Herman Boerhaave, Cologne, 1747.

- Authentic Memoirs of the Life of Richard Mead, M.D., London, 1755, expanded from a memoir in the ‘Journal Britannique.’

His contributions to the Philosophical Transactions are enumerated in Robert Watt's Biblioteca Britannica. He completed for the press Thomas Birch's Life of John Ward, published in 1766, and translated from the French A Discourse on Inoculation, read before the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, 24 April 1754, by Mr. La Condamine, with a preface, postscript, and notes, 1765, and New Observations on Inoculation, by Dr. Garth, Professor of Medicine at Paris, 1768.

At the time of his death Maty had nearly finished the Memoirs of the Earl of Chesterfield, work assisted by Solomon Dayrolles,[2] which were completed by his son-in-law Justamond, and prefixed to the Miscellaneous Works, 2 vols., 1777 of Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield. Maty had been one of Chesterfield's executors.

Family

He was twice married: first to Elizabeth Boisragon, by whom he had a son Paul Henry Maty, and three daughters, of whom Louisa (died 1809) married Rogers (1732–1795), only son of John Jortin, and Elizabeth married John Obadiah Justamond, F.R.S., surgeon of Westminster Hospital, and translator of Abbé Raynal's ‘History of the East and West Indies,’ and secondly to Mary Deners.

References

- J. G. A. Pocock, Barbarism and Religion, vol. 1: The Enlightenments of Edward Gibbon, 1737–1764 (1999), p. 242.

- Dictionary of National Biography, article on Dayrolles.

- Attribution

![]()

Further reading

- Uta Janssens (1975), Matthieu Maty and the Journal Britannique 1750–1755: A French view of English literature in the middle of the 18th century.

- Uta Janssens, Matthieu Maty and the adoption of inoculation for smallpox in Holland, Bull. Hist. Med. 1981 Summer; 55(2):246–56.

External links