Mary Sidney

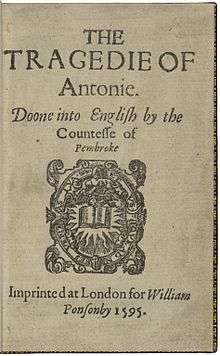

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (née Sidney; 27 October 1561 – 25 September 1621) was one of the first English women to achieve a major reputation for her poetry and literary patronage. By the age of 39, she was listed with her brother Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser and William Shakespeare as one of the notable authors of her time in the verse miscellany, Belvidere, by John Bodenham.[1] The influence of her play Antonius is widely recognized; it stimulated a revived interest in the soliloquy based on classical models and was a likely source, among others, for both the closet drama Cleopatra (1594) by Samuel Daniel and Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra (1607).[upper-alpha 1] Sidney was also known for her translation of Petrarch's "Triumph of Death," from the poetry anthology Triumphs, but it is her lyric translation of the Psalms that has secured her poetic reputation.

Mary Sidney Herbert | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Mary Herbert née Sidney, by Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1590 | |

| Born | 27 October 1561 Tickenhill Palace, Bewdley, Worcs, England |

| Died | 25 September 1621 Aldersgate Street, London, England |

| Burial place | Salisbury Cathedral |

| Known for | Literary patron, author |

| Title | Countess of Pembroke |

| Spouse(s) | Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

Biography

Early life

Mary Sidney was born on 27 October 1561 at Tickenhill Palace in the parish of Bewdley, Worcestershire.[2] She was one of the seven children – three sons and four daughters – of Sir Henry Sidney and wife Mary Dudley. Their eldest son was Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586),[3] and their second son Robert Sidney (1563–1626), who later became Earl of Leicester. As a child, she spent much time at court where her mother was a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber and a close confidante of Queen Elizabeth I.[4] Like her brother Philip, she received a humanist education which included music, needlework, and classical languages like French and Italian. Following the death of Sidney's youngest sister, Ambrosia, in 1575, the queen requested that Mary to return to court to join the royal entourage.[2]

Marriage and children

In 1577, Mary Sidney married Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1538–1601), a close ally of the family. The marriage was arranged by her father, and uncle Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. As countess of Pembroke, Mary was responsible for a number of estates including Ramsbury, Ivychurch,[5] Wilton House, and Baynard's Castle in London, where it is known that they entertained Queen Elizabeth to dinner. She had four children by her husband:

- William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1580–1630), was the eldest son and heir.

- Katherine Herbert (1581–1584)[6] died as an infant.

- Anne Herbert (born 1583 – after 1603) was speculated also to have been a writer and a storyteller.[6]

- Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke (1584–1650), succeeded his brother in 1630. Philip and his older brother William were the "incomparable pair of brethren" to whom the First Folio of Shakespeare's collected works was dedicated in 1623.

Mary Sidney was also aunt to the poet Mary Wroth, the daughter of her brother Robert.

Later life

Sidney's husband died in 1601. His death left her with less financial support than she might have expected, though views on its adequacy vary; at the time the majority of an estate was left to the eldest son.

In addition to the arts, Sidney had a range of interests. She had a chemistry laboratory at Wilton House, where she developed medicines and invisible ink.[7] From 1609 to 1615, Mary Sidney probably spent most of her time at Crosby Hall in London. She travelled with her doctor, Sir Matthew Lister, to Spa, Belgium. There is conjecture that she married Lister, but there is no evidence of this.[8]

She died of smallpox on 25 September 1621, aged 59, at her townhouse in Aldersgate Street in London, shortly after King James I had visited her at the newly completed Houghton House in Bedfordshire.[2] After a grand funeral in St Paul's Cathedral, her body was buried in Salisbury Cathedral, next to that of her late husband in the Herbert family vault, under the steps leading to the choir stalls, where the mural monument still stands.[2]

Literary career

Wilton House

Mary Sidney turned Wilton House into a "paradise for poets", known as the "Wilton Circle," a salon-type literary group sustained by her hospitality, which included Edmund Spenser, Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, Ben Jonson, and Sir John Davies. John Aubrey wrote, "Wilton House was like a college, there were so many learned and ingenious persons. She was the greatest patroness of wit and learning of any lady in her time."[9] Sidney received more dedications than any other woman of non-royal status.[10] By some accounts, King James I visited Wilton on his way to his coronation in 1603 and stayed again at Wilton following the coronation to avoid the plague. She was regarded as a muse by Daniel in his poem "Delia", an anagram for ideal.[11]

Her brother, Philip Sidney, wrote much of his Arcadia in her presence, at Wilton House. He also likely began preparing his English lyric version of the Book of Psalms at Wilton as well.

Sidney psalter

Philip Sidney had completed 43 of the 150 Psalms at the time of his death during a military campaign against the Spanish, in the Netherlands in 1586. She finished his translation of the psalms, composing Psalms 44 through 150 in a dazzling array of verse forms, using the 1560 Geneva Bible and commentaries by John Calvin and Theodore Beza. Hallett Smith has called the psalter a "School of English Versification" Smith (1946), of one hundred and seventy-one poems (Psalm 119 is a gathering of twenty-two separate poems). A copy of the completed psalter was prepared for Queen Elizabeth I in 1599, in anticipation of a royal visit to Wilton, but Elizabeth cancelled her planned visit. This work is usually referred to as "The Sidney Psalms" or "The Sidney-Pembroke Psalter" and is regarded as an important influence on the development of English religious lyric poetry in the late 16th and early 17th century.[12] John Donne wrote a poem celebrating the verse psalter and claiming that he could "scarce" call the English Church reformed until its psalter had been modelled after the poetic transcriptions of Philip Sidney and Mary Herbert.[13]

Although the psalms were not printed in her lifetime, they had extensive manuscript publication. There are 17 extant manuscripts today. A later engraving of Herbert shows her holding them.[15] Her literary influence can be seen through literary patronage, through publishing her brother's works and through her own verse forms, dramas, and translations. Contemporary poets who commended Herbert's verse psalms include Samuel Daniel, Sir John Davies, John Donne, Michael Drayton, Sir John Harington, Ben Jonson, Aemelia Lanyer, and Thomas Moffet.[10] The importance and influence of the Psalter translation is evident in the devotional lyric poems of Barnabe Barnes, Nicholas Breton, Henry Constable, Francis Davison, Giles Fletcher, and Abraham Fraunce — and its influence upon the later religious poetry of Donne, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, and John Milton has been critically recognized since Louis Martz placed it at the start of a developing tradition of seventeenth-century devotional lyric.[2]

Sidney was instrumental in having her brother's An Apology for Poetry or Defence of Poesy, put into print, and she circulated the "Sidney–Pembroke Psalter" in manuscript at about the same time. The simultaneity suggests a proximate relationship in their design: both argued, in formally different ways, for the ethical recuperation of poetry as an instrument for moral instruction — particularly for religious instruction.[16] Sidney also took on the editing and publishing her brother's Arcadia, which he claims to have written in her presence as The Countesse of Pembroke's Arcadia.[17]

Other works

Sydney's closet drama Antonius is a translation of a French play, Marc-Antoine (1578) by Robert Garnier. Mary is known to have translated two other works: A Discourse of Life and Death by Philippe de Mornay, which was published with Antonius in 1592, and Petrarch's The Triumph of Death, which was circulated in manuscript. Her original poems include the pastoral, "A Dialogue betweene Two Shepheards, Thenot and Piers, in praise of Astrea,"[18] and two dedicatory addresses, one to Elizabeth I and one to her brother Philip, contained in the Tixall manuscript copy of her verse psalter. An elegy for Philip, The dolefull lay of Clorinda, which was published in Colin Clouts Come Home Againe (1595), has been attributed to Spenser and to Mary Herbert, but Pamela Coren is probably right in awarding it to Spenser, and certainly right to say that Mary's poetic reputation does not suffer from loss of the attribution.Coren (2002)

By at least 1591, the Pembrokes were providing patronage to the Pembroke's Men playing company, one of the early companies to perform the works of Shakespeare. According to one account Shakespeare's company "The King's Men" performed at Wilton at this time.[19]

June and Paul Schlueter published an article in The Times Literary Supplement of 23 July 2010, in which they described a manuscript of newly discovered works by Mary Sidney Herbert.[20]

Connection with Shakespeare

There has been speculation that she wrote Shakespeare's sonnets. Robin P. Williams presents a circumstantial case that Mary Sidney might have written the sonnets attributed to Shakespeare, 17 of them urging her brother to marry and most of the others to her lover, Dr Mathew Lister. Williams also sees the Lister relationship behind the play All's Well That Ends Well. Williams acknowledges that there is no documentary evidence for the case, but notes that the detailed knowledge shown in the plays of sailing, archery, falconry, alchemy, astronomy, cooking, medicine and travel correlate with what we know of Mary Sidney's life and interests.[7]

Her poetic epitaph, ascribed to Ben Jonson but more likely to have been written in an earlier form by the poets William Browne and her son William, summarizes how she was regarded in her own day:[2]

Underneath this sable hearse,

Lies the subject of all verse,

Sidney's sister, Pembroke's mother.

Death, ere thou hast slain another

Fair and learned and good as she,

Time shall throw a dart at thee.

Related pages

Notes

- Both dramas portray the lovers as "heroic victims of their own passionate excesses and remorseless destiny" Shakespeare (1990, p. 7)

References

- Bodenham 1911.

- ODNB 2008.

- ODNB 2014.

- ODNB 2008b.

- Pugh & Crittall 1956, pp. 289–295.

- Hannay, Kinnamon & Brennan 1998, pp. 1–93.

- Williams 2006.

- Britain Magazine 2017.

- Aubrey & Barber 1982.

- Williams 1962.

- Daniel 1592.

- Martz 1962.

- Donne 1599, contained in Chambers (1896).

- Walpole 1806.

- Mary Herbert as illustrated in Horace Walpole, A Catalogue of the Royal and Noble Authors of England, Scotland, and Ireland.[14]

- Coles 2012.

- Sidney 1590.

- Herbert 1599.

- Halliday 1977, p. 531.

- Schlueter & Schlueter 2010.

Sources

- Adams, Simon (2008b) [2004], "Sidney [née Dudley], Mary, Lady Sidney", ODNB, OUP, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69749 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Aubrey, John; Barber, Richard W (1982). Brief Lives. Boydell. ISBN 9780851152066.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bodenham, John (1911) [1600]. Hoops, Johannes; Crawford, Charles (eds.). Belvidere, or the Garden of the Muses. Liepzig. pp. 198–228.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Britain Magazine, Natasha Foges (2017). "Mary Sidney: Countess of Pembroke and literary trailblazer".CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever, ed. (1896). The Poems of John Donne. Introduction by George Saintsbury. Lawrence & Bullen/Routledge. pp. 188–190.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coles, Kimberly Anne (2012). "Mary (Sidney) Herbert, countess of Pembroke". In Sullivan, Garrett A; Stewart, Alan; Lemon, Rebecca; McDowell, Nicholas; Richard, Jennifer (eds.). The Encyclopedia of English Renaissance Literature. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405194495.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coren, Pamela (2002). "Colin Clouts come home againe | Edmund Spenser, Mary Sidney, and the doleful lay". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 42 (1): 25–41. doi:10.1353/sel.2002.0003. ISSN 1522-9270.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daniel, Samuel (1592). "Delia".CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donne, John (1599) [1952]. "Upon the translation of the Psalmes by Sir Philip Sidney, and the Countesse of Pembroke his Sister". In Gardner, Helen (ed.). Divine Poems | Occassional Poems. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780198118367.book.1. ISBN 978-0198118367.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) [sic]

- Halliday, Frank Ernest (1977). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Penguin/Duckworth. ISBN 978-0715603093.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hannay, Margaret; Kinnamon, Noel J; Brennan, Michael, eds. (1998). The Collected Works of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke. I: Poems, Translations, and Correspondence. Clarendon. ISBN 978-0198112808. OCLC 37213729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hannay, Margaret Patterson (2008) [2004], "Herbert [née Sidney], Mary, countess of Pembroke", ODNB, OUP, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13040 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Herbert, Mary (2014) [1599]. "A dialogue betweene two shepheards, Thenot and Piers, in praise of Astrea". In Goldring, Elizabeth; Eales, Faith; Clarke, Elizabeth; Archer, Jayne Elisabeth; Heaton, Gabriel; Knight, Sarah (eds.). John Nichols's The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth I: A New Edition of the Early Modern Sources. 4: 1596–1603. Produced by John Nichols and Richard Gough (1788). OUP. doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00058002. ISBN 978-0199551415.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lafayette College, Schlueter & Schlueter (23 Sep 2010). "June and Paul Schlueter Discover Unknown Poems by Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke".CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martz, Louis L (1954). The poetry of meditation: a study in English religious literature of the seventeenth century (2nd ed.). Yale UP. ISBN 978-0300001655. OCLC 17701003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pugh, R B; Crittall, E, eds. (1956). "Houses of Augustinian canons: Priory of Ivychurch". A History of the County of Wiltshire. Volume III.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shakespeare, William (1990) [1607]. Bevington, David M (ed.). Antony and Cleopatra. CUP. ISBN 978-0521272506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sidney, Philip (2003) [1590 published by William Ponsonby]. The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. Transcriptions: Heinrich Oskar Sommer (1891); Risa Stephanie Bear (2003). Renascence Editions, Oregon U.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Hallett (1946). "English Metrical Psalms in the Sixteenth Century and Their Literary Significance". Huntington Library Quarterly. 9 (3): 249–271. doi:10.2307/3816008. JSTOR 3816008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walpole, Horatio (1806). "Mary, Countess of Pembroke". A Catalogue of the Royal and Noble Authors of England, Scotland and Ireland; with Lists of Their Works. II. Enlarged and continued — Thomas Park. J Scott. pp. 198–207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Franklin B (1962). The literary patronesses of Renaissance England. Notes and Queries. 9. pp. 364–366. doi:10.1093/nq/9-10-364b.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Robin P (2006). Sweet Swan of Avon: Did a woman write Shakespeare?. Peachpit. ISBN 978-0321426406.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woudhuysen, H R (2014) [2004], "Sidney, Sir Philip", ODNB, OUP, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25522 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Clarke, Danielle (1997). "'Lover's songs shall turne to holy psalmes': Mary Sidney and the transformation of Petrarch". Modern Language Review. MHRA. 92 (2): 282–294. doi:10.2307/3734802. JSTOR 3734802.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coles, Kimberly Anne (2008). Religion, reform, and women's writing in early modern England. CUP. ISBN 978-0521880671.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodrich, Jaime (2013). Faithful Translators: Authorship, Gender, and Religion in Early Modern England. Northwestern UP. ISBN 978-0810129696.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamlin, Hannibal (2004). Psalm culture and early modern English literature. CUP. ISBN 978-0521037068.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hannay, Margaret P (1990). Philip's phoenix: Mary Sidney, countess of Pembroke. OUP. ISBN 978-0195057799.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamb, Mary Ellen (1990). Gender and authorship in the Sidney circle. Wisconsin UP. ISBN 978-0299126940.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prescott, Anne Lake (2002). "Mary Sidney's Antonius and the ambiguities of French history". Yearbook of English Studies. MHRA. 38: 216–233.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quitslund, Beth (2005). "Teaching us how to sing? The peculiarity of the Sidney psalter". Sidney Journal. Faculty of English, U Cambridge. 23 (1–2): 83–110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rathmell, J C A, ed. (1963). The psalms of Sir Philip Sidney and the countess of Pembroke. New York UP. ISBN 978-0814703861.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rienstra, Debra; Kinnamon, Noel (2002). "Circulating the Sidney–Pembroke psalter". In Justice, George L; Tinker, Nathan (eds.). Women's writing and the circulation of ideas: manuscript publication in England, 1550–1800. CUP. pp. 50–72. ISBN 978-0521808569.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trill, Suzanne (2010). "'In poesie the mirrois of our age': the countess of Pembroke's 'Sydnean' poetics". In Cartwright, Kent (ed.). A companion to Tudor literature. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 428–443. ISBN 978-1405154772.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Micheline (2005). "Protestant Women's Writing and Congregational Psalm Singing: from the Song of the Exiled "Handmaid" (1555) to the Countess of Pembroke's Psalmes (1599)". Sidney Journal. Faculty of English, U Cambridge. 23 (1–2): 61–82.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mary Sidney Herbert. |

- Works by Mary Sidney at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mary Sidney at Internet Archive

- "The Works of Mary (Sidney) Herbert" (for some of the original texts and Psalms), luminarium.org; accessed 27 March 2014.

- Project Continua: Biography of Mary Sidney